SPACE March 2024 (No. 676)

Quiet, high-walled residential neighbourhoods, the town where politicians live, and side streets with fancy cafés and eateries: various interests and different generations have diverse impressions of Yeonhui-dong, but its landscape and continuing transformation are attractive amidst the rise and fall of Seoul’s other neighbourhoods. Especially when the renovation of old houses is in the spotlight, and the diversity of urban architecture types is lacking, the landscape of neighbourhoods that are changing spontaneously, as the public changes, has implications for urban architecture. SPACE spoke with Kim Jongseok and Hong Jooseok, who have worked on several projects in Yeonhui-dong, as well as Yoon Seunghyun and Lee Jinoh who have lived and worked in the area for many years, and Jeon Sangkyu who has worked on small commercial buildings such as multi-family housing and neighbourhood living facilities, but has no direct connection to the district.

©Kim Yongsoon

SPACE × Kim Jongseok principal, COOM Partners × Yoon Seunghyun professor, Chung-Ang University × Lee Jinoh principal, Architects Office The SAAI × Jeon Sangkyu principal, Office for Ordinary Architecture × Hong Jooseok principal, URBANPLAY

How the Landscape of Yeonhui-dong Was Shaped

Kim Jeoungeun: Yeonhui-dong is a neighbourhood of single houses in the Yeonhui Land Compartmentalization And Rearrangement Project area, which began in the late 1960s. As you go deeper into the block, there are still many so-called ‘French-style houses’ built in the 1970s, maintaining the unique landscape of Yeonhui-dong, which has been changing over the past decade as these houses have been renovated into commercial spaces. What are your impressions of the neighbourhood?

Jeon Sangkyu: After a long time working in demanding, fastidious towns, I visited Yeonhui-dong and was impressed by the neighbourhood’s gradual, humane, flexible transformation. Compared to Yeoksam-dong, Nonhyeon-dong, and Segok-dong, which are residential areas developed in the 1970s that my office mainly works on, Yeonhui-dong seems to have a gently sloping terrain that is primarily flat, and road widths that are comfortable for traffic, which are the basic foundation for accommodating self-sustaining development.

Yoon Seunghyun: It is probably due to the geographical characteristics of the basin. On the east side, it is enclosed by Yonsei University, followed by Inwangsan Mountain, and to the northwest, it is bound by small Ansan Mountain and Gungdongsan Mountain. So, it could have maintained a single identity.

Kim Jongseok: The Yeonhui-dong area is zoned as a Class l exclusive residential area and a Class l general residential area, so it is naturally a town of low buildings, which has maintained its current tranquil appearance. The coexistence of old houses and new buildings creates a more enjoyable urban architectural landscape.

Hong Jooseok: The conditions of the Class l exclusive residential area, such as ‘a building to land ratio of 50% or less and a floor area ratio of 100% or less’, seem to be a decisive factor in slowing down the change in Yeonhui-dong, as they make it difficult for general contractors and developers to make a profit.

Yoon Seunghyun: Another characteristic is the size of the plots. Donggyo-dong, Seogyo-dong, Yeonnam-dong, Hapjeong-dong and Mangwon-dong are neighbourhoods built as new towns after the Korean War in the 1950s. At that time, most plots were divided into 40-pyeong (about 132m2) for small plots and 60-pyeong (about 198m2) for large plots, because it was a popular area for high-income workers who commuted to the city due to its good traffic system and proximity to the Sinchon area. The development of Yeonhui-dong in the 1970s began to subdivide the plots into 100-pyeong (about 330m2) units. I lived in Donggyo-dong and Seogyo-dong as a child, and many of my primary and secondary school friends moved to Gangnam. As the economy grew, life became more prosperous, and the desired residential area became larger. However, this was difficult to solve in Seogyo-dong and Donggyo-dong, where the lots were small. That’s why they moved to Apgujeong-dong and Nonhyeon-dong in Gangnam-gu, and Bangbae-dong in Seocho-gu. On the other hand, people living in Yeonhui-dong have no reason to move. So, more than half of Yeonhui-dong residents have lived there for nearly 40 years.

