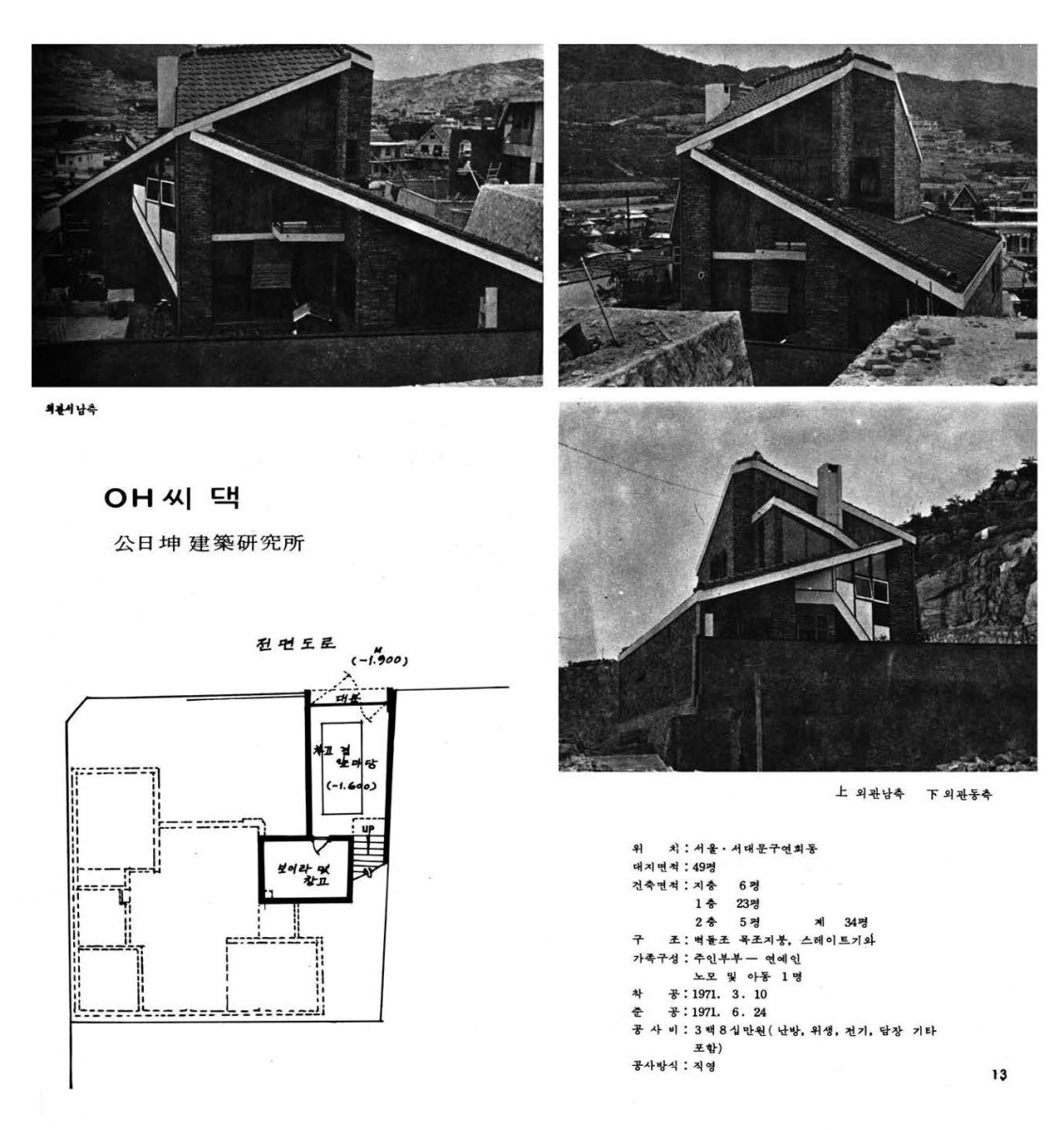

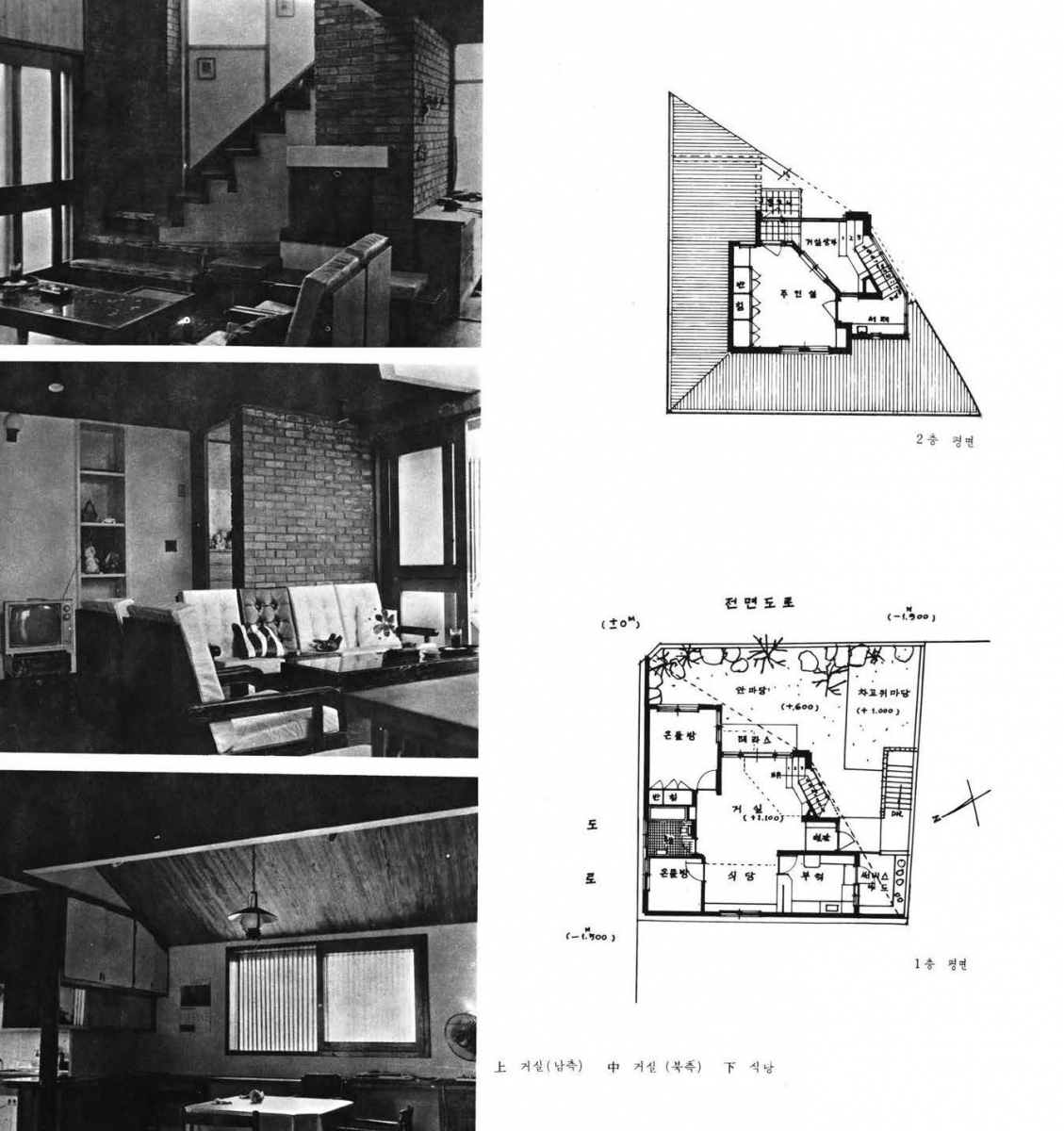

The ‘Residence for OH’, as featured in SPACE No. 56 (July 1971), is a small detached house of 34-pyeong (about 112㎡). It is impossible to know whether it reflects the personality of the owner ‒ who is a celebrity ‒ or whether its styling was simply the architect’s preferred means of expression; the house features a triangular plan that is sharp like a piece of broken glass as it is wide and flat like a stingray. The Residence for OH, which possesses a strange aspect made evident not only in the plan but also across the exterior, emerges somewhat unexpectedly on the square-shaped site of the hilltop in Yeonhui-dong, Seodaemun-gu, with a stone mountain as its background. A parking garage has been placed underground by drawing on the difference in levels between the two sides on the east side, which face the road with a height difference of close to 2m, and the remainder was filled to form an embankment. This meant that the functional rooms on the first floor, along the two sides along the northern embankment, could be drawn more closely to the site boundary without the need for a fence. This seems like a reasonable choice, if only to secure even a little more space for the courtyard on this small plot of land. The main gate to the house is adjacent to the entrance for the underground