SPACE February 2024 (No. 675)

Rapid population decline is shaking the fabric of small and medium-sized cities to the core. To rebuild these cities, we need to move away from the inertia of regeneration and take a perspective that acknowledging change. This is where the Mid-Size City Forum comes in. They look at phenomena outside the metropolitan area and seek urban and architectural alternatives to the crisis.

[Series] The Possibilities Inherent in Extinction, Mid-Size City Forum

01 What is Happening Outside the Metropolitan Area

02 Thinning Phenomenon

03 Urban Perforation

04 Erasing Plan

05 Ad-hoc Architecture

06 Global Mid-Size City

07 Resilient Mid-Size City

08 Fantastic Mid-Size City

09 Outside of the Mid-Size City

The provinces are disappearing. The statistics clearly anticipate it. In the face of this crisis, small and medium-sized (hereinafter mid-size) cities are displaying markedly different signs of change than large cities. The Mid-Size City Forum says it is time for the urban and architectural community to recognise the problems with the status quo and begin to look for alternatives. Starting with this issue, SPACE will be doing a bi-monthly examination of the mid-size cities they have discovered. From that starting point, Mid-Size City Forum will outline the story as it unfolds.

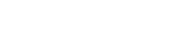

The population decline and aging in mid-size cities (1975 – 2022). The population of mid-size cities will continue to decline in the future unless there is an additional influx of people.

