SPACE December 2025 (No. 697)

©Park Heejun

Living Together Again

Herein is the story of a large extended family centred around a strong woman. The client – at once simultaneously a daughter, daughter-in-law, and mother – has taken on the entire responsibilities of planning, coordinating, and communicating the design of a house that will accommodate more than ten people: her own parents, her mother-in-law, the client couple, their three children, and an additional rental unit. Speaking with her felt like talking to a neighbourhood community leader. The process of gathering and reconciling the opinions and registering the needs of each generation resembled the supervision of an alleyway community. Around her, the reality of the house began to take shape.

For three generations to live together again requires a design of careful negotiation—one that addresses individual conditions while also creating an architecture for a new kind of community, one that goes beyond the primitive family structure assumed by modern society. The project reconsiders the meaning of the individual and the family, concepts long taken for granted in the modern era, and seeks forms shaped by the new relationships required of today’s world.

A house may be in private ownership, but the moment it enters a neighbourhood it becomes an integral part of it. I approached the house as a small building that is, at the same time, urban; an aggregation of individuals that is, simultaneously, social.

Like a Folk House

The site is located within a region where mountains and streams, old villages with small-scale houses, and vegetable gardens, as well as a new town made up of large apartment complexes and commercial buildings, coexist. The surrounding houses cultivate gardens of various size, storing farming tools and household items under its eaves, hanging laundry and daily goods along its outdoor stairs. Such scenes from everyday life define what might be called an ‘urban folk dwelling’, presenting a landscape in stark contrast to that of apartment complexes. In this threshold between the two, we hoped our design would embody the richness and warmth of a traditional village home.

(left) Site plan drawing, (right) Section perspective

The Power of Surviving Land

The site takes a narrow and long triangular shape—a fragment that seems as if it has been cut out from the city. We speculate that this site survived as a leftover piece of land—first set apart from the grid-patterned housing development to its east long ago and later from the large-scale apartment development to its west. It is almost as if the site itself is a gap in the city’s urban development plans, an untouched area that has escaped the taint of human hands. A neighbouring house, with its large, old roof, appears to be one of the oldest in the area preserving the original shape of the site. Meanwhile, the road at the front of the site is newly developed and has influenced the present form.

Therefore, we explored ways by which the site’s unique shape and charm could permeate not only the exterior spaces but the whole building, inside and out. Rather than merely deciding whether to fill or empty elements of the site, we wanted to let the architecture respond to the lines of the land, allowing the energy of the site itself to flow into the building.

Collective Houses

If there is a design approach which aims to maximise the floor area by filling the site completely and shaping the mass according to regulations, this house instead takes the form of multiple small houses gathered together. On the triangular site, the small houses overlap and offset each other slightly, each recognised as an individual entity and as part of a whole. Meanwhile, the house opens outward toward the neighbourhood. The small courtyard on the ground level serves as the entrance to the rental unit of the second floor, while for the third floor, it becomes a terrace open on two sides. These slightly shifted and loosely connected houses facing each other maintain a distance that makes you feel as if you are looking at a stranger when observing oneself.

The intuitive form where multiple parts come together to create a whole—offers its inhabitants a diverse palette of spatial experiences. Rather than a feeling of dividing a single house, it radiates a sense of having individual homes that are interlinked. The three volumes, with their roofs overlapping, create the image of a collective cluster. This is not a single, complete object but an organised, communal work of architecture. Like neighbouring homes gathered closely together, this house aspires to be the kind of architecture that is part of a small village or city—a collective, communal dwelling.

Dynamic Architecture

A cluster of small houses gathered together lends movement to architecture. Architecture is, by nature, a fixed entity—but what happens when we infuse it with a sense of motion? It then radiates a sensation somewhere between the stable and the movable, as of an organism in still-motion. When we look at a photograph of a running cheetah, we can imagine its motion even though the image is frozen. What if a still building could also possess this invisible yet palpable vitality? Though architecture itself is static and it is only the people inside it that are mobile, could a building not serve as both the setting and the expressive backdrop for the diverse movements and lives unfolding within?

