The Southeast Asian architect interview series, which began in January 2021, is now heading to Malaysia and Taiwan through Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam. Countries in Southeast Asia have different historical backgrounds, surroundings, religions, and so on, but connections to the climate are often noted. In particular, based on the tropical climate, the relationship between internal and external spaces and an interest in nature and tradition are naturally linked to modern architecture, creating unique identities in each country. How about Malaysia? BC Ang and Wen Hsia Ang who were born and grew up in Malaysia, run WHBC Architects and we met them in writing to hear stories ranging from their observations of the current situation of the country and of their construction projects in the city.

interview BC Ang co-principal, WHBC Architects × Park Changhyun principal, a round architects

Park Changhyun (Park): Malaysia is densely populated in its metropolitan areas. Various urban planning policies are being established to contend with the rapid economic growth that began in the late 1990s and solve the resulting overcrowding of urban centres, but unlike Singapore, a clear solution to overcrowding in the metropolitan area has yet to be found. What is the current level of the population concentration in Malaysia?

BC Ang (Ang): Before we focus on the situation in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia, it would be useful to compare the situation in Malaysia, Singapore, and South Korea. According to countries in the order of land area, Malaysia is about 330,000 km2, Korea is 100,000 km2, and Singapore is 730 km2. Malaysia is the significantly larger country, three times the size of Korea and 452 times that of Singapore. However, the population is about 33 million less than Korea, which has about 52 million people. The population density is 100 people/km2 in Malaysia. Although it is lower than Korea, which has 520 people/km2, the density difference will decrease if the area is narrowed to the city’s scale, which is the capital and nearby metropolitan area. Kuala Lumpur has a density of about 2,900 people/km2 and Seoul has 2,200 people/km2. The level of overcrowding in the metropolitan area of Malaysia and Korea is similar.

Park: It’s very interesting. Although countries may have historical backgrounds and urban development processes that have been in operation until now, it is likely that they have common concerns about how to solve the problem of overcrowding in an urban way.

Ang: I don’t think there’s a clear right and wrong in policy- making in urban planning. Urban planning is design, and design is finding a good balance in the context of each city or country. Each city has a different climate, terrain, culture, history, politics, and economy. Strategic urban planning policies are important, but more importantly, it takes as little as years, as many as centuries, to monitor the situation and implement them flexibly.

Park: I agree. Korea is also developing new local cities and new cities by implementing an autonomous decentralisation policy, and I think it is more important to continuously monitor and improve the city than it is to create it for the first time.

Ang: It is the same as creating a garden or cultivating a bonsai tree. When planting bonsai trees, you cannot cut them into the shape you want on the first day. Years of daily management and daily refinement are required to produce good results. However, we need a gardener with the most essential vision.

Park: Urban expansion generally follows the expansion of density and area. First, the expansion of density is ambit of high-rise buildings with a high volume due to the development of building technology. However, in this case, urban infrastructure is excessively concentrated in one place and life is less pleasant. The second is urbanisation, which consists of the expansion of the area, which is directly related to the transportation infrastructure that connects to nearby areas. Looking at many Southeast Asian countries, including Malaysia, people do not use public transportation such as railway facilities, and most of them use motorcycles and passenger cars to cause traffic jams. What do you think is the problem and direction of Malaysia’s urbanisation process?

Ang: To continue with the aforementioned stories of three countries, in Singapore, the entire population lives in the capital city, with 50% of the population concentrated in Seoul and the metropolitan area. However, only 25% of Malaysia’s population lives in Kuala Lumpur. Relative to the area of the city, in terms of thepopulation density, Kuala Lumpur is 2,900 people/km2 that is slightly higher than Seoul with 2,200 people/km2. On the other hand, Singapore is 8,200 people/km2 that is nearly four times higher than that of Seoul and Kuala Lumpur. Nevertheless, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, when compared to the quality of the environment and quality of life for the two cities, many people think that Singapore is much more. This is an interesting point about our conversation. Perhaps the density of a city is not related to the quality of its environment? Then, is Korea’s decentralisation policy correct? Many questions arise. However, since Malaysia is also going through a similar process as Korea, it is necessary to examine the autonomous decentralisation policy implemented in Korea in advance.

