SPACE March 2025 (No. 688)

Aerial view of Immersive Resilience

Immersive Resilience seen from the south ©Kyungsub Shin

Interview Lee Changyeob professor, Hanyang University, Lee Jin co-principal, Studio ReBuild × Kim Hyerin

Kim Hyerin: The design of ‘Immersive Resilience’ is structured around complex layers of plants and architecture. Visitors wend their way through narrow passageways to experience the garden. Sensory perception differs significantly between an external view and the experience of being within the garden.

Lee Changyeob, Lee Jin: We wanted to go beyond a garden that is merely observed and instead create a space that connects nature and people, allowing for interaction. Rather than simply viewing the garden from the outside, we wanted people to experience entering nature itself as they walked or sat in the central seating area. In Immersive Resilience, visitors stroll between the winding curves and brush against the deliberately low-placed greenery as they pass. It was achieved by intentionally narrowing the passageways. We imagined that as visitors were to brush against these grasses, seeds or pollen might transfer onto their clothing, perhaps even dispersing and helping germination, symbolising the human role in nurturing life. We hoped to stir primal memories of nature within visitors by arranging perennial flowers in such a way that it would inspire this connection. Though artificial in its construction, we sought to capture a wild essence through the long blooming periods of wildflowers, the autumnal foliage, and the winter seed heads, all revealing the beauty of the seasons. The use of perennial flowers allows the emotional resonance of the four seasons to be felt throughout the year, while also allowing the flowers to grow more abundant as the day progresses. During our time in the U.K., I observed many public spaces where people shared emotional connection. I thought that such spaces were relatively scarce in Korea. So, we aimed to encourage greater visitor interaction in Immersive Resilience. Even the placement of the central table and chairs was designed to subtly blur the distinction between distance and orientation, promoting spontaneous interactions between individuals.

Kim Hyerin: Immersive Resilience is an unconventional space entirely composed of freeform curves. I’m curious about the process you underwent in conceptualising the design.

Lee Changyeob: Rather than deliberately creating a specific freeform curved shape, unique conditions and ideas emerged from the matrix of constraints and existing elements within the space. The form naturally followed this process.

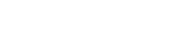

The design brief from the Seoul Metropolitan Goverment requested an approximately 270m2 space within Ttukseom Hangang Park that could offer a place of emotional restoration for its citizens. However, our goal extended beyond this—to foster a sense of connection and unity with nature, allowing people to momentarily escape the urban environment. Yet, the sensory overload experienced here and disorderly arrangement of trees, planted at irregular intervals of 6 to 8 metres, posed challenges to the design.

We sought to preserve these trees without removing or transplanting them while also finding a way to shield visitors from ground-level congestion. The existing trees helped mitigate visual clutter while simultaneously reinforcing a sense of place, allowing the project’s overall form to emerge organically from between them. Additionally, we excavated the natural terrain as deeply as permitted by drainage requirements, creating a lounge-like structure visually shielded from the surrounding environment. As this layered structure took shape, we were inspired by how bees experience the hidden space inside a flower—suggesting a means of translating that spatial sensation on a human scale.

To fully immerse visitors in nature, the planting was arranged in three distinct layers, increasing in height toward the outer edges. This approach enclosed the space in a 360-degree embrace of greenery, enhancing the experience of retreat and deepening the connection with the natural world.

