SPACE June 2023 (No. 667)

In Search of Park Kilyong’s Architecture: An Argument Against the Question, ‘What If Park Kilyong Was Not the Architect of Bohwagak?’

Front view of Bohwagak ⓒPark Youngchae

Park Kilyong (1898 – 1943) was one of the most prolific architects in Korea during the Japanese occupation. He is said to have designed around 200 structures, including the Hwashin Department Store, the most famous building in colonial Gyeongseong. However, as Hyon-Sob Kim argued in his article published in SPACE No. 662, there is no hard evidence to determine their authenticity of some of the buildings that have been attributed to Park. This applies not only to Bohwagak, which Kim questions, but also to the Pak No-soo House in Okin-dong which was designated as Cultural Heritage Resource No. 1 by the Seoul Metropolitan Government in 1991, as well as the Donga Department Store. I think the root cause of this controversy is that the architect died too young, and his achievements were not properly accounted for or documented. Later, during the Korean War and subsequent social turmoil, many documents were destroyed, making it difficult to create an accurate list of his works. So far, the buildings that can be reliably attributed to Park are only those published in Joseon and Architecture (May 1943), the Japanese construction company Shimizu Corporation’s Yearbook of Construction and the Architectural Drawing Collection of Houses, and those featured in Korean daily newspapers. Except for these examples, unless new documents will be discovered in a coming future, there is no way of verifying the authorship of the works.

However, identifying the designers of these buildings is not that difficult. There were only a few architects working in colonial Joseon in the 1930s. Besides Park Kilyong, Park Dongjin (1899 – 1980), Yi Hunwoo (1886 – 1937), Park Injun (1892 – 1974) would be on the list, but architects other than Park Kilyong carried out a very limited number of projects. Moreover, Park was almost the only architect in Gyeongseong in the 1930s who was able to design the modern style building. Of course, there were other Japanese architects who worked in colonial government, such as Japanese Government-General of Korea, but it was very rare for them to take on private projects for Koreans. Nakamura Yoshihei (1880 – 1963), who opened the first Japanese architectural office in Gyeongseong, was exceptional. In this situation, I think that the works can be recognised as coming under his design if their close connection can be proven through the comparison of characteristic floor plans, facilities, structural methods, and window details found in Park’s works, and most importantly, through a review of Park’s architectural theories published in many magazines and newspapers. Therefore, this article will focus on the relationship between Park Kilyong and two buildings, Bohwagak and Pak No-soo House to establish their authorship. Even after they are provisionally determined to be his works, I will revise my claims if other clear evidence is found.