Park: I think discussing the direction of urbanisation is also important socially and emotionally, but is Malaysia open to anyone? Moving from the same context to the architectural aspect, I wonder what direction in which Malaysian architects are actively engaged? Do you try to meet the demands of the city within the city centre? Or do you tend to look out of the city?

Ang: Urban planning policy in developing countries is heavily influenced by politics and the economic interests behind them; in particular, in countries where governments made up of multiple parties can be said to be absent or excessively democratic, most decisions are made in time for election cycles. So it is often not the best design but the result of political and economic influences. Even their interests change rapidly with the seasons. How can we secure a good urban planning policy that is not public but can maintain a greater profit? This question leads to the question of who the Malaysian gardener is—will Malaysia hire a gardener who design cities skillfully or will it continue to hire more managers? Can we hire a good gardener in Malaysia, when racism remains? What should a gardener do to avoid being influenced by stakeholders? Many questions have no choice but are back-to-back.

Park: A detached house known as the ‘Tropical Box House’ was designed in a suburb of Kuala Lumpur filled with complex situations and unanswered questions. Located in Bukit Damansara, a wealthy residential area, the project to design a space for five families on a 10,500m2 site would have been relatively free from the urban, political and economic constraints we have previously talked about. What did you focus on when you designed this house?

Ang: The theme is a concrete tropical box enveloping a dense jungle. The house is designed to be an inward looking space that blocks the hot sunlight and rain of tropical climates while embracing the abundance of nature inside and outside the house. Considering climate conditions, concrete structures such as egg crates were designed to enclose the building, blocking heat but allowing adequate sunlight to create a comfortable interior space.

Park: Looking at this house of exposed concrete reminds me of modernist architecture. The composition and format are so high that it is not awkward to be built in any village in France.

Ang: Exposed concrete is reminiscent of modernist architecture and may feel very cold when used in temperate areas, but we have come to use it inspired by how materials are used differently in different countries. In particular, it referred to India and South America. Exposed concrete is thought to express the most natural properties of materials in tropical areas.

Park: As the project name Tropical Box House suggests, the relationship between nature and space is important. How did you interpret the surrounding nature and connect it to this house? I am curious about the stories of what I expected when I chose this structure and what I actually implemented in architecture.

Ang: The 900mm-thickness egg-crate envelope structure is made of field-mounted concrete. The natural environment we consider includes not only vegetation like trees but also sunlight and wind. As previously said, adequate light and wind are passed through, but UV rays are blocked, and concrete pins 150mm thick are placed rhythmically to adjust the intensity of light more carefully. It also has a large hole so that the surrounding vegetation can extend into the house, so that the interior and exterior boundaries of the house can be blurred. Egg crate structures look heavy on the surface, but they meet lightly with the ground, sit between trees, and help the landscape grow inside them.

Park: Compared to the previously designed housing project, the Tropical Box House is large in size, and its use of format and materials is simple. Please explain the composition of the interior space and the relationship between the land and the building.

Ang: Most of the houses were planned to be elevated and placed on sloping land to be at eye level with the trees. Major spaces such as living rooms, restaurants, swimming pools, and so on are located on the side of the entrance or at a high level. The bedroom is upstairs, and the parking lot and service area are downstairs. If you float a building from the ground, it will reduce moisture and pests. It is advantageous to maintain the air and dryness of the house. To get inside the house, you have to cross the bridge on the side through the tall Albizia tree. If you go to a relatively narrow passageway that leads to the entrance stairs and next to the courtyard, you will reach the open living room and open your eyes to the swimming pools and gardens.

