SPACE April 2025 (No. 689)

View of Maison & Objet

Woojai Lee, Bleu, newspaper & mixed media, 350 × 350 × 500mm each, 2025 ©Woojai Lee

The design fair Maison & Objet was held last January from the 16th to 20th, in Paris, France. Every year, the fair’s ‘Rising Talent Awards’ unveils the up-and-coming talent of a selected country. Noteworthy young artists and designers under 35 years old are invited to showcase their work to a jury of French and guest experts. This year, Korea took centre stage at Maison & Objet. At a time when Korean artists have already been thriving internationally, sharing and communicating their work, SPACE take a look at what was on display in order to gain an insight into French perspectives on Korean design.

Front chair work. Minjae Kim, Chaise de Douleur, douglas fir, lacquer, stain, acrylic paint , 87.5 × 45.5 × 35.5cm, 2025 ©Minjae Kim

Korea, This Year’s Rising Talent

Maison & Objet is one of Europe’s largest B2B design fairs, founded in 1949 by the Atelier d’Arts de France and RX, and continuing to this day under its present name. The biannual five-day event is participated by over 70,000 design professionals, with 2,500 brands from upto 150 countries. Unlike Art Basel or Milano Design Week, which are firmly embedded in their city centres, Maison & Objet can only be reached by traveling around 20km to the north-west of Paris on the weathered regional express train. A certain French flair manifests at the Paris Nord Villepinte Expo Center. People wander through the 200,000m2 expanse, taking in its packed exhibition booths, with a certain spring in their step. Not so much a lavish extravaganza, the fair is a place to flâner—to meander through its spaces while rummaging and reflecting, until, at last, one seizes upon the extraordinary. This year, seven Korean ‘rising talents’ were unveiled. Today, Korean culture is receiving international recognition like never before. What are the creations and concerns that motivate theses young Korean artists, as they make their global mark?

Kim Minjae (produced by Garcé Dimofski), Mínio Sconce, brushed aluminum and mahoganny wood, 56 × 16 × 32cm, 2024

Revisiting Present Identity

This year’s awardees were all born after 1989, the year which saw the lifting of overseas travel restrictions in Korea. The awardees have been shaped by extensive education and work opportunities abroad, yet exhibit a desire to explore issues of belonging and cultural identity. According to the artist Kim Minjae, it’s ‘a generation that was born in an entirely westernised Korea, and hence faced a sort of identity crisis’, adding that ‘having grown up in oblivion of what it means to be Korean, has a renewed thirst to explore this as adults’. If Korean design was prone to importing or mimicking Western trends just thirty years ago, today it is ‘strongly asserting its Korean identity, as if to recover its spirit and character. While reconciling with its fundamental roots on the one hand, it is torpedoing into modernity’. (Vincent Grégoire, jury of Rising Talent Awards)

KUO DUO, VINO CHAIR, client: WEKINO, beech wood, color finishing, 392 × 446 × 783mm, 2024 ©KUO DUO

The Bleu (2025) series by the artist Woojai Lee is composed of serene handcrafted rectangular and cylindrical sculptures in luminescent blues and greys. The artist collects newspapers, which are then swollen and dyed into a pulp, and then moulded into the desired form or shaped with wooden frames. The title Bleu alludes to how one of the most loved colours today was historically culturally undefined in Europe. This historical anecdote serves to portray the artist’s aspirations for the overlooked, exemplified through newspapers or his identity. Lee’s formative background includes spending three decades split across Korea and New Zealand and Europe, giving way to earlier works that persistently questioned his sense of belonging as a Korean. For example, his medium of choice – easily cast aside newspapers rather than traditional hanji – was used to assert his sense of self, while steering clear of being framed as what is thought of as typically Asian in the West. As his works gain recognition at home and abroad for their calm, refined and intrinsically Korean look, thematic boundaries are expanding to include modern Korean cityscapes—the wooden beams of the hanok, the shadows cast by high-rise apartments, and interposing aspects of nature.

KUO DUO, REEL HANGER, client: WEKINO, die-cast aluminum, 400 × 91 × 230mm, 2023 ©KUO DUO

Minjae Kim’s photograph Chairs (2023), depicting the artist’s prolific output as a furniture designer since his post-pandemic rise to fame in New York, serves as a backdrop to the poignantly placed Chaise de Douleur (2025)—a carved wooden chair with a defiantly raised fist. The set up frankly states the artist’s misgivings about his chosen path given the state of world affairs today. His chairs and furniture pieces, decked with their own quirky personalities, carved and lacquered by hand evade both ‘text-book tradition’ and the ‘East seen by the West’, drawing instead on childhood revelations such as his school route in old town Seoul. Helmet Lamp (2022) seems to be topped with a Chosun dynasty hat, Bat Chair (2023) is framed with dragon like wings, La Chaparrita (2018) teeters on a mini-stage; mixed with authenticity and tradition, his works elicit a strong sense of nostalgia within the confines of contemporary expressionism and avant-garde.