New Realities

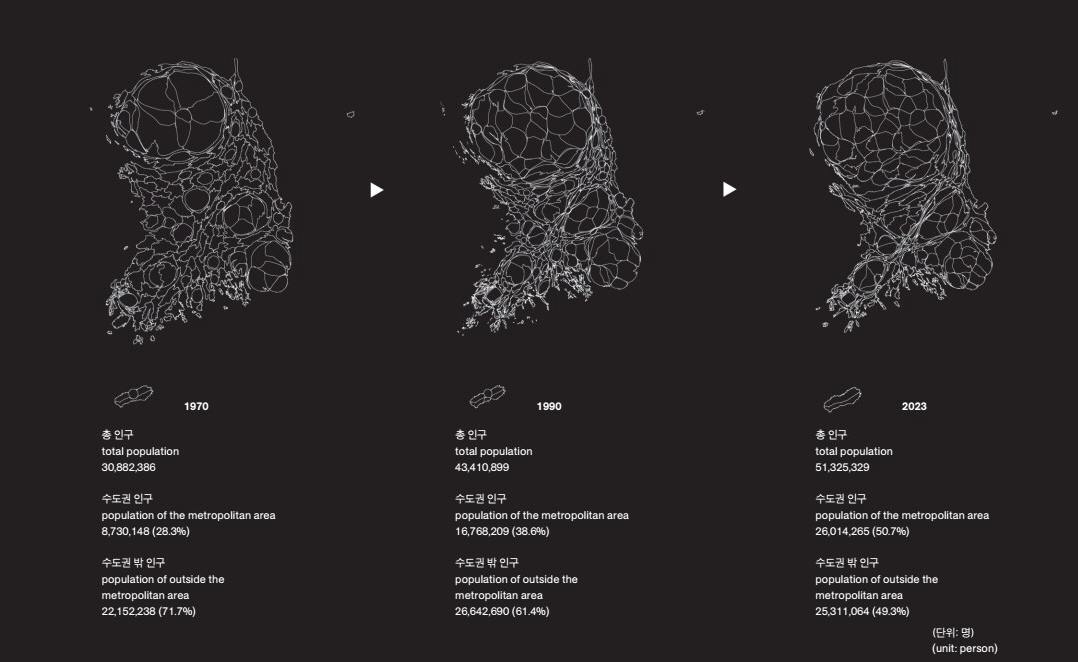

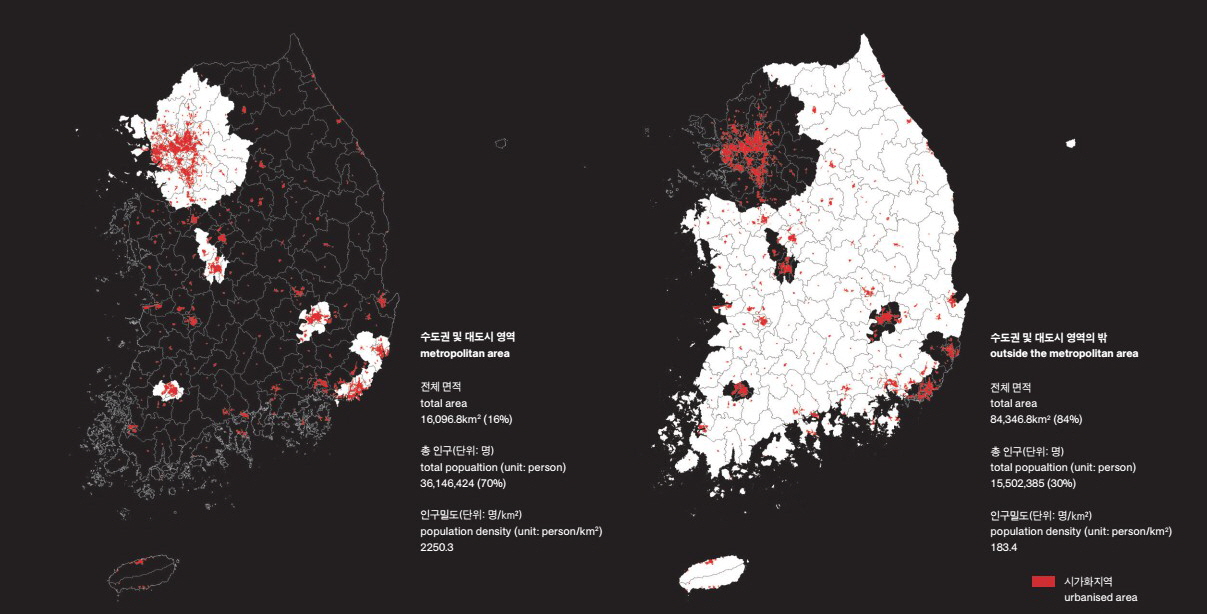

The Five-Year Economic Development Plans that began in the 1960s and the subsequent state-led process of industrialisation rapidly reshaped the country from a rural to an urban-oriented system. In particular, the change from an agricultural-based economy to an industrial-based one led to the concentration of population in cities, meaning that cities expanded swiftly by absorbing the population outside the city. Since the 1990s, the transition to a neoliberal system in line with globalisation, the deregulation of the metropolitan area and changes in industrial policy since the 2000s, and the reorganisation of the national transport network through the opening of high-speed railways and the expansion of highways have led to a renewed focus on the national economy. As a result, about 50% of Korea’s current population is concentrated in the metropolitan area, which covers 11.8% of the country’s land area.

In 2024, we are facing another massive wave of change, caused by rapidly declining birthrates, an ageing population, and the resulting population decline. Currently, Korea’s total fertility rate is at an all-time low of 0.7, and the country has entered a super-aged society stage, with about 18% of the population aged 65 or older. If the current low birth rate continues, it is predicted that in 20 years, about 37% of Korea’s population will be 65 or older, and the total population will decrease by more than 2.33 million. Despite this rapid change in demographic composition, the current industrial and demographic structure, which has been reorganised around the metropolitan area, makes the metropolitan area relatively immune to this phenomenon. However, the situation outside the metropolitan area is in stark contrast. Here, rapid population decline is disrupting the existing urban fabric, building types, programmes, transport systems and industrial structures.

Statistics show that the majority of mid-size cities outside the metropolitan area are experiencing rapid population decline, including Sangju, Jecheon, Jeongeup, Gimje, Namwon, Naju, Boryeong, Miryang, Sacheon, Gongju, Yeongju, Mungyeong, Nonsan, Taebaek, and Samcheok. In Namwon, Jeollabuk-do, for example, the city’s population reached about 175,000 by 1975 but now stands at 77,000, representing a decline of about 57% in the last 50 years. Over the same period, Sangju, Gyeonsangbuk-do, decreased by about 59%; Gyeongju, Gyeonsangbuk-do, by about 58%; Miryang, Gyeongsangnam-do, by about 43%; Taebaek, Gangwon-do, by about 67%; Naju, Jeollanam-do, by about 47%; and Nonsan, Chungcheongnam-do, by about 46% (refer to p. 125). In addition, these cities are also experiencing an ageing population. In Namwon, Jeollabuk-do, about 41% of the population is 60 and over. And other cities have similar proportions of the elderly population. Therefore, it is expected that the population of these cities will continue to decline in the future unless there is an additional influx of people.