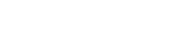

130-13 Yeonhui-dong is the first of 76 buildings planned, built or designed by COOM Partners. Currently, a radius of around 500m within a ten-minute walk of the café street on Yeonhui-ro 11ga-gil has been developed into a commercial area with a good distribution of commercial facilities. ©Kim Yongsoon

©Lee Hanul

124-31 Yeonhui-dong. It was tried to capture the form of an old village in a single building. It created alley-like pathways within the building and laid out courtyards that could be shared by multiple houses and connected organically. ©Lee Hanul

124-31 Yeonhui-dong. To remove psychological barriers, gates and fences were removed as much as possible, and accessibility from the street was increased. Terraces, staircases, and bridges open up internal and external views, allowing anyone walking by to experience the space. ©Lee Hanul

Opportunities Created by Residents’ Lifestyles and Low Property Values

Kim Jeoungeun: If you compare the average age of residents in Yeonhui-dong to other neighbourhoods in Seoul, you’ll find a high proportion of people in their 20s and 70s and older. It is likely due to their lifestyle.

Hong Jooseok: Since the 1970s, the residents of Yeonhui-dong’s 330 – 500m2 lot’s single houses have been well-off. However, maintaining a single house for so long (in Korea, where many live in apartments) means having a unique lifestyle. Quite a few creatives and artists say, ‘I can’t live in an apartment.’ This lifestyle eventually shaped the character of the commercial district. People prefer good local brands to franchises and shop at SARUGA Shopping Center (opened in 1975) instead of supermarkets. This culture has been the foundation for the continued creation of good local brands in Yeonhui-dong.

Lee Jinoh: Yeonhui-dong seems to have a positive specificity where old memories are retained in the urban fabric. It may be because the balance between residential and commercial areas is maintained. This is because, ironically, there has been no real estate boom for a long time.

Yoon Seunghyun: In other words, only some people would have bought a house in Yeonhui-dong solely for its investment value. People still don’t value Yeonhui-dong by property value. That’s what created the opportunity. A few years ago, Bart Reuser (founding partner, Next Architects) came to University of Seoul as a visiting professor and wrote a short book PLANNING SEOULUTIONS FROM HONGDAE after experiencing the area around Hongik University (hereinafter Hongdae). He felt that European cities had lost their liveliness because they looked the same after 10 to 20 years, but he was shocked to see Hongdae changing daily. ‘The Korean planning system moreover perceives owner-occupants as entrepreneurs who are invited to seek new opportunities with their real estate, instead of residents that need to be protected against unforeseen changes,’ he premises. He goes on, ‘some may call it a mess for lack of architectural cohesiveness,’ and he explains the fascination of Hongdae’s transformation by noting that residents with an entrepreneurial mindset have gradually adapted their buildings to meet new demands, ‘This gradual change has led to a great variety of materials used and a diverse and walkable district with a fine grain.’ Yeonhui-dong can also be seen from that perspective.

Lee Jinoh: Yeonhui-dong has a large plot of land and didn’t fill the floor area ratio when it was first built, so there’s no need to play the floor area ratio game now. That’s why we could build not only vertical extensions but also annexes and connect them. And because it’s a bit of a hilly site, there are still basements and strata that are less developed. So, within that space, COOM Partners and URBANPLAY have played an ongoing role in maintaining a mixed residential and commercial village with the memory of the urban structure through appropriate expansion, transformation of the houses, and relocation of the programme. In that sense, there is a point to looking more closely.

Kim Jeoungeun: COOM Partners has been involved in transforming 76 existing houses only in Yeonhui-dong. How did it all start?

Kim Jongseok: Of the 76 buildings planned, constructed or designed by COOM Partners, about 50 are currently clustered around the café street on Yeonhui-ro 11ga-gil. In 2009, we decided to quickly transform the central business district, which was the first place people saw when they began moving in, by leasing buildings owned by residents for ten years, fixing and managing them ourselves, and renting them back to artists, tenants, and good local brands. After about a year and a half of renovating and operating about ten houses in Yeonhui-dong alone by attracting investment from outside, it felt like the neighbourhood had changed dramatically. After over two years, the media began highlighting Yeonhui-dong as a café district. Seeing the changes, other residents gradually became more willing to renovate their homes, and now they request the project directly. It is because we have been interacting with residents for nearly 30 years and taking on various tasks. In the process, we considered the unique characteristics of Yeonhui-dong, a quiet single-family residential area adjacent to university districts, and planned a commercial space with commercial facilities appropriately distributed within a radius of 500m within a ten-minute walk.

Yoon Seunghyun: Initially, COOM Partners attracted investment due to the uncertainty of the business. Once that uncertainty disappeared, the residents, who had occupied the area for decades, turned to Kim Jongseok because of the attraction of creating additional value rather than a significant investment.