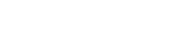

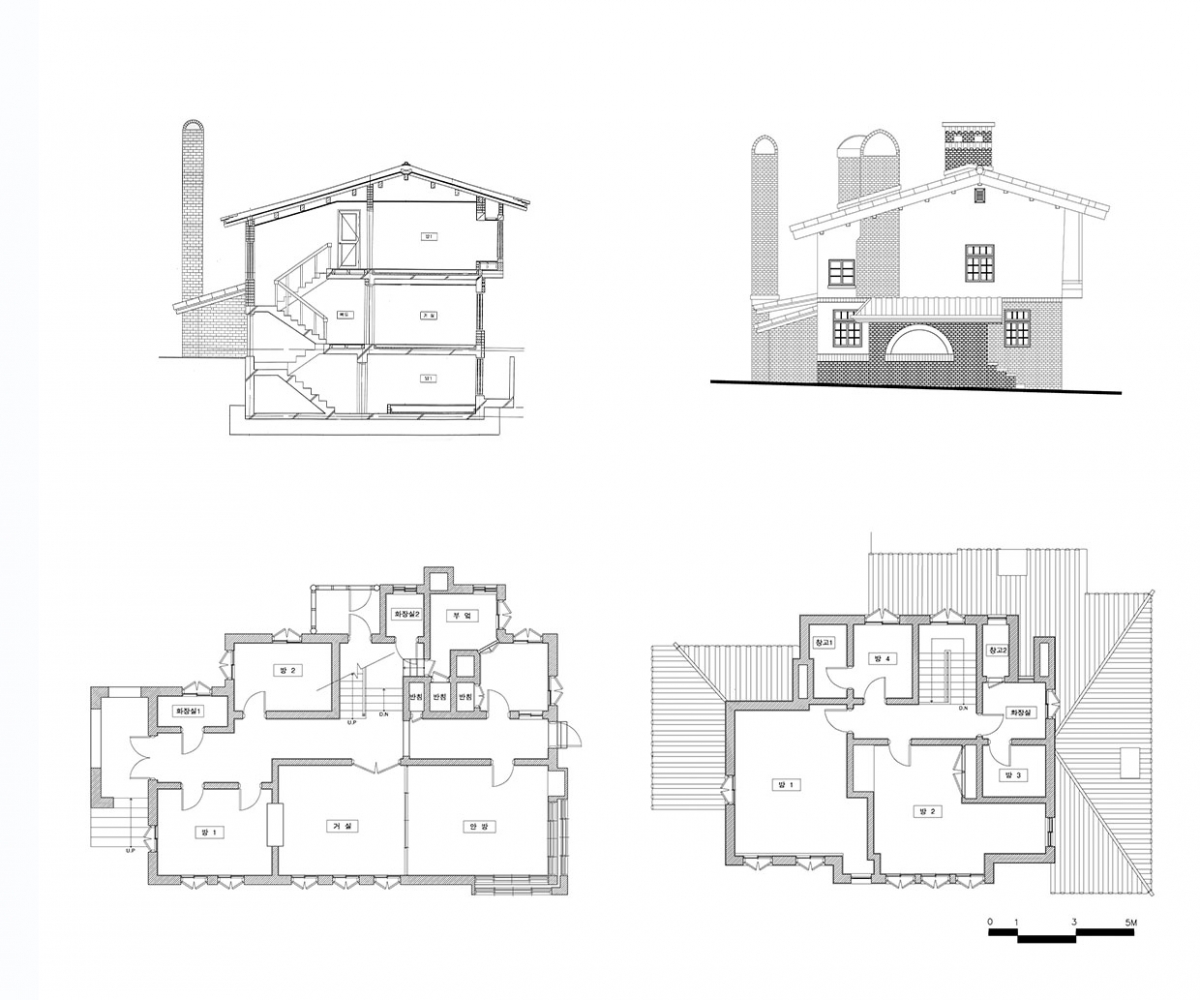

Plans for first amd second floors of Bohwagak (field survey by Architectural and Urban History Lab., Hanyang University ERICA)

Bohwagak

The website of Kansong Art and Culture Foundation explains, ‘Bohwagak was designed by the Korean architect Park Kilyong. After graduating from Gyeongseong Technical College (the predecessor of College of Engineering, Seoul National University) in 1920 and working for the architectural bureau of the Japanese Government-General of Korea, Park established his own architectural practice in July 1932 in Yeji-dong, Jongno-gu.’▼1

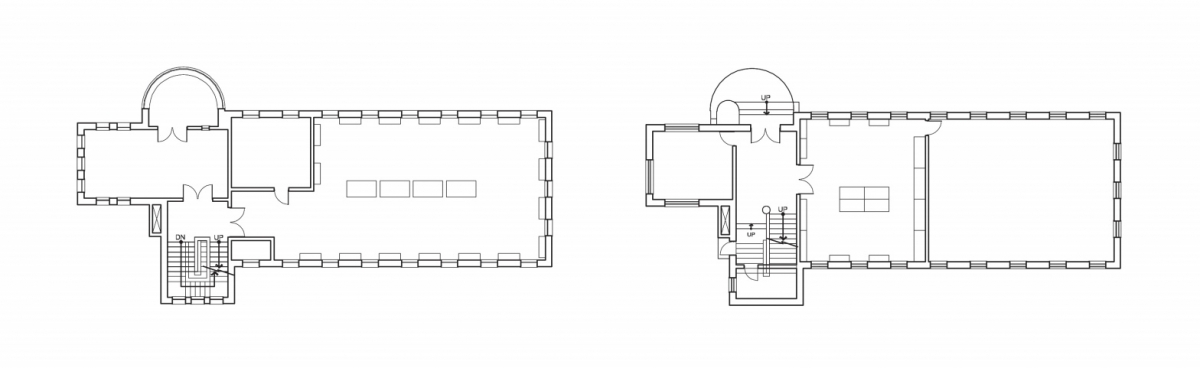

Referring to the building’s construction date, it also noted, ‘Finally, on 5 of July leap month, 1938, the first private museum in Korea, Bohwagak, was inaugurated.’ However, until now, it hasn’t been known how Bohwagak was designed, as there was no proper list of his works. Only a narrow range of buildings still remain, which makes it difficult to understand his design approach by comparison. Luckily, however, a previously unknown Mr. B House▼2 by Park Kilyong was discovered in the Architectural Drawing Collection of Houses constructed by Shimizu Corporation, which helped us to locate similarities with Bohwagak in the floor plan, structure, and windows. The same house also appeared in the Yearbook of Construction published in 1937 by the same corporation, where it was labeled as Min Byeongsu House.▼3 The house was constructed in December 1936 in Cheongun-dong, Seoul, about two years before Bohwagak. Despite their difference in programme, Bohwagak and the house first show similarities in their floor plans. They are characterised by a semicircular mass that protrudes from the left side of the plan. Of course, Bohwagak differs in that it cantilevers over the first floor, while Min Byeongsu House uses the first floor as a reception room and the second floor as a terrace.