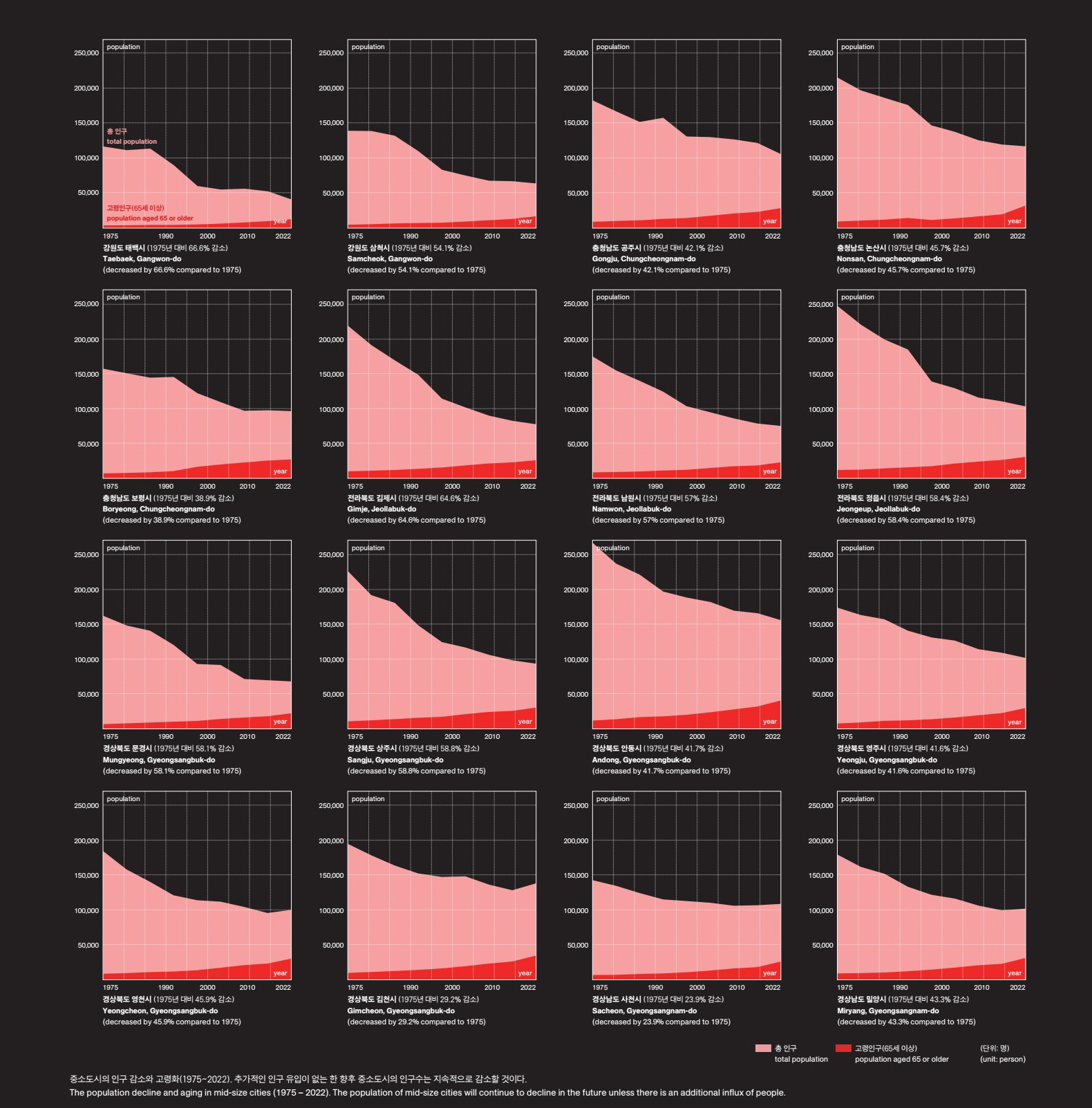

Changes in the proportion of the population in cities outside the metropolitan areas. While the natural growth rate is negative, the sum of the proportion of the elderly and the foreign population is increasing.