COOM Partners has renovated about 70 buildings in Yeonhui-dong.

Improvised Architecture by COOM Partners

Kim Jeoungeun: COOM Partners, led by Kim Jongseok, works fairly uniquely, in that it has been interacting with residents in Yeonhui-dong for a long time and taking on various roles. It is a kind of developer and contractor, collaborating with various architectural firms and content-based companies such as URBANPLAY. So, how did you approach the renovation of these old houses?

Lee Jinoh: Looking around Yeonhui-dong, there is a consistent feature of the buildings in which COOM Partners has been involved. For example, the way the alleyways of a walkable neighbourhood are extended into the building.

Kim Jongseok: To remove psychological barriers, gates and fences were removed as much as possible, and accessibility from the street was increased. Terraces, staircases, and bridges open up internal and external views, allowing anyone walking by to experience the space. People feel like they have their own garden, even if it’s just a potted plant in a waste space. I made the bridge because of my childhood memories of playing on a rural stream, and I got the motif for the rooftop garden from a small hill. Most importantly, I tried to capture the form of an old village within a single building. Therefore, I created alleyways within the building, and if there was a large yard, I put a building in the middle, created a backyard and front yard, and shared it with the other houses to connect them organically. The yard can be a courtyard, a sunken area, or a rooftop garden, and we have experienced that even if there is a loss of floor area, the commercial value is amplified if there is an open space in the common area.

Jeon Sangkyu: Usually, when we start a project, we work within the site’s boundaries, imagining what we want to achieve. In my case, I ended up designing several houses in the same alley, and I wish I had known that I would be doing this from the beginning because I could have given the path a different character. When did you realise you wanted to create an alley or a village?

Kim Jongseok: We knew that good visual communication creates the value of a space, but we didn’t have a clear concept of ‘alley’. By chance, I consulted with the residents of Semogil Village in Yeonnam-dong and removed all the walls. When I went back there a year or so later, there were a lot of bakeries, perfume shops, and hamburger shops. I found that the buildings inside the alley were more popular than the cafés along the roadside of Gyeongui Line Forest Park, and the rents were higher, so my idea of a landscape or village without walls expanded.

Lee Jinoh: COOM Partners uses concrete for most of its extensions and renovations. In standard extensions, steel is preferred due to the load and accuracy, but COOM Partners continues to create style and form by using the properties of concrete. Also, in some cases, exposing the concrete means that the insulation line is inside, so you have to accept some area loss in critical situations. Why do you continue to use exposed concrete?

Kim Jongseok: I did complete a steel structure once, but the new and old parts were poorly connected. There were many problems with condensation and waterproofing at the connecting parts. However, when I attached it to concrete, the adhesion was good, and it endured, even though it was waterproofed. I like the ageing properties of exposed concrete, so I often use it. I also use a lot of grey because I want the addition to the single house that has many different colours to be in harmony, so I use grey cement bricks. Also, when the tenants decorate the interior, the exterior must look good from a distance. There’s nothing like exposed concrete to make tenants stand out.

Lee Jinoh: To a certain extent, I agree that concrete is a neutral material that serves as a backdrop to everyday activities. Ultimately, it is generally believed that architecture does not exist on its own terms but exists as a background to life, and the programme was important within this understanding.

Yoon Seunghyun: I am more interested in how to organise the space and achieve a rough freedom rather than in the materials. Kim Jongseok has dealt with many things in the field, but because he hasn’t been trained as an architect within the traditional route and system, many things cross boundaries, to be honest. It can be a disadvantage or an advantage. Especially in the case of an extension or renovation, he directly expresses the desires that arise from the user’s perspective. For example, I found it interesting that the direct acceptance of the user’s desire to have something to cross the stream or flow naturally into the building along the way created an opportunity for a certain amount of valid communication between people.

190-14 Yeonhui-dong. The existing house was cleared of unfavourable spaces for expansion, freeing up the building area, and the new building was built in a space with fewer sunlight restrictions. ©Kim Yongsoon

190-14 Yeonhui-dong ©Kim Yongsoon

How Should Yeonhui-dong’s Assets Be Used in the Future?

Kim Jeoungeun: Over the past decade, many of the single houses in Yeonhui-dong have been converted into commercial buildings. Is it appropriate for Yeonhui-dong to continue to change in this way? Or what lessons can the case of Yeonhui-dong provide for other new towns or old neighbourhoods? I want to talk about the universality of the Yeonhui-dong case.