From the 29th of July to 1st of August, 1936, Park wrote a series of four articles entitled ‘The Modern and Architecture’ for Dong-A Ilbo. They appear to be four serial publications of his long-developing thoughts rather than separate articles on different topics. The last of the four articles, published on the 1st of August, 1936, is subtitled ‘The Criticism of Famous Buildings in Gyeongseong’ and presents the four architectural goals that he was pursuing at the time: ‘① Architectural form is an inevitable expression of function. ② A simple form without falsehood is the most beautiful. ③ Modern strong beauty is found in the most material aspects. ④ Dynamic expression is one of the most unique modern trends.’▼4

Based on these criteria, Park categorised the major buildings built in Gyeongseong at the time into four grades which clearly reveals his architectural orientation.Of course, he applied these four criteria to his own building designs. He used existing historicist motifs on the Hwasin Department Store at the request of the client, but, given freedom to design, he tried to follow these principles. Bohwagak and Min Byeongsu House are two buildings that exemplify Park’s criteria. Both buildings have a simple form that express their function in a dynamic way. This dynamic expression is especially important because it is also characteristic of the main building of Gyeongseong Imperial University, whose design is also thought to have involved Park. While the design of the main buildings of the Faculty of Medicine and the Faculty of Law and Literature are strictly symmetrical, the main building of Gyeongseong Imperial University is the only building designed as asymmetrical composition among buildings on the campus. Both Bohwagak and Min Byeongsu House shows a similarity in having a semi-circular protruding mass, which balances the overall asymmetry of the building form.In addition to this similarity in floor plans, they are also very similar in structural method. The white cubic building of Bohwagak is reminiscent of the modern style of the 1920s, so it’s easy to assume that it was built based on Le Corbusier’s Dom-ino structure.

However, the photo of its construction site shows that this was wrong. The structure is made of concrete slabs on top of 2B thick brick load-bearing walls. For this reason, it lacks tectonic clarity which can be found in reinforced concrete structures. This method was first used in colonial Joseon in the early 1920s in christian educational facilities, but as mainland Japanese trends influenced colonial Joseon after the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923, major public buildings in the late 1920s adopted fully reinforced concrete construction. Park Kilyong had already used reinforced concrete structures when he designed Hancheong Building (4 floors, 1934 – 1935) and the Hwasin Department Store (7 floors, 1935 – 1937). On a smaller scale, however, he combined masonry and a concrete structure.

It is no coincidence that Bohwagak and the Min Byeongsu House, built in the late 1930s, used the same structure, and I believe this reflects Park’s ideas.This structure creates a unique window form. Concrete beams at the edges of the building act as lintels for windows, making it possible to create relatively wide windows. As a result, decorative lintels became unnecessary, creating a relatively simple appearance. Park used both sliding and hinged windows in his buildings at the same time, but the latter best represent his unique design style. The masonry made thick walls, which can accommodate double windows. In this case, the inner windows are designed to be opened to the inside and the outer ones to the outside. I believe this windows system was adopted in preparation for cold winter in Korea. Moreover, the windows created a unique grid pattern. In his architecture, wide windows are divided into horizontal and vertical panes to create a lattice-like pattern. This method seems to be one of the main motifs defining his architecture, which is also present in the windows of Pak No-soo House and exhibition hall on the first floor of Bohwagak.

Plans for first and second floors and front view of Min Byeongsu House (source: Shimizu Corporation, Architectural Drawing Collection of Houses, 1939, p. 119)

Pak No-soo House

Like Bohwagak, the Pak No-soo House can be also proven to have been designed by Park Kilyong. Here, we can examine its relationship with Park from three perspectives. First, we can see that the house is characterised by a middle corridor, of which rooms are arranged on both sides. This feature is shared by both the Pak No-soo House and Mr. Yun House in Sindang-dong, which was also designed by Park Kilyong.▼5 Based on the year of the design, it seems that Mr. Yun House was slightly earlier. Construction began in May 1938, but wasn’t completed until March 1939. In comparison, Pak No-soo House was completed in May 1939 and a housewarming party was held in August 1939. Comparing the two houses, we can see that the layout of the rooms on the first floor is almost identical. The only difference is that the dining room is located on the north side in Pak’s house and the south side in Yun’s house. This makes the kitchen in Pak’s house look a bit narrow. This difference can be easily explained in accordance with the site conditions or the client’s requirement, so we can see the striking similarity between the two plans, which were designed around the same time. Especially considering that both houses have double corner windows which were quite rare at the time, it is quite possible that they were designed by the same architectural firm.

