SPACE January 2024 (No. 674)

The Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale opened in 1995 and will celebrate its 30th anniversary in 2025. It opened as the last of Giardini’s national pavilions and has had a bumpy ride from its inception to the present day. This report looks back at the background and design concept of the Korea Pavilion and highlights the art and architecture exhibitions that have taken place in the space since its opening. Also, it will examine the meaning and possibilities of the Korean Pavilion and explore its future development, including the expansion and renovation currently under discussion.

View of the Korean Pavilion after construction ©Mancuso E Serena Architetti Associati / Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea

Aspirations for the National Pavilion

South Korea’s first participation in the Venice Biennale, which began in 1895, was in 1986. The Korean Pavilion, which did not have an independent country pavilion then, was allocated a part of the Italian Pavilion’s annexe and exhibited on several walls. The three editions in 1988, 1990 and 1993 were also held without a Korean national pavilion. Since the late 1980s, when Korean art began to expand overseas in earnest, the domestic art community has called for a national pavilion. Still, it had long since run out of space at the Giardini and several other countries, including China and Argentina, were waiting in the wings to build their pavilions. In 1993, Nam June Paik, who participated in the Biennale as an invited artist in the German Pavilion, won the Golden Lion Award and began actively engaging in exchanges with domestic and international cultural figures, harnessing their will and taking the lead in building the Korean Pavilion. He wrote a letter to the then mayor of Venice, arguing that the creation of a national pavilion that could be shared by both North and South Korea would be a way of bridging political tensions through art, which coincided with historical events such as the reunification of Germany in 1990 and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and was an important factor in obtaining permission to build the Korean Pavilion. This is evidenced by the fact that the top of the Korean Pavilion building reads ‘Corea’ rather than ‘Corea del Sud’ (South Korea) or ‘Repubblica di Corea’ (North Korea).

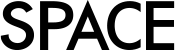

Kim Seok Chul and Franco Mancuso discussing the design plan for the Korean Pavilion with then Minister of Culture Lee Minseop ©Mancuso E Serena Architetti Associati / Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea

A Glass-and-Steel Structure That Blends into its Surroundings

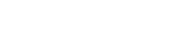

The designers of the Korean Pavilion, Kim Seok Chul (former principal, ARCHIBAN) and Franco Mancuso (former professor, Università Iuav di Venezia), initially proposed an underground national pavilion, given the lack of space in the Giardini. However, the plan was rejected as impossible due to the deep roots of the trees, and the Korean Pavilion was eventually built on the site of the administrative offices and toilets between the Japanese and German Pavilions. Given the condition that the existing vegetation and topography must not be disturbed, the two architects sought to overcome the limitations of the narrow site by using glass and metal as the primary materials. The existing brick building was retained, but cylindrical glass spaces were inserted to open the space to the outside, and the rooftop level was used as an exhibition space. Covering an area of 244m2 (ground contact area of 235m2) and a gross floor area of 249m2, the Korean Pavilion consists of three exhibition halls, each with a different structure and form, such as a cuboid, a cube, and a semicircle, which distinguishes it from the usual box-shaped exhibition space. This spatial feature of the Korean Pavilion has been criticised by artistic directors and artists (who have exhibited there since its opening) as weak for an exhibition space. However, as the experience of exhibiting in art and architecture exhibitions gradually accumulated, they began to accept the unique space of the Korean Pavilion as a given condition and to seek a way forward through various compositions and experiments.

Sketch of the Korean Pavilion in early stage ©Mancuso E Serena Architetti Associati / Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea

Model of the Korean Pavilion ©Mancuso E Serena Architetti Associati / Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea

Function as an Exhibition Space

Since 1995, the Korean Pavilion has hosted art and architecture exhibitions every other year, and as of 2023, a total of 14 art exhibitions and 13 architecture exhibitions have been held. Art critic Chung Joonmo, who visited the 1995 exhibition shortly after its opening, said, ‘The Korean Pavilion is a postmodernist building, an architectural phenomenon of the late 20th century, and if we ignore its primary function as an art exhibition hall, it has a unique structure both in appearance and architecture. [...] In the excitement of the opening of the Korean Pavilion, its function as an exhibition hall was treated as an afterthought, but it should be discussed once again’ (covered in SPACE No. 333).