parking lot, so you can only enter the house after passing through a rather low and dark garage. Imagining the way in which the house will be revealed gradually as one ascends the stairs, as well as seeing the household goods in the ‘service yard’ that will be out in the sun come into view, it must have been quite an emotional approach. The floor plan is very functional and compact, similar to that of an apartment, although it breaks up any monotony by placing a void towards the courtyard. Looking over the entire site, the area of the required functions ‒ such as the entrance hall and the courtyard ‒ is in contact with the living space placed in the middle, when viewed from all sides. However, because it was intended as a truly south-facing house on a square-shaped land on a nearly 45-degree tilted angle, the rooms are grouped in a zigzag-shaped cluster on the north side, crossing the land diagonally. What further maximises this impression is the end line of the roof that runs from one corner of the site to another, and yet of greatest interest, aside from the dotted roof line drawn on the architectural drawings of the first floor, is that it is not easy to guess the shape of the roof just by observing the first floor plan of this house. At a glance, the formal aspect of the roof and the function of the plan can be read discontinuously, as if the roof was covered separately after initial drafts of the plan. Some clues, however, allow us to infer the efforts made on the part of the architect to integrate form and function within a single organism as opposed to subordination or confrontation. Not only do both of the roof’s endpoints on the first floor meet the fence exactly at the corner of the east-west axis of the site, but the roof’s corner in the living room courtyard also serves as the starting point for another feature in roof geometry on the second floor, making the entire house ‒ including the fence ‒ look like a single work of origami. Furthermore, the southern corners of the ondol room, the entrance hall, and the kitchen space also meet the roof line exactly at this point of contact, which is especially accurate given the fact that the area and proportion of each room are linked to the roof. As a result, various triangular eaves of different heights and sloped sides exist in this house. Strictly speaking, one hesitates over referring to them as eaves—perhaps it is more accurate to refer to them as ‘remaining roofs’ because they attempt to entirely cover the roof plates according to the plan. This is an incomplete, fragmented element which has been agonised over, sitting between aesthetic and ethical concerns in using the residual fragments after a single completed form had been functionally segmented.

SPACE No. 56, p. 13.