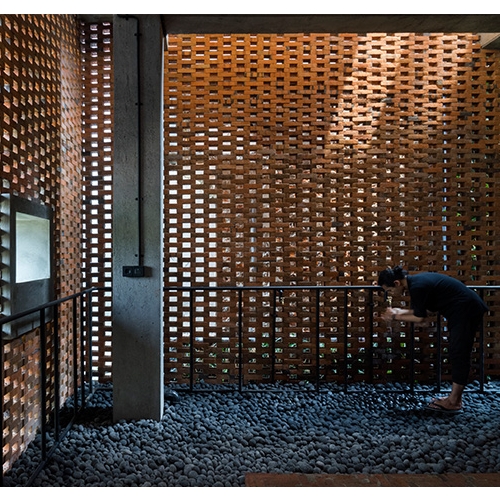

Park: The ‘Asli’ project, which is seen as a significantly different approach and outcome from the Tropical Box House, is also interesting. The Kampung Pian region, located in Pahang, Malaysia, was selected as the venue for the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples 2013, a project to create showers and toilets needed for the area. In light of a project that seems to have a strong impact on traditional and regional characteristics, what characteristics does Kampung Pian have?

Ang: Located next to the Krau River, an indigenous village, Kampung Pian consists of more than 50 Jahut tribes residing near Malaysia’s largest wildlife reserve. The Jahut tribe lives by farming crops such as rice and corn. Some residents work at palm oil factories, rubber farms, fish in rivers, and make a living out of jungles such as rattan and petai. Most of the residents live in wooden houses that are finished with bamboo shells and straw-weave thatched roofs. These Kampung Pians were selected as the venue for the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples 2013, which required showers and toilets to accommodate the residents and 200 participants. The facility had to be part of a community hall for village events after the event. We are inspired by local architecture that has responded effectively to the fluctuations in the climate and the environment. It has large roofs and porous walls that are safe from flooding and wildlife and manage to keep the interior space cool.

Park: Compared to the Tropical Box House, the period and cost would have been limited. Perhaps this is why the steel scaffolding was built on a concrete foundation and covered with wooden trusses and acrylic sheets.

Ang: The project lasted six weeks. We found a system that could stand on its own feet easily, quickly and inexpensively, and judged that steel scaffolding was the best fit. In addition, if space is created with a scaffold of 4 × 6ft (approximately 1,200 × 1800mm), it is perfect for a single shower room and toilet.

Park: The use of handcrafted materials, considering the way in which the members are connected, is also very interesting. How was Asli constructed?

Ang: The cherry and nipa palm leaves obtained at the scene were tied with rattan to bamboo supports and the walls were secured to the scaffold structure. The fabricated walls are naturally ventilated, maintaining a bright and dry interior at all the time. The door is made of waterproof PVC canvas, which uses a sarong, a cloth that is usually worn around the waist in Southeast Asian countries. The wooden elements decorated at the top were carved with peacock patterns by village elders in figures unique to the Jahut tribe. These traditional techniques, such as weaving, knots, and crafts, demonstrate the diversity of indigenous peoples and the heritage and identity of tribes.

Park: Were there any difficulties in modernising the technology that has long been passed down in a given region?

Ang: The only weakness in local architecture is that the structure often becomes unstable after a few years. When that happens, local residents retrieve reusable materials from old structures and rebuild the new building. Therefore, on top of a simple and permanent structure, it devised a method of adding traditional art and crafts. It is designed so that residents can easily maintain their own skin in the long term as it can be made with traditional techniques using local materials.

Park: What do you think tradition is?

Ang: Tradition is always thought to be a lesson learned from the wisdom gained over many years, and from generations of trial and error. But we must always be practical and look at tradition as the times change. We should compare the situation with when it first started and allow traditions to evolve and develop.

Park: I could hear the WHBC Architects’ thoughts on tradition, modernity, nature and artificiality by looking at the two projects of different nature that you designed. I think the points of concern will be shared, even though the ways of connecting the past, present, and future and responding to change are different. I look forward to meeting you in Seoul or Kuala Lumpur after the pandemic.

http://www.whbca.com/

http://www.aroundarchitects.com/