Another Model

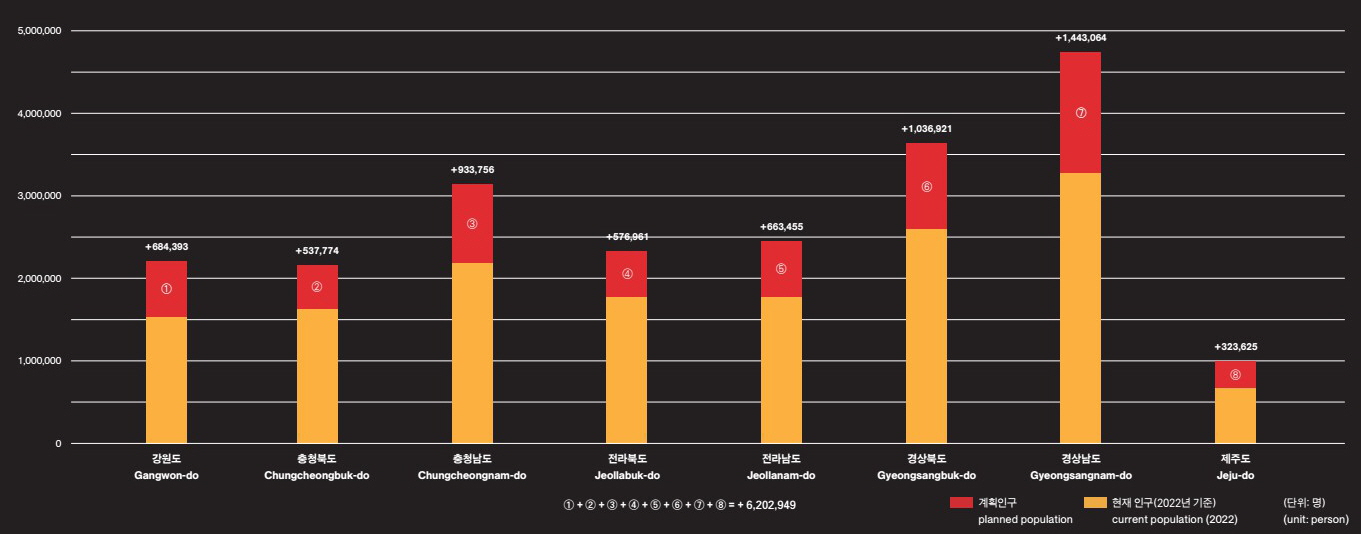

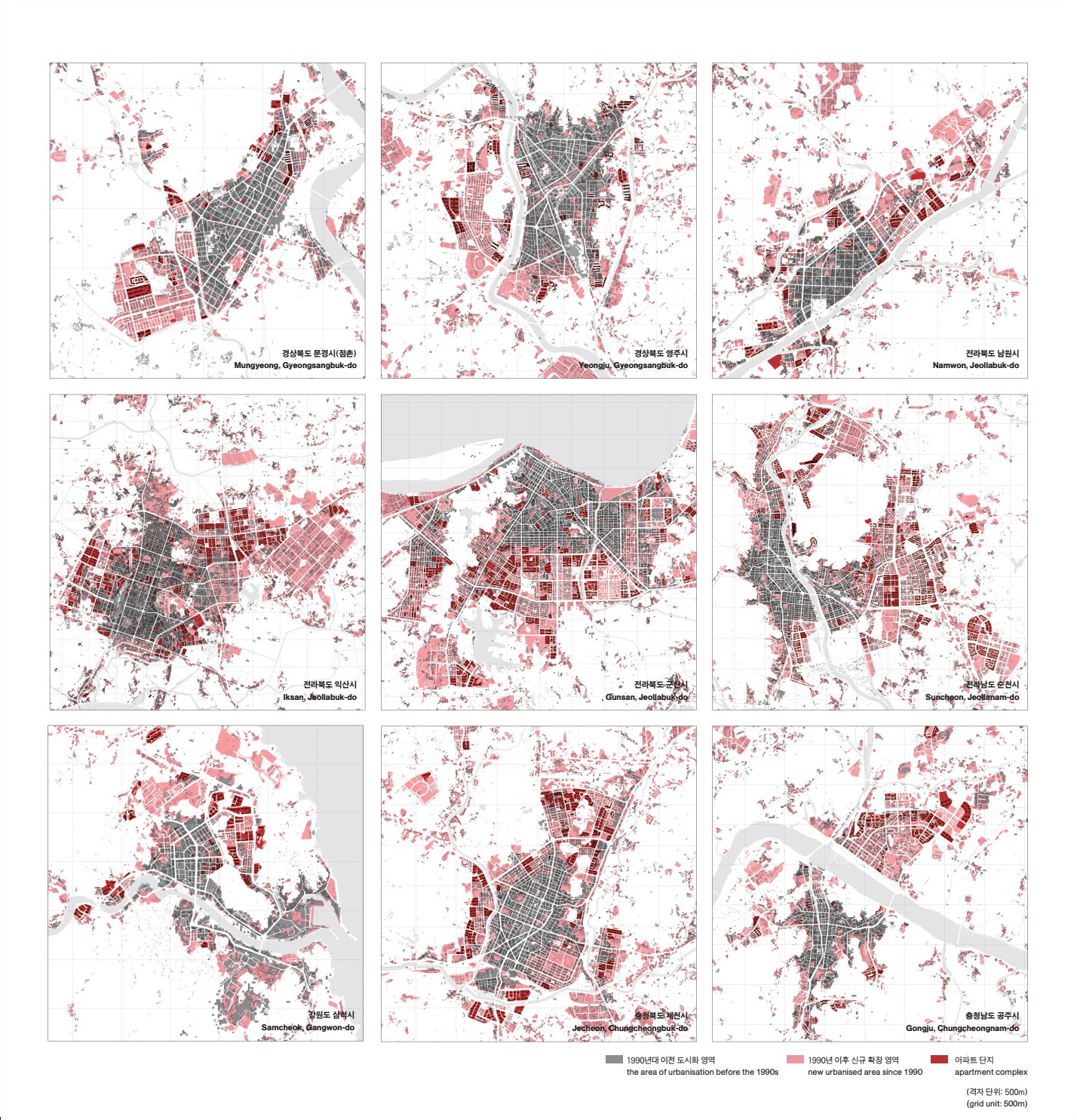

Despite this prediction for the future, many policies are still designed within the paradigm of the population growth needed to revitalise areas. Let’s explore future population projections for municipalities across the country. It is assumed that the population will continue to grow for the next 20 to 30 years. For example, in Gyeongsangnam-do, the planned population is assumed to increase by 1.44 million people, while Gyeongsangbuk-do is supposed to increase by 1.04 million; Chungcheongbuk-do by 540,000; Chungcheongnam-do by 930,000; Jeollanam-do by 660,000; Jeollabuk-do by 580,000; Gangwon-do by 690,000; and Jeju-do by 320,000. Adding these population projections together results in an increase of approximately 6.2 million people outside the metropolitan area in the next 20 to 30 years (refer to p. 129). These population projections are a vital factor in determining the future of mid-size cities, as they form the basis of local governments’ medium- and long-term urban planning. From these population projections, many mid-size cities have planned large-scale apartment complexes on the outskirts of the town through new land development since the 1990s. To this day, however, much of the area remains undeveloped, and local residents use many of the plots as makeshift gardens.

It is time to face up to the current situation of the declining population and start thinking about alternative models for dealing with it. It requires specific research on the impacts of demographic shifts. Outside of metropolitan areas, the population decline is driving change in a completely different direction than what we typically experience in large cities. With the exodus of young workers and the rapid ageing of cities, young foreign workers and automated machinery are filling the vacancy. In addition, as population concentrations within cities become thinner, the street vitality found in metropolises disappears, and it becomes the norm that each person owns a car as existing public transport systems are beyond capacity. Furthermore, because development pressure is low, the opposite of development pressure is at work: decay pressure, as deteriorating buildings are no longer naturally linked to the reconstruction process. Rather than the urbanisation paradigm of concentrated and dense populations, these changes are more of an anti-urbanisation paradigm.

The population changes of the metropolitan area and outside the metropolitan area (1970 – 2020).

How to Look at It

The Mid-Size City Forum is interested in how these changes occur outside the metropolitan areas and the variations they bring. And we pay attention to the new possibilities they create. Also, we will focus on its potential rather than critically examining its current state of change. Through this, we hope to find an alternative urban and architectural language by discovering and redefining things that exist in reality but that we need to be made aware of. In a future series, we will discuss changes outside the metropolitan area. We want to talk specifically about what is happening outside the metropolitan area, how these aspects can be read, what patterns they unfold, and how they can be reconstructed into an urban-architectural language.

