SPACE May 2025 (No. 690)

SPACE is preparing an archival book, Archiving International Architecture Exhibition at the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 1996 – 2025 (tentative title), as part of the ‘30th Anniversary Archival Research of the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale’, organised by the Arts Council Korea (ARKO). The archive book, scheduled to be published in May 2025, will include interviews with the commissioners of the early exhibitions at the Korean Pavilion, and will be published in a series of SPACE. Through these interviews, SPACE will reconstruct a narrative of the early years of Korean architecture exhibition history centred on the Venice Biennale and reflect on the meaning of the Korean Pavilion as it celebrates its 30th anniversary.

The Venice Biennale and the Korean Pavilion: Past, Present, and Future

The series of interviews with four early commissioners of the Korean Pavilion, Kang Sukwon, Kimm Jong Soung, Joh Sungyong, and Seung H-Sang, presented vivid and first-hand accounts of how the exhibitions in the Pavilion were organised and introduced to global audiences at the Venice Biennale. SPACE met with Pai Hyungmin (professor, University of Seoul) for the final interview in the series of interviews conducted on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the Korean Pavilion. Since participating in the Venice Biennale in 2008 – the year Seung H-Sang was the commissioner – as a documentor for the Korean Pavilion, he has been directly and indirectly involved with the Venice Biennale in a variety of roles. Working as an architectural historian and critic in 2008, Pai Hyungmin established himself as an ‘architectural curator’ with participation in the main exhibition in 2012 and as curator of the exhibition in the Korean Pavilion in 2014, the year it was awarded the Golden Lion. In this interview, he examines the meaning and role of the Venice Biennale as a stage upon which to exhibit architecture, based on his critical perspective as a historian and his specific experience as an insider, while also pointing out the implications of changes made to the architecture exhibitions in the Korean Pavilion over the past 30 years. He also discussed the desired and demanded future image of the Venice Biennale and the Korean Pavilion in the context of the rapidly changing state of international affairs.

2008 베니스비엔날레 당시 베니스 현지에서 배포된 한국관의 리플릿 앞장 펼침면 Front spread of the leaflet of the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2008, distributed in Venice

The Korean Pavilion in 2008, ‘Critical Topic: Pajubookcity as Culturescape’

Bang Yukyung: I believe your first participation in the Venice Biennale was in 2008, when Seung H-Sang was commissioner of the Korean Pavilion. Prior to that, what was your perception of the International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale (hereinafter Architecture Exhibition)?

Pai Hyungmin: It was in 2008 that I first participated in the Venice Biennale. At the time, I think the Venice Biennale was still perceived in Korea as a kind of wind vane of world architecture. We were at the periphery, not the centre of the architectural world. The Venice Biennale was perceived predominantly as a Western-centric stage where famous architects gathered to show their work, competing almost as if it were the Olympics. It was Chung Guyon’s ‘City of the Bang’ (2004) that first made me aware of the Venice Biennale. It was an exhibition that showed us how we would present ourselves on the largest global stage. Before 2004, it was difficult to imagine an exhibition that went beyond architects simply showing their work. Showing Korea’s everyday urban condition through architecture was quite novel at the time. In this respect, the approach to Paju Bookcity in 2008 was also meaningful in that it moved away from exhibiting buildings. My experience in Venice in 2008 was an important foundation for my growth as a curator.

Bang Yukyung: How did you feel when Seung H-Sang asked you to participate in the Korean Pavilion as a documentor? I would also like to hear about your collaboration with Choi Moongyu, the curator at the time.

Pai Hyungmin: ‘Documentor’ is actually a title that officially doesn’t exist in the organisation of the Biennale. In reality, my role was a curator. It was my first project as a curator, but because I was called a documentor, my role has become confusing. Personally, this is a bit disappointing for me. Choi Moongyu was in charge of the design of the exhibition, and I worked on the content, so the composition was clear. At that time, Ga.A Architects, Choi Moongyu’s office, was only 100m from where I lived. I worked a lot at Ga.A Architects for the exhibition. The vibe was good and we worked very well together.