In addition, artist Kim Inkyum, who participated in the exhibition in the same year, noted that he had to revise the installation plans because the semicircular space’s ceiling height was only 2.25m. Despite struggling with the unique exhibition space, the early exhibitions in the Korean Pavilion seem to have recognised the international art scene of the Venice Biennale as a new possibility and were primarily concerned with how to present the work of significant artists of the time.

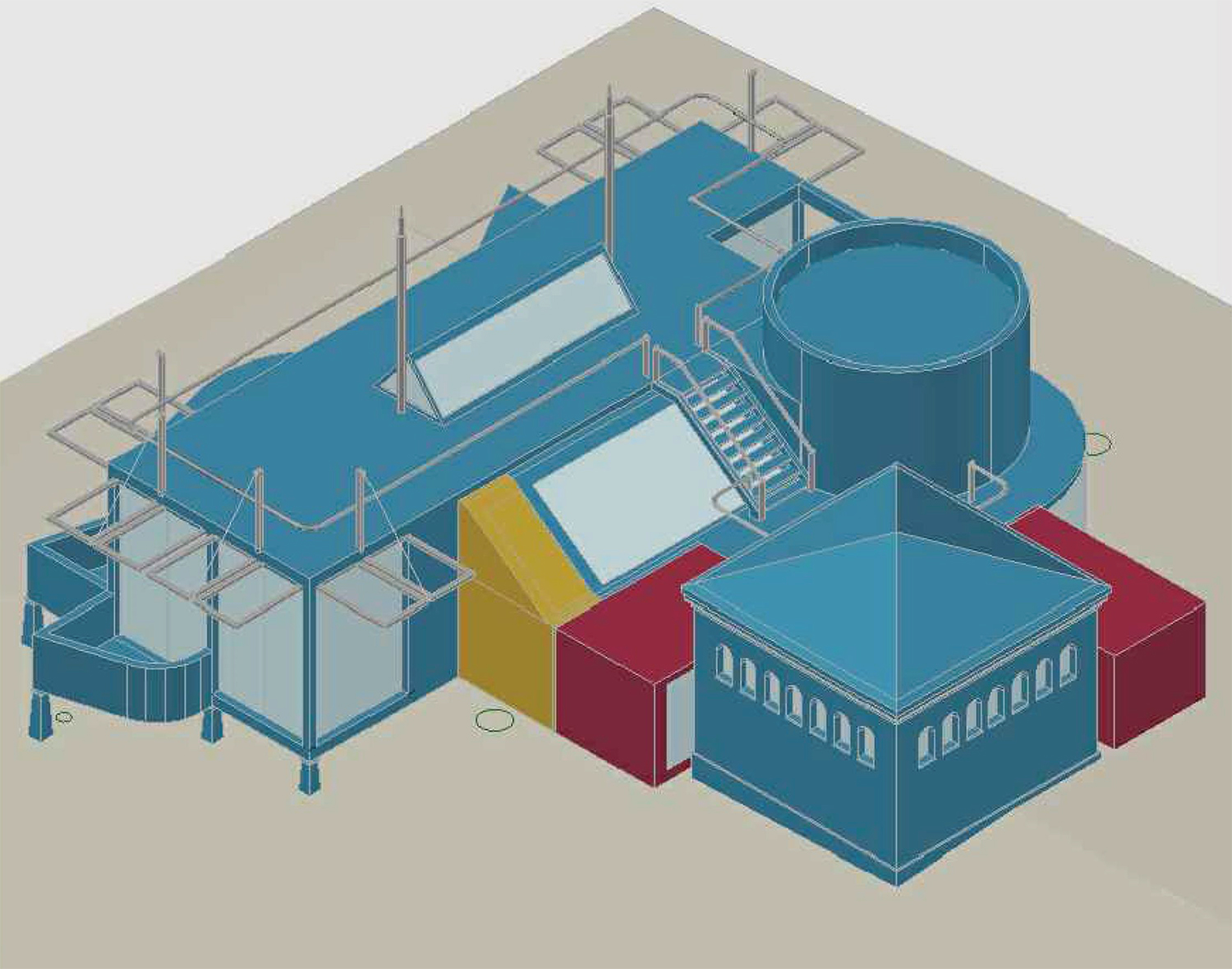

Expansion and renovation plan for the Korean Pavilion ©Mancuso E Serena Architetti Associati / Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea