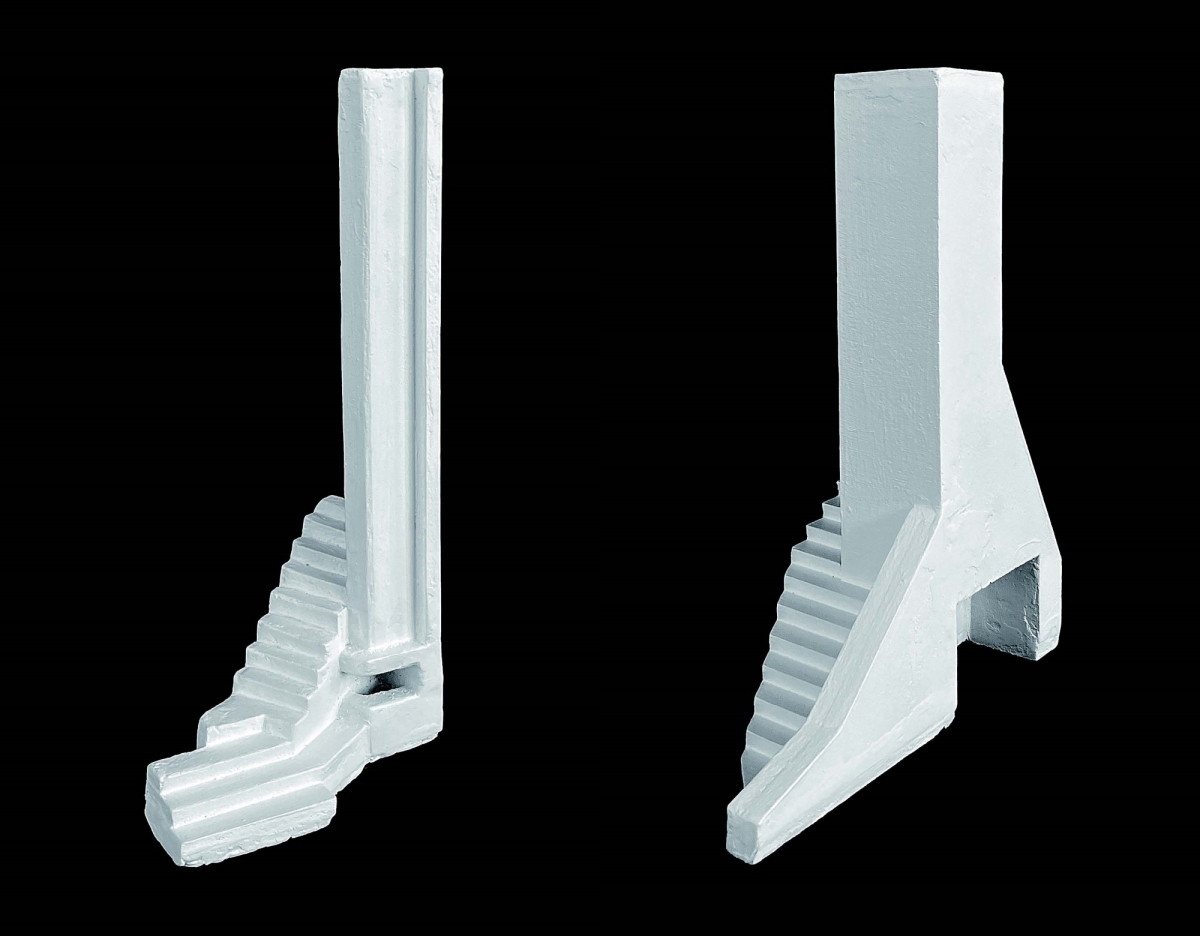

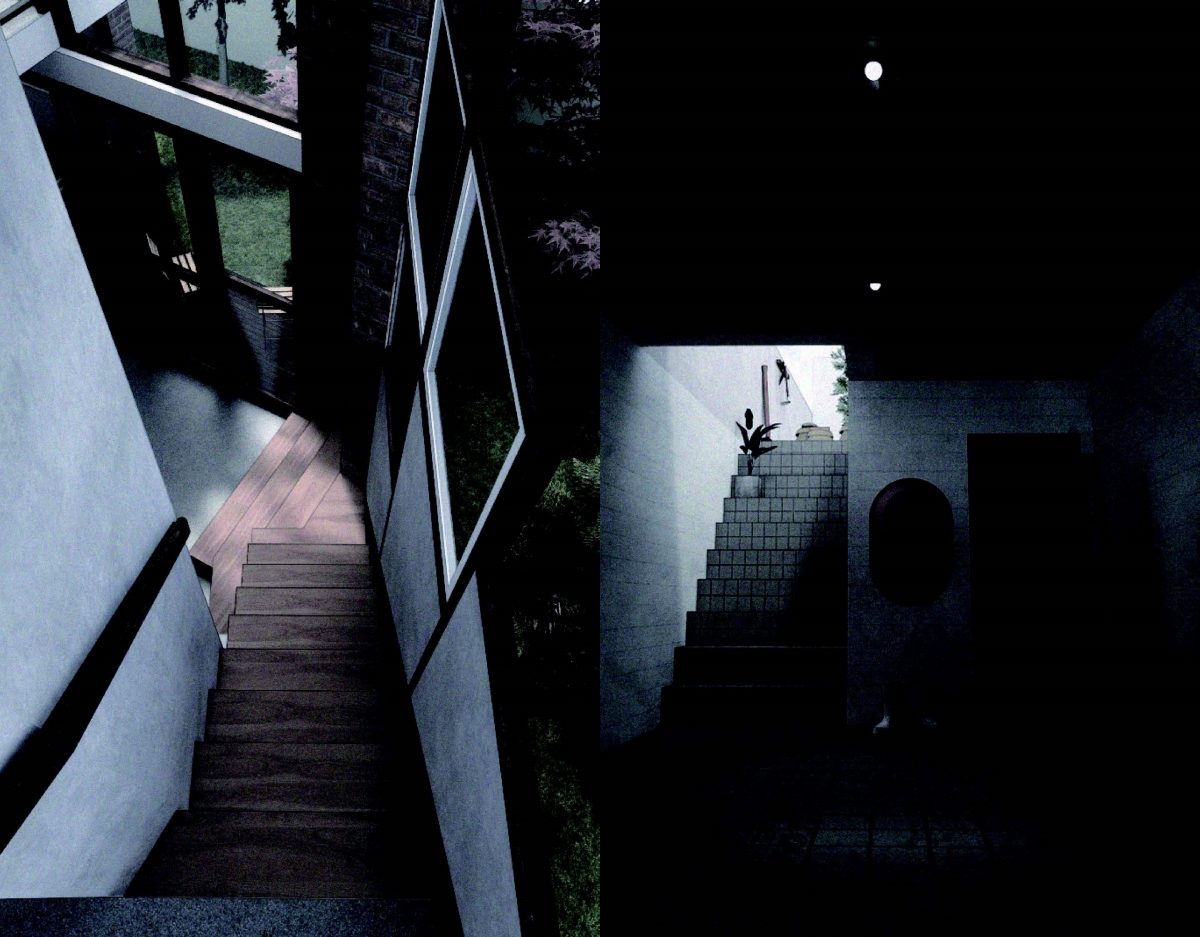

Although the more bizarre character of this roof and its shape is apparent at first glance, the aspect that requires the keenest attention in this house is the staircase leading up to the second floor. This is because it is the decisive figure which sought to seek a compromise between the roof’s formal desires (ideal) and the plan’s function (reality). As previously mentioned, it is evident that the architect has channelled significant efforts into the organic form of the roof. At the same time, it appears as if he found it unacceptable to draw plans featuring distorted rooms. After all, the emotional baggage of that ambivalence finds expression as the deformed staircase, and if you carefully examine each step ‒ as if ascending the stairs ‒ you can picture how painstakingly the architect drew each step. The first step starts out rather wide, following the orthogonal grid of rooms. Given that it is almost the same width as the terrace, it appears to be a good 1.2m wide. Much like the first step of a typical staircase, this marks the starting point of the vertical circulation, but it also looks like the step is part of the living room, because the width of the stair is so wide ‒ considering the size of the space ‒ and this is made even more as one of its lateral sides has been left open. The second step is the place where the plan’s orthogonal grid and the roof geometry’s diagonal line meet, and the step extending to the right side along the roof line appears to be a fireplace shelf. One still hesitates over whether it can be called a true set of ‘stairs’. From the