Bang Yukyung: Including Seung H-Sang’s solo exhibition, there have been a number of exhibitions in Korea and abroad on Paju Bookcity and its architecture. But I believe it was at the Venice Biennale that the video documentation of the process of creating the city was shown for the first time.

Pai Hyungmin: In 2005, there was an exhibition about Paju Bookcity at the Aedes Gallery in Berlin.▼1 I wasn’t involved at that time, but the previous exhibitions related to Paju Bookcity was mostly concerned with its buildings. The scope of the Korean Pavilion, on the other hand, was much broader as it dealt with its history and the people who created Paju Bookcity. I wanted to bring together a wide range of stories from the people involved, and we couldn’t do that without video. Because the history of the publishing industry creating an industrial complex goes back to the 1980s. I interviewed everyone from publishers (including the publishing companies’ principals), editors, designers, architects, and residents of nearby neighbourhoods and the Paju Bookcity. Looking back at 2008, I was much younger then, enthusiastically talking with everybody. (laugh) The interview process was a very meaningful experience for me.

Bang Yukyung: I was also curious about how you and Choi Moongyu discussed the medium and organisation of the exhibition.

Pai Hyungmin: It was Choi Moongyu’s idea to have an exhibition centred on video. Following the spatial nature of the Korean Pavilion, we divided the exhibition into three sections: ‘THE PLACE’, ‘THE BOOKS’, and ‘THE VOICES’. Together, we came up with the structure. I collected visual material related on Paju Bookcity to show the history of its formation and development through video. We decided to install a series of multi-screen videos presenting the sounds related to it in chronological order. In our own way, we wanted to present a spectacular exhibition. In ‘THE PLACE’ section, a U-shaped space, we placed aerial photographs of Paju Bookcity on the floor and installed a continuous series of screens, like a horizon, as a synchronised multi-channel installation. At the time, multimedia installation was rare and technically very difficult to realise. We installed a computer for each screen behind the temporary display wall and we had to go in and out to constantly adjust and fix them. The media programmes are easier to handle now but at the time they would stutter and stop and the video timing would be off. (laugh) Next to the ‘THE PLACE’ was ‘THE BOOKS’ section. We prepared the installation by hanging the books published by Paju Bookcity. When you enter the Korean Pavilion there is a long room and a round area. So we set the ‘THE BOOKS’ section in the round space, and in ‘THE VOICES’ section was placed in the brick room. ‘THE VOICES’ section was divided into three parts as a synchronised multi-screen installation.

Bang Yukyung: That was a groundbreaking attempt at the time. Who was in charge of the actual video work?

Pai Hyungmin: The people in charge of filming and editing are now known as Giraffe Pictures. I believe this was Kim Jongshin and Jung Dawoon’s first project when they returned to Korea after studying in the U.K.▼2

Bang Yukyung: So that was how they were able to produce a film like the Great Contract: Paju, Book, City (2022).

Pai Hyungmin: You’re right. I believe their work for the Korean Pavilion served as a foundation.

Bang Yukyung: I heard from Seung H-Sang that the dinner reception was really great.

Pai Hyungmin: It was held in the garden of Carlo Scarpa’s Querini Stampalia Foundation. The dinner reception was impressive and the space was beautiful. The exhibition opening ceremony was held in front of the Korean Pavilion. Among the photos of the exhibition opening, there is one where I am interpreting for Arts Council Korea (ARKO)’s chairperson, Kim Jung-heon. (refer to p. 114) That’s Choi Moongyu, me, Seung H-Sang, and Kim Jung-heon. The chairperson is the younger brother of Kim Jungsik, the founder of the Mokchon Foundation. The three brothers of that family are well known. The eldest, Kim Jung Chul, and the younger, Kim Jungsik, together founded Junglim Architecture, and the youngest Kim Jung-heon was a painter and an important figure in the art world.

Bang Yukyung: I heard that only posters and leaflets were distributed at the exhibition. Who was in charge of the graphic design?