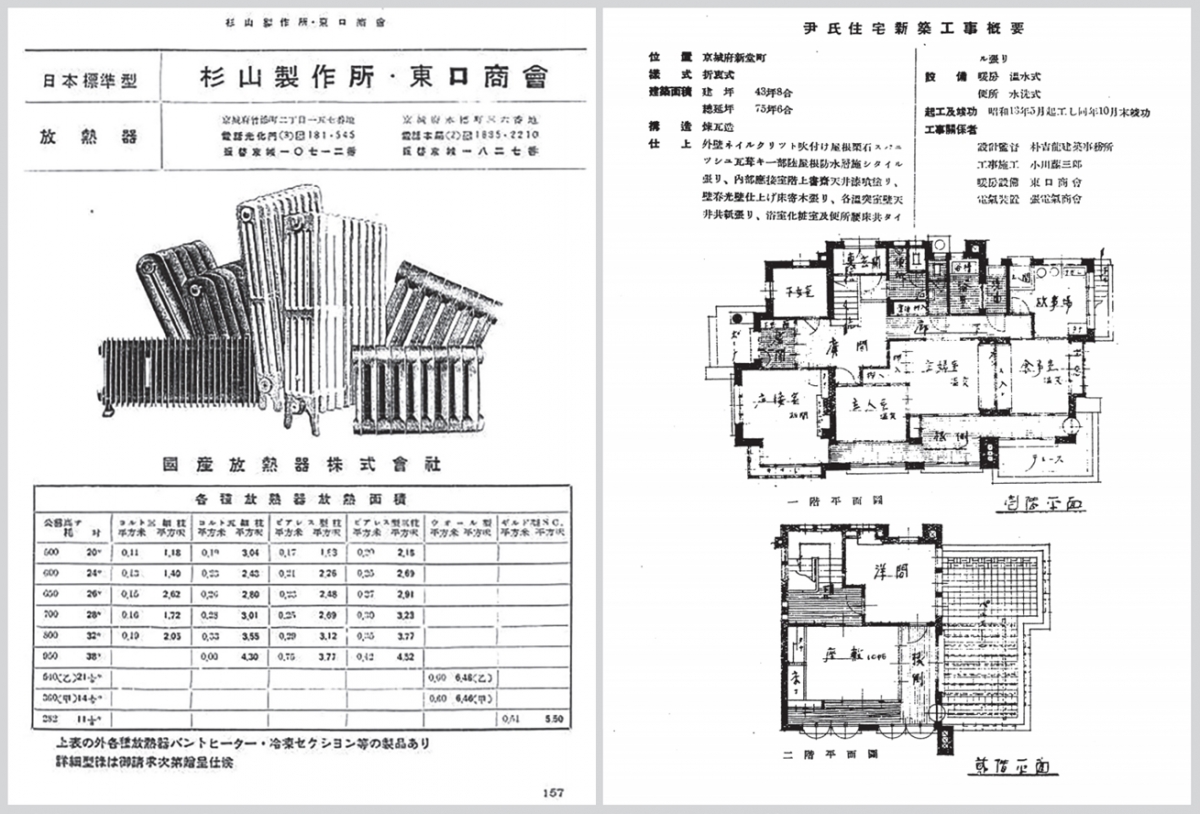

Second, let’s look at the heating system. Park Kilyong understood well the importance of the ondol in a hanok and kept trying to improve it. Initially, he tried to organise rooms around the kitchen and to bring fireplace (agungi) for the ondol together in the kitchen. However, this was not possible for a house with many rooms, so he addressed this issue in various ways. The most important solution was to build a basement and bring several fireplaces for the ondol together in one place. This aimed to improve the convenience of the circulation and the efficiency of heating. In particular, houses with a middle corridor had a basement below the middle corridor to concentrate the ondol fireplaces in the basement. This feature also appears in Pak No-soo House. Mr. Yun House in Sindang-dong was equipped with central heating system provided by the Donggu Hardware Store. The Building Material Catalogue, published by the Building Material Showcase of Architectural Association of Joseon in 1938,▼6 listed the central heating systems of the Donggu Hardware Store, which are very similar to the radiators used in Pak No-soo House. The radiators were also found to be similar to the radiators in Bohwagak, which underwent renovation recently. Therefore, it is very likely that both Bohwagak and Pak No-soo House were installed by the Donggu Hardware Store. Although all the boilers have now been removed, the radiators still remain in Pak No-soo House. There are eight metal radiators in total, one in the reception room on the ground floor, two in the hallway, one in the living room, one in the kitchen, one in the dining room, and one in the workshop and one in the bathroom on the second floor, all installed in wood frames.

What is worth noting is the fact that the master bedroom and children’s room on the first floor and two rooms in the basement are equipped with the ondol. Three ondol fireplaces are located in the basement for efficient ondol management. Currently, there is only one ondol fireplace that heats the floor of the basement room, but the other three have been removed. However, an ondol fireplace that heated another room in the basement appeared in the 2012 field survey report, suggesting that it was lost when the house was converted into an art museum.▼7

Moreover, according to interviews with Pak No-soo’s daughter, the fireplace in the master bedroom on the first floor had been installed in the wall of the basement briquette storage room, but disappeared when the wall was sealed with wood because of humidity.▼8 The other room by the front door had a fireplace through the exterior wall, which was also closed because it was not used. Each room has its own fireplace, and this is clearly evident in the chimneys rising from the roof of each room. This heating system is consistent with Park Kilyong’s usual opinions on adopting a Korean way of life in the style of Japanese style houses.▼9