third step, at last, it becomes the pure vertical circulation recognisably of a set of stairs. When compared to the first and second steps, the width has been significantly reduced here, and a part of it is blocked by the L-shaped load-bearing wall on the left side to support the roof, denying the stair’s pure function once more. It seems as if it may have been difficult to move or remove the L-shaped bearing wall: each corner in each room that comes into contact with the roof as one proceeds to the courtyard, away from the stairs, should have been readjusted, and so the wall would have been required to bear that sense of mass. The stair still adheres to the orthogonal grid of the room. After all, the fourth step features a hexagonal tread that harmonises the diagonal roof line and the straight line of the room. As a result, it now becomes a sole ‘stair’, and just as the chimney wall is formed, resulting in an effective width of up to 70cm. Even here, adjusting the position of the chimney would have proven to be difficult, because if the chimney was relocated even slightly inside the living room, the organic relationships ‒ with the living room area, the shape of the void, the wall of the basement boiler room, and the entrance ‒ would all be broken. The stair then runs in a leisurely way up through the roof of the first floor, leaving just the internal formative principle. It is a point that reminds us of the stairs of the Vanna Venturi House (1964), an active involution rather than an exclusion of an existing context. Similarly, the stairs in the Residence for OH also communicate the architect’s inner life, which is manifoldly com-pli-cated.