The eight topics we will be talking about are as follows: The first topic concerns the phenomenon of ‘thinning phenomenon’, the thinning of population density in cities. Since the 1990s, mid-size cities have experienced a quantitative expansion in urban areas through large-scale new housing developments. The expansion of urban areas, coupled with the subsequent population decline, results in a thinning of population density across the city. We will discuss how this phenomenon is changing the way of life in mid-size cities.

The second topic is the ‘perforation’ phenomenon in mid-size cities. The decline in population in mid-size cities goes beyond the phenomenon of vacant houses to the phenomenon of perforation, whereby empty houses are demolished, creating holes in the urban space. This is happening in most mid-size cities, where declining populations are creating decay pressure, which is likely to accelerate given future population projections. We look at the patterns of perforation and the consequences for urban space in the old town.

The third topic is about ‘erasing plans’ that use decay pressure. If we can use perforation, which occurs in mid-size cities due to decay pressures, as a planning tool, we can design a new urban model completely different from previous urban forms. Erasing plan is a methodology that reverses the traditional urban planning grammar of creating a city, planning where to erase rather than where to build. We will explore the possibilities of a new urban model through these erasing plans and the detailed strategies to achieve it.

The planned and current population of major mid-size cities with a population of 50,000 to 200,000

The planned and current population of regional local government, excluding the metropolitan area. Adding these population projections together results in an increase of approximately 6.2 million people outside the metropolitan area in the next 20 to 30 years.

The fourth topic is ‘ad-hoc architecture’, which is prevalent in mid-size cities. Mid-size cities have lower development pressure, so as buildings age, they extend the life of older buildings by adding to them rather than tearing them down and building new ones. It is not just a unique phenomenon in one or two cities; it is happening all over the country simultaneously and at a breakneck pace. Noting the recurrence of this phenomenon, we examine the elemental characteristics of ad-hoc architecture and its potential as an urban typology.

Landscape of mid-size city streets with exotic shops and signs. Foreign workers are filling the labour force gap in mid-size cities.

The fifth is ‘heterogeneity’. A rapidly shrinking and ageing population is creating a labour force gap in the region, which young foreign workers are filling. And their rise in number is changing the streetscapes of mid-size cities. When you visit a mid-size city, it is not uncommon to run into foreigners on the streets, and you will be confronted with a landscape of exotic shops and signs. We will explore the transnational landscape of mid-size cities and the new possibilities it holds for declining cities.

The sixth theme is ‘resilience’. Mid-size cities that rely on industries that generate large influxes of people, such as tourism, can experience an influx of out-of-towners that is often dozens of times greater than the resident population at any given time. These cities are only active at certain times of the year and remain inactive at other times, requiring flexible programming to accommodate the influx of outside populations. We look at some unconventional operational strategies these cities use to cope with their peak-time workforce.

The seventh theme is ‘B-list mid-size cities’ that are parasites in larger cities. Some smaller cities define their role in relation to their parent city. These cities attract a variety of small industries and subcultures based on their economic comparative advantages over their parent cities, such as lower cost of living, lower rents, and better value for money. These include roadside outlet malls, secondary and tertiary contract factories, unattended motels, entertainment venues, and shantytowns to keep the city alive. We look at how these B-list mid-size cities are changing the character of their towns as they form relationships with their parent cities to urvive.

The final topic is about the ‘countryside’ outside the mid-size cities. It is witnessing radical changes on a different level than mid-size cities. Rural areas are becoming more sparsely populated and are rapidly becoming more mechanised and automated, requiring less human touch. As a result, the countryside is being transformed into a landscape of massive solar panels, giant logistics centres and automated greenhouses. We look at the phenomena of rural areas becoming unmanned and the new possibilities this offers.

Throughout these eight topics, We will describe what is happening outside the metropolitan area. However, this vast area, which covers 88.2% of the country’s land area, will have many other issues. The Mid-Size City Forum will continue to observe various phenomena outside of metropolitan areas and regions, discover new possibilities, and consider alternative models for utilising them.

The new housing development in mid-size cities since the 1990s. It stems from predictions that the population will increase, however, much of the area remains undeveloped.