Art Exhibitions Respond to Non-Linear Spaces

However, the 2003 exhibition led by Kim Honghee commissioner showed a different approach. As the title of the exhibition, ‘Landscape of Differences’, suggests, the planning of the exhibition began with the structural, spatial, and site-specific characteristics of the Korean Pavilion that make it different from other national pavilions and then sought to create further differences. While previous exhibitions used modifications to the interior structure, such as coating glass walls or erecting false walls to overcome the spatial limitations of the Korean Pavilion, this exhibition focused on building the identity of the Korean Pavilion by presenting new works that explored the architectural space of the building in its original state. On the other hand, the exhibition curated by Kim Sunjung (artistic director, Art Sonje Center) in 2005 was the largest exhibition of its kind in the Korean Pavilion, with 15 artists selected to showcase their works, as opposed to the previous exhibitions, which selected two to four artists and focused on their works, given the small space. Participating artists attempted to actively interpret the architectural space, with Choi Jeonghwa stacking red colanders on the roof of the Korean Pavilion to create a giant rampart and Park Kiwon wrapping the exterior walls in rounds of translucent fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) to actively interpret the building.

In 2013, commissioner Seungduk Kim selected Kimsooja as the sole artist for an exhibition that interpreted the physical space of the Korean Pavilion as a bottari. It covered the glass exterior walls with a translucent film, filling the empty space inside with only refracted light and sound in order to fully experience the space of the Korean Pavilion. The 2019 exhibition, led by independent curator Kim Hyunjin as artistic director, featured video installations by three female artists on the themes of post-colonisation and gender in a form that corresponded to the spatial characteristics of the Korean Pavilion. For this exhibition, a homecoming exhibition was held at the ARKO Art Center, and in an interview, Kim Hyunjin said, ‘We didn’t get to do it in the home exhibition, but in the main one all the monitors were human scale. It was a space that used to be a toilet, so the exhibition was set up in a square shape with both wings parallel to each other. I wanted the audience to feel like they were part of the performance happening the moment they walked into that room. [...] The spatial limitations at the ARKO Art Center make it challenging to give the audience a sense of being part of the performance, like at the Venice Biennale.’▼1 In this way, the art world, initially reluctant to use exhibition spaces other than a generic white cube, seems, through repeated exhibitions, to have found a way to accept and overcome the limitations.

Architectural Exhibitions Built on Limitations

In the early years of the exhibition, since there was no established discourse or methodology for ‘architecture exhibitions’, they were limited to introducing architectural works in Korea through models or panels. Led by commissioners Kang Suk Won in 1996, Kim Seok Chul in 2000, and Kimm Jong-Soung in 2002, the exhibition focused on the work of young architects looking ahead to the architecture of post-unification Korea, with the expectation that the country would be reunified within a decade. Meanwhile, the exhibition curated by Chung Guyon in 2004 was no longer limited to presenting domestic architectural works, but, under the theme of ‘City of the Bang’, participating artists Kim Kwangsoo (principal, studio_K_works), Song Jaeho, and Yook Seokyeon (professor, University of Seoul) presented new works that interpreted Korean urban culture such as Norae bang (karaoke), Jjimjil bang (Korean dry sauna), and PC bang. The exploration of this urban phenomenon continued in a 2006 exhibition directed by Joh Sungyong (principal, johsungyong architect office/ubac). The five participating architects, Kim Seunghoy (principal, KYWC Architects), Kim Chanjoong (THE_SYSTEM LAB), Kim Hun (principal, studio asylum), Shin Haewon (principal, lokaldesign), and Choi Wook (principal, ONE O ONE architects), exhibited their observations and interpretations of the urban situation in Korea, represented by Seoul. In an interview during the exhibition, Choi Wook said, ‘The spatial features of the Korean Pavilion and the reality of the exhibition preparation process seem to align with the situation we usually face in Seoul. There are national pavilions that are very well curated. However, this is not the case with the Korean Pavilion, so an aesthetic phenomenon needed to be created. I think it’s a matter of overcoming the difference between a situation not subject to criticism and the conditions of reality’ (covered in SPACE No. 467). Similar to the attitude of architecture, in the case of architectural exhibitions, they accepted the space of the Korea Pavilion as a given condition and situation, and gradually tried to create a differentiated composition by establishing a curatorial method.