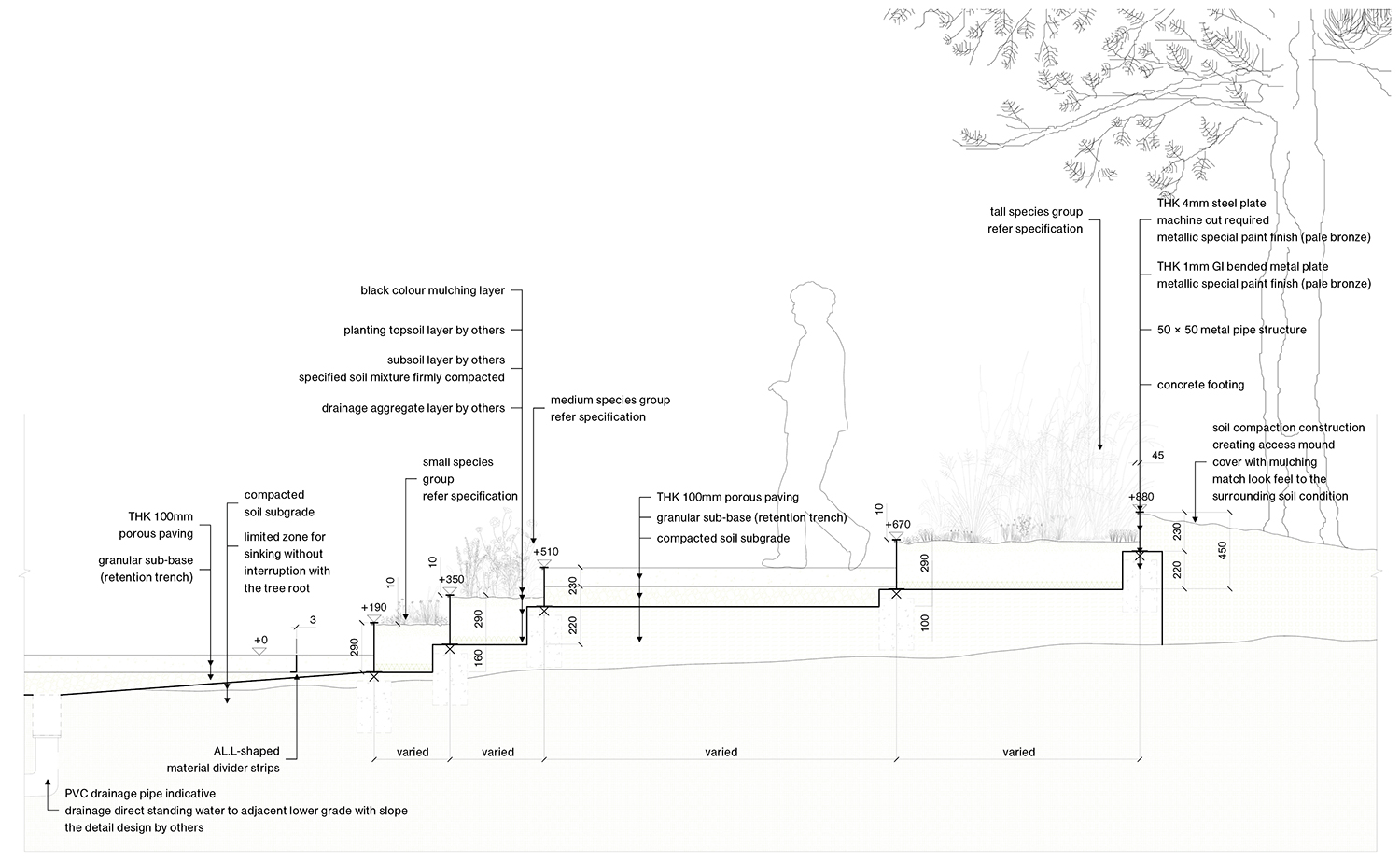

Pre-assembly of the structure

On-site assembly of the structure

©Kyungsub Shin

Kim Hyerin: Computational design played a significant role in implementing the complex structure and enhancing construction feasibility. Can you elaborate on this process?

Lee Changyeob: Computational design is not just a tool for shaping certain forms, it is an essential technology can be employed throughout the entire design process; from ignition to construction, within the constraints of time, budget, and resources. It enhances the efficiency of traditional architectural production processes while enabling a greater variety of ideas to be realised within budgets comparable to standardised designs. The Immersive Resilience project actively leveraged computational design to maximise efficiency and elevate fabrication quality within the constraints of a public design budget. Once the initial concept was established, a parametric twin model was pre-constructed within the computer to create an environment where core parameters – such as curvature and the minimum width of planting beds – could be verified. Most of the fabrication process took place in a factory, where approximately 400m of layered structures were systematically classified into ‘parts’, ‘units’, and ‘mega frames’ to ensure smooth execution. The curved forms were optimised with varied segments for linear cutting to minimise material waste, and around 700 bespoke parts were assigned unique labels and groups for efficient management. Additionally, these parts were pre-assembled into transportable units, reducing the need for on-site labour. During construction, the complex structure was designed to be assembled as seamlessly as an IKEA flat-pack. The five rings were assembled one by one, starting from the innermost ring at a pace of one per day. As the rings extended outward, the number of parts required for assembly increased. However, as workers gained experience, they were able to complete construction within the planned schedule.

Kim Hyerin: Although its structure is made of metal, its materiality doesn’t feel overtly prominent. What considerations did you have regarding the materials?

Lee Changyeob: While I generally prefer materials that age naturally over time, the constraints of a public project – particularly budget limitations – necessitated a different approach. I was also mindful of potential maintenance challenges, making it essential to choose materials where dust accumulation would be less noticeable. To address this, we collaborated with the Syatt team to apply an artisan metallic finish to the steel structure, while the tables and chairs were crafted from aluminum, treated with a combination of tinting and hand-finishing techniques. Rather than creating a stark contrast with the surrounding greenery, our goal was to achieve a subtle resonance, allowing the materials to interact harmoniously with the landscape.

©Kyungsub Shin

Kim Hyerin: Considering sustainability, the plant selection must have been a particularly important aspect when crafting this naturalistic garden.