Jeon Sangkyu: It created an aesthetically acceptable result by leaving some of the existing houses in Yeonhui-dong behind and combining them through a radical splicing that resembles crossbreeding. However, it is not easy to apply the remodelling method in Yeonhui-dong to other areas. It is because the construction cost of remodelling is not often significantly reduced compared to new construction, and it is only possible if there are existing architectural assets that can embrace the trend for the ‘old’ or ‘retro’.

Hong Jooseok: It’s time to think about new uses for Yeonhui-dong. We can’t turn all the old houses into commercial facilities. The houses are ageing, and the younger generation is not moving in. However, the unique architectural assets of Yeonhui-dong have increased the value of real estate. Whether in the form of housing or office buildings, the public needs to think about a new direction.

Yoon Seunghyun: Of course, the issue of ageing needs to be addressed. Still, there are aspects of Yeonhui-dong that have changed over the past ten years that have shown people that there is a richness of life that is difficult to experience in an apartment, which has created new opportunities. So what must we do for a healthy neighbourhood in the future? So now we’re going to do another 70 projects over the next ten years? The concern is that the new towns have blocks of shops and houses. Nine out of ten are barely rented out, and the neighbourhood is not very vibrant. So it’s a question of how far you can go with the lower floors as retail and the upper floors as housing.

Lee Jinoh: If the ground floor was all commercial and the upper floors were residential, it would be a boring. However, Yeonhui-dong seems to be vibrant and sustainable in terms of a certain spatial diversity through cross-breeding even on a two-dimensional scale. I am looking forward to the interweaving of different programmes. Another valuable part of the Yeonhui-dong experiment is a kind of staggered, circular redevelopment. Although it has recently been abandoned again in terms of urban planning, Yeonhui-dong is a successful example of circular redevelopment. In particular, it is worth looking at it as an essential example of a private sector project that was created through communication with individual clients rather than a government-led regeneration. It has implications for other urban regeneration areas.

Kim Jeoungeun: Regarding the case of Yeonhui-dong, flexibility is vital for regeneration, rather than having a public masterplan and implementing it as it is but making adjustments based on the assets and reactions of the site. If the area has achieved specific self-generated achievements because it controlled the pace of change, other places should find their own pace.

Yoon Seunghyun: I agree with you both to a certain extent. Even the best planners can’t plan everything at once, and masterplans are often codified, hindering the town’s growth. On the other hand, COOM Partners didn’t plan the neighbourhood in Yeonhui-dong but instead created it through direct experience. Of course, over time, they came to think about the big picture, but because they didn’t start with a master plan and follow it, they were able to come up with some interesting things. It was also an opportunity for variation to emerge even though we had plotted a single entity. Another reason for the continuity despite the changing situation is that, to put it carefully, there was a neighbourhood architect in Yeonhui-dong called Kim Jongseok. The term Village Architect was used in Seoul Metropolitan Government about ten years ago. But it didn’t grant a proper role of a neighbourhood architect. The Yeonhui-dong case gives us a clue as to how neighbourhood architects can be best used.

Hong Jooseok: Kim Jeoungeun mentioned pace earlier, which is the most crucial aspect. Sometimes, public policy can get in the way of autonomous movement, and it’s the public’s role to create the environmental conditions for the private sector to move in a healthy way. Then, we could see many of these neighbourhoods emerge spontaneously across the country. Neighbourhoods have a wide range of resources, not just architectural assets, that can offer new forms of possibility in an era of rural decline. And speaking of neighbourhood architects, in the end, neighbourhood architects are what architects think of as MP (master planner). The real meaning of a neighbourhood architect is to expand the architect’s scope within the neighbourhood. So, it is necessary to expand the role of architects later, such as becoming a developer and then a programmer who runs a local community.

©Kim Yongsoon

PARKMENT Yeonhui is a renovation and expansion project connecting 433-6 (1970) and 433-8 (1973) Yeonhui-dong. It added 273-9 (1973) and 433-10 (1972) Yeonhui-dong, where URBANPLAY, a space management company, organises and operates a programme tailored to the ‘local yard lifestyle’. 433-8 Yeonhui-dong extended a basement and two floors to the front yard of the existing house to add neighbourhood living facilities. The structure was added to the interior of the existing house, creating a structure where the new addition intrudes into the old part. ©Kim Yongsoon