Pai Hyungmin: It would have been Hong Dongwon. Bang Yukyung: Was there a particular reason why there was no separate catalogue produced for the exhibition? Pai Hyungmin: There may have been several reasons. A book on Paju Bookcity▼3 was planned to be published by Kimoondang Publishing. Because of that book, we didn’t think of making a catalogue. There wouldn’t have been much difference between the Korean Pavilion catalogue and the book. Furthermore, we didn’t have enough budget for the exhibition at that time.

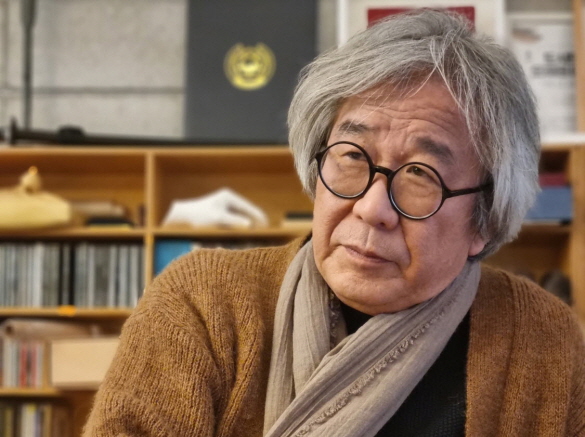

Exterior view of the Korean Pavilion, which was shown in ‘Common Pavilions’, the part of main exhibition of the Venice Biennale 2012. This photo, taken by photographer Gabriele Basilico, was also featured in the catalogue of the Korean Pavilion at the 2014 Venice Biennale. Source: Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula, Archilife, 2014, pp. 10 – 11.

Main exhibition in 2012, ‘Common Pavilions’

Bang Yukyung: Have you participated in the Venice Biennale since 2008?

Pai Hyungmin: I was invited to be part of the main exhibition when David Chipperfield was the director under the theme ‘Common Ground’. The exhibition was called ‘Common Pavilions’. The national pavilions in Giardini were interpreted and explained by someone from each country. Along with the black and white photographs of the national pavilions, I was involved in producing an interpretive text and its audio narration of the Korean Pavilion in English and Korean. Gabriele Basilico, who took the photographs, and the curator Diener & Diener Architects were also modernists like David Chipperfield. So the exhibition space and the installations were very neat and clean. I did a lot of intensive writing and was able to expand my interest and interpretation of the Korean Pavilion. The exhibition catalogue was also nicely published in a large format. The text I wrote at that time was later republished in the catalogue of the Korean Pavilion’s Art Exhibition the following year. As you know, Kimsooja’s work itself was an interpretation of the Korean Pavilion.▼4

Bang Yukyung: For ‘Common Pavilions’, how did you interpret the Korean Pavilion?

Pai Hyungmin: The look of the early national pavilions in Giardini, built as exhibition galleries during the imperial era, is a bit strange. In particular, the pavilions built at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century were designed in a classical, authoritarian style. The buildings are small in scale but designed like large buildings. So those kinds of exhibition pavilions felt like mausoleums. In the way that rich Western millionaires built their private cemeteries, they were designed with pediments and orders, in the classical style. In contrast, the Korean Pavilion felt like a private house. The following is the way I described the Korean Pavilion.

Giardini is a kind of city. During the Biennale, it is a bustling garden city of small museums. Otherwise, during long periods of inactivity, it feels like a luscious necropolis of large mausoleums. In this strange city, there is a pavilion that eludes both of these designations. The Korean Pavilion is more like a house. Secluded behind the Russian, Japanese and German pavilions, undetected along the subaxis of Giardini, it has the scale and privacy of a house. From the exterior, the different elements – a pre-existing brick shed, a tiered cylinder, a light steel-framed entrance – seem to designate the different functions of a house. It has a front garden, a back yard, and a roof terrace. We enter through a porch, into a spacious rectangular hall. It is a bright “living room” with a sky-light and ample glass walls that filter light through wooden screens. Fold up the wooden screens and hang them on to cantilevered canopies, as you would in a hanok (the traditional Korean house), and the living room opens up to the gardens and the waters of San Marco Canal. There are even back porches that look out to the Canal. [...] Though the Korean architect Kim Seok Chul is better known for his aggressive, sculptural forms, in his engagement with the Korean house, he has produced an accommodating space. It is a space that allows itself to be adapted and changed, all within the scale of the house. It is a kind of hospitality that distinguishes it from most of the heavy monuments in the Giardini. We may contrast it, for example, with the German Pavilion next door, whose history and forms have provoked strong responses. We will certainly not forget Hans Haacke’s entry as a self-made vandal, smashing the marble floors furbished under the direction of Hitler. In the short life of the Korean Pavilion, its exhibitions have reacted to the building and transformed it in different ways. Because of the sheer scale and locality of the pavilion, the Korean exhibitions have absorbed and performed this peculiar domestic scene.