Lee Jin: We aimed to create an experimental garden entirely composed of perennial flowers rather than the more commonly seen trees and shrubs found in many of Korea’s parks and gardens. There were concerns about the lack of vertical elements, which could reduce the sense of three-dimensionality, and about the winter garden landscape when plants enter dormancy. However, I believe that more design experimentation with perennial flowers is required. We exclusively used perennials because, in typical public spaces, annuals are planted in the spring or autumn, and once their blooms fade, they are discarded. The water, energy, fertiliser, and the countless plastic pots used for these plants all gets wasted. Even when using annuals, we should be mindful of not simply planting and discarding, but instead of thinking about natural disperse, and carefully allowing them to grow with other perennials. However, this approach requires significantly more workforce and maintenance costs. In contrast, perennials, by nature, thrive without artificial irrigation, growing like wildflowers. Of course, it demands more attention than a garden made up only of shrubs and grass, so not many people attempt this approach. I believe, however, that conducting such experiments in public gardens is meaningful.

Kim Hyerin: What is the proportion of indigenous species in your planting design?

Lee Jin: In Immersive Resilience, the use of native species was not as extensive as I had hoped. One challenge is the lack of publicly available research or well-organised data on native species for garden use in Korea. For plants to thrive in a garden, they must coexist with non-native species and withstand the competition. In public gardens, particularly for perennial flowers, we can only use varieties available in nurseries, and the range of options is quite limited at present.

©Kyungsub Shin

Kim Hyerin: In Korea, the term ‘gardener’ is somewhat unfamiliar. Do you personally distinguish between a landscape architect and a gardener?

Lee Jin: Personally, I prefer to be called a ‘gardener’ or ‘garden designer’ rather than a ‘landscape architect’. This is because I want the spaces I create to be as close to their users as possible, and I place just as much emphasis on nurturing and maintaining gardens as I do on designing them. I aim to achieve this by incorporating a diverse range of herbaceous plants—an aspect often overlooked in Korea’s landscape architecture field. In practice, the boundaries between these roles are not always clear, and these distinctions are not necessarily significant.

Kim Hyerin: How were discussions between the architect and the gardener carried out?

Lee Changyeob: As a married couple, sharing opinions came naturally, and we developed the design together from the outset. From a garden designer’s perspective, Jin focused on practical aspects essential to plant sustainability, such as the size of planting areas, ensuring plants could breathe within the soil, and considering how human circulation should be integrated into the space. Meanwhile, as an architect, I worked on translating ideas into three-dimensional space, addressing structural constraints, materials, and drainage while synthesising various challenges. Rather than strictly dividing our roles, however, we sought to integrate our expertise, aiming to redefine the relationship between architecture and landscape in a new way. At the core of our collaboration was a shared goal: to enhance the qualitative experience of public spaces in Korea through captivating placemaking.

©Kyungsub Shin

Kim Hyerin: How do you envisage the future development of Immersive Resilience and the collaboration between Lee Changyeop and Studio ReBuild?

Lee Jin: The core of my work as a garden designer lies in public contribution. I majored in public policy at both undergraduate and master’s levels, and my first job involved creating public policies. Creating quality public spaces simplifies the complex processes of policy implementation and is one of the most direct ways to engage with citizens. For this reason, I want to create more spaces in Korea that can convey a ‘sense of community’. Unlike buildings with physical walls, gardens have only soft boundaries, and I think people can experience a much more diverse and free range of sensations within them. Through this psychological expansion and respect for the plants and animals within the garden, I want to create spaces where people can move away from anthropocentric thinking and contemplate the issues from an ecological perspective.

Lee Changyeob: When we established the studio, we sought to blur the rigid boundaries between architecture, landscape, and spatial design, challenging the conventional subdivision of these disciplines. Rather than creating a building that merely exists within a predefined social system, we aimed to design a place that embodies something entirely new – something unfamiliar – where meaningful connections between diverse entities could emerge. I see immense potential for expanding the structural framework and systems developed through the Immersive Resilience project. For instance, what is now conceived as a pathway could evolve into a spatial mass that integrates more diverse activities rather than serving solely as a circulation route. Of course, the current design responds to the unique spatial context of Ttukseom Hangang Park, and naturally, its form and spatial experience would adapt to different sites. However, on a broader scale, I envisage this concept evolving into a multidimensional ecological system—one where a greater diversity of people, both human and non-human life forms, can gather, interact, and become deeply interconnected.

Moving forward, I believe architecture must be approached with a more ecological and holistic mindset. When buildings become an active part of an ecological system rather than isolated objects, people develop a stronger sense of belonging and attachment to them, ultimately extending the building’s lifespan. In the face of the climate crisis and pressing environmental challenges, these shifts in architectural thinking must take root. While such projects remain rare in Korea and are not yet widely visible, we are committed to demonstrating the value of this approach – one that is true to the spirit of our studio’s name, ‘ReBuild’ – by building in ways that depart from convention and embody the principles to which we hold fast.

Typical section detail

Overall process diagram from design to fabrication