The final attention needs to be paid to the building’s formal motifs and materials. A characteristic feature of the Pak No-soo House is the rafters protruding from the eaves under the sloping roof of Japanese tiles. They have a round cross-section, and seem to be a very Korean motif, because Japanese architecture uses square section rafters. This clearly shows that this building was designed by a Korean architect, not a Japanese one. The purlins supporting the rafters protruding from the side walls are also an important feature in the architecture. In terms of the roof form, the most comparable example can be found in Mr. Yun House in Sajik-dong. In Choie Soonai’s thesis, a dim photograph shows a similar sloping roof with purlins protruding below.▼10 In that sense, a clear connection with Pak No-soo House can be presented. Given the above three perspectives, it is almost certain that Pak No-soo House was designed by Park Kilyong. In particular, there is a strong connection with the Mr. Yun House in Sindang-dong, which was designed around the same time.

(clockwise) Section, left side elevation, second and first plans of Pak No-soo House (collections of the Seoul Museum of History

(left) Heating appliances in the Donggu Hardware Store (source: Architectural Association of Joseon, Building Material Catalogue, 1938, p. 157), (right) Plans for first and second floors of the Mr. Yun House in Sindang-dong (source: Joseon and Architecture, Mar. 1939)

1 The Establishment of Bohwagak and Active Collection, http://kansong.org/kansong/biography_4/ [accessed 18 Apr. 2023].

2 Shimizu Corporation, Architectural Drawing Collection of Houses, 1939, p. 119. Shimizu Corporation had already published the first volume in 1935, with the collection of housing projects constructed by his company. This is the second volume with the houses completed between July 1934 and June 1938.

3 It is not clearly known why they were named differently, but I think it's because the surname Min (閔) is transliterated as B (びん) in Japanese. In this article, the house will be credited as ‘Min Byeongsu House’.

4 Park Kilyong, ‘The Modern and Architecture: The Criticism of Famous Buildings in Gyeongseong,’ Dong-A Ilbo 1 Aug. 1936.

5 Park Kilyong, Joseon and Architecture (Mar. 1939), p. 72.

6 Building Material Showcase of Architectural Association of Joseon, Building Material Catalogue, 1938, p. 157. This was a catalogue of building materials that was originally displayed on the second floor of the Nippon Life Building and was published as a booklet for the convenience of local officials.

7 Report on the Precise Survey of Pak No-soo House in Okin-dong, Culture and Public Affairs Division, Jongno-gu Office, 2012, p. 95.

8 Author’s interview with Park Isun, 23 Feb. 2023.

9 Park Kilyong, ‘Popular, so called, Culture House,’ THE CHOSUNILBO 22 Sep. 1930.

10 Choie Soonai, A Study of the Life and Architecture of Park Kill Rong, Hongik University master’s thesis, 1981, p. 174.

You can see more information on the SPACE No. 667 (June 2023).