NICEWORKSHOP (Oh Hyunseog, Yoo Sangmyeong), ALUMINUM SCRAP SERIES, material partnership with FORMAT, aluminium scrap, resin, various dimensions, 2025 ©Kim Jinseob / Image courtesy of NICEWORKSHOP

NICEWORKSHOP (Oh Hyunseog, Yoo Sangmyeong), ALUMINUM FORMWORK SERIES, material partnership with FORMAT, aged and new aluminium form, bolts, nuts, various dimensions, 2024 ©Kim Jinseob / Image courtesy of NICEWORKSHOP

Offshoots of the Hybrid City

Korean design is also seen from abroad as speedy and dynamic. Market trends are read fast, production drive is high. Opportunities to collaborate open up everyday and are instantly taken up. Some note that ‘this creative energy, unique to Korean design, originates from; the industrial strength and technological prowess of Korea, as well as a backdrop of its soft power with a global impact’. (Franck Millot, director of Rising Talent Awards.) Yet, this dynamism is not solely due to economic growth, but also the result of ‘a singular and dynamic urban environment conducive to production, where hybridity is established from the clashing of different cultures and times—from Joseon dynasty palaces and crude manufacturing sites from post-war industrialisation, to futuristic skyscrapers emblematic of rapid economic success’ (Youngshin Jang, jury of Rising Talent Awards). Artist residencies in the Bukchon hanoks, Gwanghwamun’s skyscrapers just a stone’s throw away, Euljiro’s retro bars reminiscent of the 1970s and 1980s, are all facets of Korean cities and consumable spaces that inject a sense of dynamism into its design scene.

The design duo, KUO DUO (co-principals, Hwachan Lee, Yoomin Maeng) explores untread ground with their unique design language, as seen in VINO Chair (2024) and REEL HANGER (2023). Drawing from their experience of working at design studios abroad, they experiment with new methods, on an undefined set of materials. What comes across a set of curves in motion made up of pliable ceramics, is in fact iron cast aluminium, with a casted finish. The vibrant beechwood tables and chairs of Vino Collection employ 3-axis CNC machining to create comfortable seating with smooth tactile surfaces. This experimental approach towards material, form and technique become optimised through new attempts with the materials, forms, and techniques of the two designers, optimised through the city’s creative ecosystem, where firms of all scales exist in dense cohabitation. Euljiro’s tiny hardware parts stores allow for experimental and speedy prototyping using different industrial materials, like wood, metal, paper and rubber. The duo also collaborate with specialists when in need of further expert opinion.

The design studio NICEWORKSHOP (co-principals, Hyunseog Oh, Sangmyeong You) repurposes industrial materials from the rapidly changing face of the Korean city. The tables and benches of ALUMINUM FORMWORK SERIES (2024) result from minimal manufacturing – just nuts and bolts – used to assemble aluminium formwork used for concrete moulding on construction sites. Part of the series, Aged form Line (2024), reveal the textural traces of a repeated shot blasting treatment to remove the concrete debris. Graduates of interior architecture, the two designers found themselves managing renovation projects with fast turnaround to meet market demand. Acknowledging the extent of building materials and waste generated in these projects, the artists started designing and producing their own furniture, using these reclaimed materials. To this end, they have also collaborated with the upcycling firm FORMAT, which produces, repairs, and rents aluminium formwork to construction sites across the country. In Europe—where lower buildings and timber formwork remains the norm, their choice of material has elicited interest as unexpected and out of the box.

Artist Lee Sisan’s Proportions of Stone (2019 – present) series portrays how balance and harmony can occur by contrasting radically artificial urban environments with nature in its purest form. Weathered stones are hand-picked by the artist to act as centrepieces in his designs. As a consequence, imitation cast stones, steel, aluminium or glass panels are added to complement form and function. This process entails replacing the standardised dimensions with those of nature. The stools and chairs of the Neo-Primitive (2022 – present) series, depicting what one could easily imagine appearing on a forest trail, are collected twigs and branches that have been brought to life as cool aluminium reproductions, gilded with a primitive yet futuristic touch. Lee explains that working in commercial interior design – in short, whatever project comes his way – has actually enriched the artist’s experience of discovering, exploring, and imagining unfamiliar materials, finishings, woodwork or metal crafting techniques. As a departure from his earlier work rethinking artificial and natural dimensions, his more recent works posture towards the exposure of underlying systems found in industrial processes.