The exhibition ‘Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula’, curated by Cho Minsuk (principal, MASS STUDIES), who was selected as a commissioner in 2014, with Pai Hyungmin (professor, University of Seoul) and Ahn Changmo (professor, Kyonggi University) as curators, won the Golden Lion Award and signalled a significant trajectory in the exhibition history of the Korean Pavilion. The meaning of this show can be discussed from many angles, including the curating method, but if we look only at the formal aspect, it overcomes the spatial inferiority of the Korean Pavilion by arranging the works of 29 participating artists within the overall structure under the theme of South and North Korean architecture and finding a strategic balance (covered in SPACE No. 560). Since then, Sung Hong Kim (professor, University of Seoul) in 2016, Park Seongtae (core value leading officer, Junglim Foundation) in 2018, Shin Haewon in 2021, and Jung Soik (principal, Urban Mediation Project) and Park Kyong (professor, University of San Diego) in 2023 have been the artistic directors, presenting exhibitions with different themes as an extension of contemporary Korean architectural discourse and continuing to experiment with architecture exhibitions in the Korean Pavilion (covered in SPACE No. 669).

The layout of the Korean Pavilion that does not conflict with existing trees and terrain ©Mancuso E Serena Architetti Associati / Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea

Extension and the Challenges Ahead

As we have seen so far, the Korean Pavilion is approaching its 30th anniversary while experiencing many twists and turns. It is a significant achievement that the Korean Pavilion has managed to overcome its spatial limitations through various exhibition experiences. However, at this point, quite some time after the completion of the Korean Pavilion, in addition to the special spatial characteristics, there is a maintenance issue that needs to be solved. Due to the age of the building and the nature of the biennale, which attempts to create a new space for each exhibition, it was time for a renovation. It was also pointed out that the space needed to be bigger for exhibitions, and there was no space to store exhibition equipment or room for other facilities.

The Arts Council Korea, which operates the Korean Pavilion, announced plans to expand the Korean Pavilion in 2018 in response to these needs. Since the co-designer Kim Seok Chul passed away in 2016, Franco Mancuso took the lead in designing the expansion plan. According to the city of Venice’s detailed urban plan, large-scale expansion was impossible, so plans are in the works for a 28m2 extension that will increase office and warehouse space, which is currently inadequate, and connect the exhibition space. On the 25th of October, 2023, at a roundtable on ‘The Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale: Current Issues and Possibilities for Designing a New Future’ held at the ARKO Art Center, Arts Council Korea presented the status of the expansion and renovation project (covered in SPACE No. 673). According to the organisation, in September 2018, it applied for planning approval from the City of Venice’s City Hall Department, but since the proposed expansion does not comply with the current enforcement law, the city council will have to amend the city law before it can be passed.

At a public hearing organised by the Arts Council Korea on the 30th of November, 2023 to explore the direction of the Korean Pavilion, Lim Keunhye (director, ARKO Art Center) said that she would continue to work towards the approval of the expansion plan until 2025 and that she would also reorganise and strengthen her role as commissioner with the tasks of securing funding, constructing an archive and revitalising the museum. As mentioned, the future of the Korean Pavilion is about more than just improving the space. It is only when we take stock of the progress of the Korean Pavilion over the past 30 years on the international stage of the Venice Biennale and improve the institutional aspects of its operation and execution that we can then discuss the next steps for it.

Interior view of the Korean Pavilion ©Mancuso E Serena Architetti Associati / Image courtesy of Arts Council Korea

1. Shin Jiye, ‘Korea’s representative feminist artist Jeong Eunyoung, “History has failed us, but no matter”’, The Women’s News, 13 June 2020.