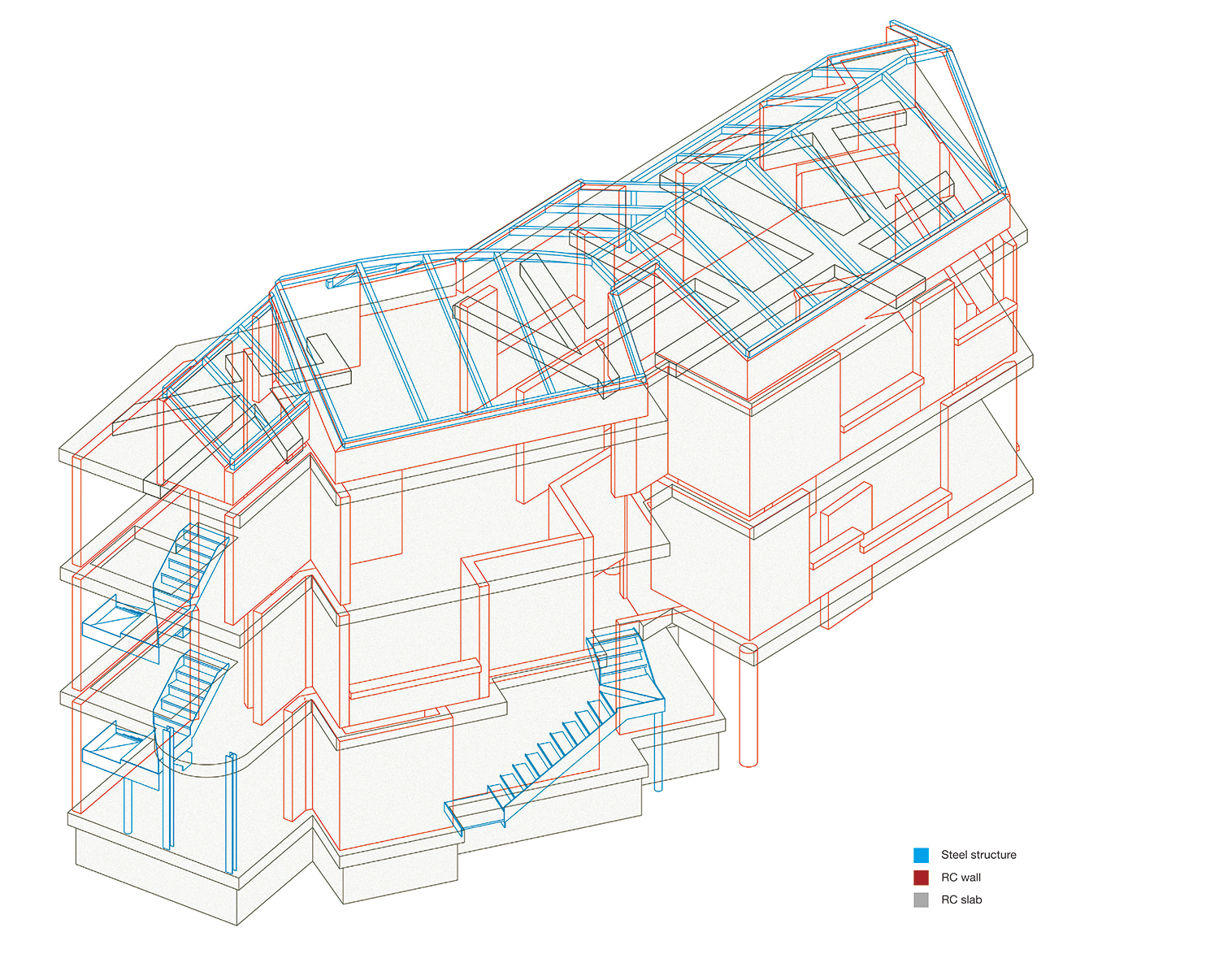

Structural diagram

Order Created by the Small Elements of Everyday Life

Similar to its neighbouring homes, our design features a gabled roof and a modest three-storey mass. Between the stacked slabs, varied architectural elements such as different windows and sills, eaves and balconies opening outward, exterior stairs connecting to the street, and terraces projecting toward the intersection like lookout points—wrap around the building. Meanwhile, typically concealed components such as downspouts and exhaust vents are intentionally exposed, allowing water, smoke, and smells to flow outward. These architectural details, alongside people’s belongings, become aspects of a canvas for the lived-in texture of the house.

A House Like a Village

We believe that architecture should be beautiful, and there is particular beauty to be found in the vernacular home. It is the beauty of human life taking form, akin to the erratic nature of wildflowers blooming in a forest. We see the relationship between city and architecture not as oppositional or of something where one includes the other, but as two worlds with different characteristics that coexist within a single frame—like a reversible garment that can be worn inside out. This exploration of ‘private publicness’ begins with the idea of homes that embody an openness born from daily life and human encounters in the city—creating a lived landscape, rather than a genre-defined public space for the masses. These are private spaces that, by flowing outward, take on a certain public quality. They form small public places between the home and the city, emerging as the traces of everyday life made visible. When architecture stands in the village as both a gathering of extended families and a collective of small orders, transmitting individual lives outward, it can begin to restore a sense of communal publicness that has faded since the modern era.

o.heje architecture (Lee Haedeun, Choi Jaepil)

Kim Donggyeong, Lee Jiyoung

Seocho-gu, Seoul, Korea

multi-household house

177.7m²

106.1m²

199.7m²

3F

11

11.27m

59.7%

112.3%

RC, steel frame

exposed concrete, stucco, galvanised steel sheet

water paint, wooden flooring

Eun structural engineering

Daedo Engineering

Jayeon & Woori contractor

Sep. 2023 – June 2024

Sep. 2024 – June 2025