In Yeonghye, Frida, velvet, cotton, hand-sewing, 20 × 50 × 40cm, 2024 인영혜, ‘프리다’, 벨벳, 솜, 손바느질, 20×50×40cm, 2024

In Yeonghye, Reflection 6, velvet, cotton, hand-sewing, 67 × 20cm, 2024 ©Roh Kyung / Image courtesy of In Younghye

A Handcrafted Discipline

France was the first country in the world to establish legal frameworks for the arts and crafts, with 281 clauses finely defining the profession—from the treatment of materials, to specific techniques and the mark of the atelier. Put differently, the professional scope of the designer, artisans and artists is clearly defined. In contrast, from a French perspective, Korean design has more ambiguous distinctions between its professions. To quote, it is ‘marked by a strong and vibrant tradition of craftsmanship and artisanal knowledge, as well as by a practice at the intersection of art and design’. (Franck Millot) What is the source of this practice-based approach? The jury member Youngshin Jang explained that Korean aesthetics values process over output—‘in particular, that of practicing and realising one’s work through an internal dialogue with the external world. One could say that the artist’s journey to self-realisation is initiated with the artist’s meditative movements to prepare their ink, rather than the moment the brush hits the canvas.

In Younghye proposes a space of comfort and respite, inviting visitors to touch and engage with her sculptures made of hand-stitched, bulging pockets. The embroidered drawing Walk on Eggshells (2021) features a sheepish and wary character with a heavily arched brow, borne from the draining experience of interacting with others in the outside world. The piece was completed by countlessly retracing the lines with her sewing machine, similar to the act of pressing down hard while journaling. Distortion (2024) and Reflection (2024) are also incarnations of warm childhood memories, like her mother making her clothes, stitching socks with her sewing kit, or playing in the enamelled sinks of her parent’s furniture store. They are manifestations of the artist’s desire to become an ‘object of sacrifice’ for those in need, a sentiment felt after being cast out ‘defenceless’ into the professional world after leaving school.

