SPACE March 2024 (No. 676)

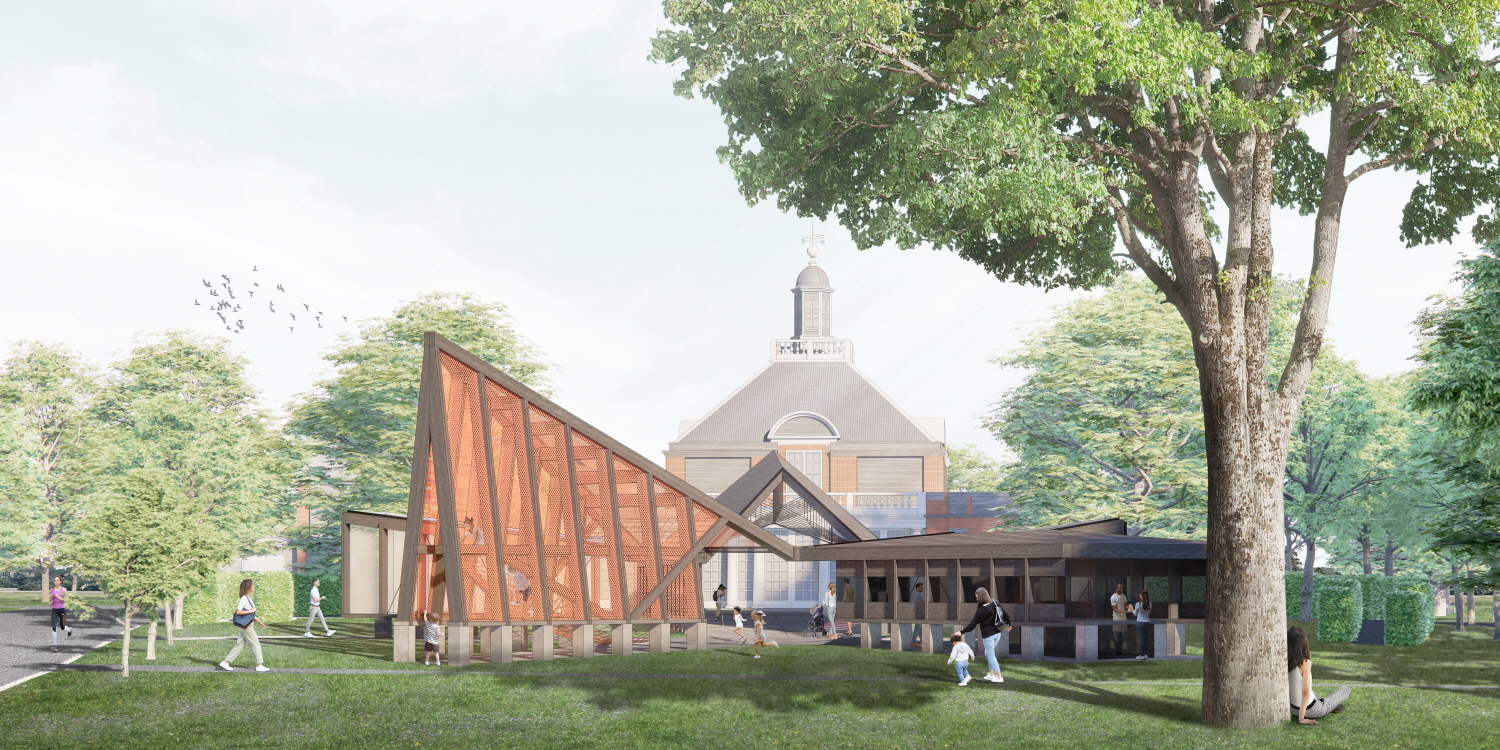

Rendering image of exterior view, Archipelagic Void(2024) ⓒMASS STUDIES / Image courtesy of Serpentine

DIALOGUE Park Junghyun architectural critic × Cho Minsuk principal, MASS STUDIES × John Hong professor, Seoul National University

Starting the Dialogue: The Pavilion and the Anti-Pavilion

In spite of the fact that the projects of MASS STUDIES (principal, Cho Minsuk) have evolved to include a diverse range of programmes and scales since Cho Minsuk founded the firm over two decades ago, framing their recent work around the seemingly rudimentary term ‘pavilion’ is an important conceptual exercise. The generative principles within the projects presented in this issue’s FRAME reference a new definition of the term. Whereas the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a ‘pavilion’ as ‘a usually open sometimes ornamental structure in a garden, park, or place of recreation that is used for entertainment or shelter,’ an architectural pavilion carries a greater theoretical weight. This is because in architectural discourse, the pavilion becomes a proto-definition of what architecture can be―signifying architecture’s latent potential. In this way, a pavilion’s task is to embody and test architectural manifestoes, emerging technologies, and new socio-cultural conditions.

Take for instance Bruno Taut’s Glass Pavilion from 1914: the prismatic glass dome for the Cologne Werkbund Exhibition was not only a tectonic and technological meditation on new forms of glass use, it was also a utopian expressionist statement calling on the arts and architecture to transcend function and instead provoke spiritual freedom. If we are to look at the history of architectural pavilions since, they all carry this emergent role of capturing an architectural statement. And just as Bruno Taut’s Glass Pavilion was destroyed soon after the exhibition, it remains his most known work because it encapsulates the most distilled vision of his thinking.

Following this line of questioning, to what extent is Cho’s version of the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion (hereinafter Serpentine Pavilion), named ‘Archipelagic Void’, a statement of his architectural ideas? Here we must pause to examine what Cho’s pavilion is not. It is not an object. The overwhelming pressure of the architectural pavilion to define a spatial-tectonic manifesto typically compresses it into a thing: Just as Bruno Taut literally and metaphorically crystallised his thinking so that it clearly communicated his concept, the history of architectural pavilions, including those built for the Serpentine Gallery, is also marked by attempts to distil and declare authorship-of-concept into a singular vessel.

‘Archipelago’ and ‘void’ however are the opposite of ‘singularity’ and ‘thingness’. By creating a pavilion along these conceptual lines, Cho is in essence creating an ‘anti-pavilion’. Moreover, the anti-object quality of Archipelagic Void is both physical-present and conceptual-temporal. In terms of the latter, it is a layered space that takes into account the history of the Serpentine Pavilion as a means of cultural production. Instead of a statement ending in the creation of a filled centre, Archipelagic Void is a process that emanates from an emptied centre. Its void is contingent with space and time: it is pregnant with the activities that have and will inhabit it and the built manifesto-centres that preceded and will proceed it. In terms of the former, the pavilion’s physical-present qualities can be defined by its archipelagic status as a series of five different pavilion(s), non-hierarchically presented. The forms resist becoming an amalgamated object in favour of harbouring more spatial field-like qualities: circulatory flow, diverse use, and relations to surrounding context are all simultaneously integrated. The spaces inside of it are as important as the spaces defined outside.

Fortunately, the generosity of the term ‘pavilion’, as a vehicle for emerging concepts, also allows the existence of anti-pavilions. Just as the words ‘thesis’ and ‘antithesis’ are two equally important sides of the same coin, the role of the ‘anti-pavilion’ is to inject important ideas into the stream of architectural discourse to question and destabilise the status quo―steps necessary for the evolution of ideas. How then do we see Cho’s ‘anti-pavilion’ concept embodied in this recent work? In the following conversation, we hope to capture how the conceptual spectrum of the Archipelagic Void extends through other individual projects. written by John Hong