The person who designed the Residence for OH in Yeonhui-dong was the architect Kong Illkon. Born in Byeok-dong, Pyongan-do in 1937, he defected to South Korea during the Korean War, graduated from Seoul High School, and earned a bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Seoul National University in 1960. At Kim Swoo Geun Architecture Institute, for nine years from 1961, he was in charge of major projects such as the Freedom Center and Munhwa Broadcasting Corporation in Jeong-dong. Then, in 1969, he opened his own office, and Kong Illkon undertook not only orthodox and well-organised private residences ‒ including the Residence for OH, Residence for K (SPACE No. 40), Residence for C (SPACE No. 44), and Residence for Musician J (SPACE No. 104) ‒ but also large and small projects, eventually receiving the 1st Special Award of the Korean Institute of Architects for the project at Chung-ang University, the Central Library on Anseong Campus. With a six-year age gap between him and Kim Swoo Geun, and at the same age as Yoon Seungjoong, he is an important figure in the history of Korean contemporary architecture and founder of Mokguhoe with Ahn Youngbae (born in 1933), Kim Byunghyun (born in 1937), Yoo Kerl (born in 1940), and Kim Won (born in 1943).▼1 Nonetheless, why isn’t he better recognised among those of our generation, including myself? I tried to look up some materials but there was extremely little information about Kong Illkon, much less his monographs. Among them, a brief study published in SPACE No. 93 (Feb. 1975), entitled ‘Architectural View, Organisms, and Nostalgia through One’s Own Work’, provides a clue concerning the internal conflicts he faced as an artist. Perhaps it originated from an introspective attitude of humbly agonising over design aspects and acknowledging that he is caught between the desire to create a ‘perfect work’ in the manner of an organism and a self that has no choice but to adapt to the changes in the world. It is said that he was ‘a genius in his profession, but indifferent to what’s going on in the world’, one who continued to wear a tie for 20 years, without paying much attention to modern trends. As Kim Swoo Geun stated, he was an artist rather than an architect, and he was a philosophical figure before he was an artist.

‘I should have lived in a rural area as a countryman, dreaming of building a house where owls fly in and out. Why struggle in vain as a role as an accessory in a city that functions like a massive machine? Even I consider myself deplorable.’▼2

Thinking about an architect who blamed himself in this way makes me reconsider today the fate and role of the architect, who, by nature, has no choice but to think about the existence of human lives and of their own life within this broader system.

The stairs in the Residence for OH and the stairs in the Vanna Venturi House. 1:30 model (production: Bak Sunmin) ⓒSuh Jaewon

One day in May, when the sun was shining brightly, I found the address at last and went straight to the Residence for OH.▼3 Unlike 50 years ago, it was now surrounded by unappealing buildings, yet it retains its imposing nature as if representing the architect. Other than the chimney that has been in part removed and the walls that were newly coated with Dryvit, it was almost entirely intact, without any major changes. The courtyard and the external walls were completely covered with lush green, as if they cared nothing for the outside world. When I asked those living in the house next door, the neighbour said there were still people living there. With excitement, I immediately thought that it ought to be archived for the sake of the history of Korean contemporary architecture, but I soon became unsure as to whether the architect Kong Illkon would be pleased or not. Therefore, I put my trivial thought aside.

(left) The view looking down the stairs (rendering: Choi Jangmin) ⓒSuh Jaewon / (right) The entrance from the garage (rendering: Choi Jangmin) ⓒSuh Jaewon

In our next issue Shin Chunghoon will cover Lee Ufan’s ‘Trends in Japanese Contemporary Art: Focusing on the Contemporary Japanese Art Exhibition’, which featured in SPACE No. 32 (July 1969).

Photos of the present condition of the building ⓒSuh Jaewon

-----

1 Mokguhoe is the name of a group of architects founded in 1965. The name originated from a monthly gathering, held on the first Thursday of every month, of students from different years at Seoul National University’s Department of Architecture to dine and passionately discuss architecture. A year later, Hongik University’s Geumwoohoe and Hanyang University’s Hangilhoe were established, and it is known that they served as a catalyst for serious discussion of Korean architecture.

2 ʻArchitect Kong Ilkon (Lee Segi’s Exploration of Characters: 17)ʼ, Seoul Shinmun, 23 Feb. 1993.

3 The address of the Residence for OH is 1-33, Yeonhui-dong (382-10, Moraenae-ro), Seodaemun-gu, Seoul. It is almost entirely intact, except that the ‘service yard’ has been closed off and converted into an interior space. Its 3D model can also be viewed online via the Kakao 3D map or the S-Map.