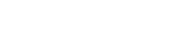

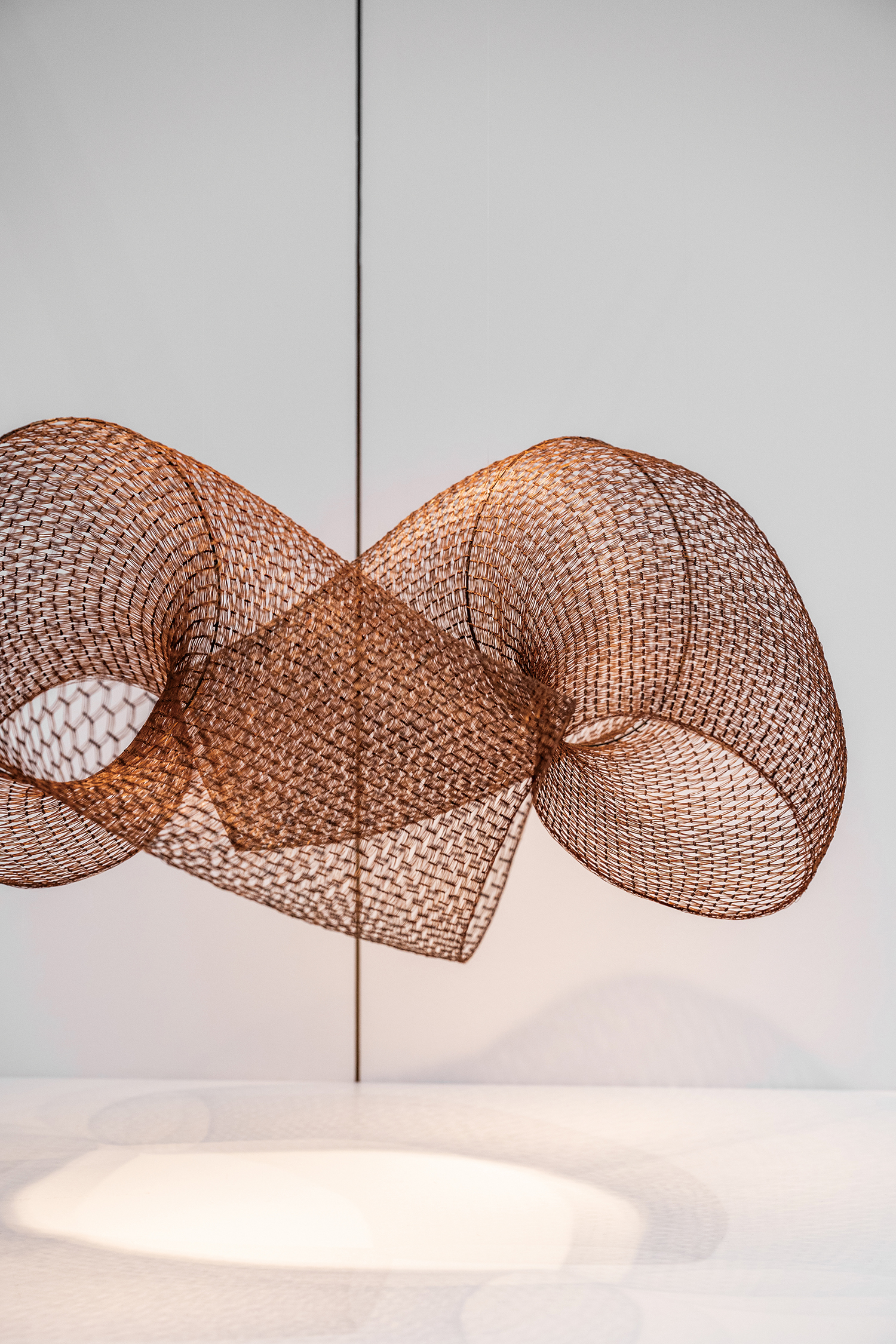

Dahye Jeong’s horsehair craftwork shines with a minimal and understated charm, featuring lightly woven luminescent three dimensional objects. In the Joseon era, horsehair crafted headpieces like manggun, tanggun or gat, symbolised Confucianism traditions of self-discipline over one’s mind and body, with elites using them alternately throughout the course of a day. At the time, horsehair patterns proliferated nationwide, then started to lose their diversity in the late Joseon era, dwindling away to finally be largely lost today. Jeong’s work also involves reviving these patterns, and even developing her own geometric, more modern inventions. Crescent Moon (2023), Three Flowers (2024) and Diamond (2024) are all examples of such intricate and exquisite work. The Jeju-based artist – once the hub for horsehair production – resolutely wishes for each of her days to be lived fully, with dedication, like the painstaking stitching involved in her process.

Lee Sisan, Proportions of Stone_Shelf 01, stainless steel, natural stone, 110 × 35 × 150cm, 2021 ©Lee Sisan

Lee Sisan, Proportions of Stone_Wall Object 08, stainless steel, natural stone, 60 × 26 × 60cm, 2024

Lee Sisan, Proportions of stone_series, stainless steel, natural stone, various dimensions, 2019 – 2021 ©Lee Sisan

For Rising Talent, Everyday is a Feast

This past year has seen Korean fine arts surge past mainstream trends like K-food, K-drama and K-pop, making headlines like Han Kang receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature and Cho Minsuk’s design of the Serpentine Pavilion. Regardless of the Korean wave, this year’s Rising Talents as have already established themselves abroad, carving out their individual paths through a vast array of brand partnerships, design events, awards, and their social media presence. Gone are the days of the 1990s, and 2000s, when importing foreign designs was deemed more important than sending Korean design abroad, or when an artist who won a prize abroad made the nine o’clock news back home. While Korean design today still can’t quite be pinned down on a map, it is rapidly building its reputation as a genre that is both intricate yet daringly experimental, trend-sensitive yet with its own pronounced aesthetic. When asked ‘why Korea, this year?’ the organisers responded ‘rather, why did it take so long?’ An artist said that ‘it has never been as easy as it is today to work abroad as a Korean artist.’ Harnessing the interwoven roles of artist, designer and artisan, Korean design is pressing on, zigzagging between the realms of authentic human touch and natural materials, and offering surreal visions of futuristic cityscapes. Perhaps, one could say that designers are living in the moment in celebration of this veritable feast.

* In reference to Hemingway’s Paris is a Moveable Feast (1964)

Dahye Jeong, Smoothly Rounded, brown horsehair, 55 × 66 × 17cm, 2024

Dahye Jeong A Time of Sincerity, black horsehair, 31.5 × 29 × 24cm, 2025

Dahye Jeong Three Blossoms, black horsehair, 24 × 24 × 22.5cm, 2024