_Excerpted from Pai Hyungmin, ‘Dwelling on the Korean Pavilion’, Common Pavilions, Scheidegger & Spiess, 2012, pp. 263 – 265.

In other words, if a national pavilion of the West is a maoseleum, the Korean Pavilion is a house. For many reasons, the Korean Pavilion is open to the outside. By appropriating a brick building that was originally used as a toilet, it became the only national pavilion with a toilet. I see that feature as something positive. In the art world, there have been a lot of negative evaluations of the Korean Pavilion as an exhibition space. I think the attitude of a contemporary artist should be to recognise the building as a given condition, accept it in a positive way rather than forcibly turning it into a white cube, like the way Kimsooja did in the Venice Biennale 2013.

Bang Yukyung: You seem to have experienced the Korean Pavilion in diverse ways through many different opportunities and events.

Pai Hyungmin: In 2012, I visited Venice several times for the ‘Common Pavilions’. During the opening, I saw the exhibition in the Korean Pavilion. At that time, there was a lot of controversy about the selection of the commissioner and the participants, as well as the quality of the exhibition. So from 2014, the commissioner was selected through a public competition. From 2008 to 2023, I have seen all the exhibitions in the Korean Pavilion, except for 2021, which I was unable to see due to the pandemic. For this period, I will be able to talk about the Venice Biennale in general, while specifically pointing out the exhibitions I was directly involved in.

Exterior view of the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2014

The Korean Pavilion in 2014, ‘Crow’s Eye View: The Korean Peninsula’

Bang Yukyung: In 2014, you again worked as the curator of the Korean Pavilion. I would like to know how the thematic competition, adopted for the first time for the Korean Pavilion, went that year.

Pai Hyungmin: I was deeply involved in the application process for commissioner in 2014. I was part of both Kim Young Joon’s team and Cho Minsuk’s team, both final candidates. I participated in the thematic planning of both teams. Seung H-Sang was the chair of the selection jury, and as I recall, Kim Young Joon did not show up at the final presentation. Instead, Yeum Sanghoon (currently professor, Yonsei University), who was a member of the team, gave the presentation. Naturally, the jury leaned in favour of Cho Minsuk. Of course, Cho Minsuk’s theme was extremely attractive. I heard that in the jury discussion, there was some controversy about the feasibility of dealing with North Korean architecture. Others also questioned whether it was an appropriate theme for the Korean Pavilion. Rem Koolhaas, the director, presented ‘Fundamentals’ as the general theme, but for the national pavilions presented the theme of ‘Absorbing Modernity’. Rem saw the outbreak of World War I in 1914 as the beginning of modernity and 100 years later presented a historical theme. It was the first time that the director had set a separate theme for the national pavilions. Because of the influence of Rem Koolhaas, all the national pavilions responded in a serious manner. It was a very unique situation in 2014. Rem was orchestrating the entire exhibition, but because he was so aware of the national pavilions, the selection of the Korean Pavilion commissioner had to be strategic. The architects who worked under Rem are spread out all over the world, and it just so happened that both Kim Young Joon and Cho Minsuk had worked at OMA. Looking logically at the theme, Cho Minsuk’s team had the more convincing proposal as the division of North and South Korea is undeniably the fundamental modern condition of the Korean peninsula. After winning the Golden Lion award, I made a relative evaluation of the other national pavilions. My sense was that they were too retrospective. In dealing with a historical theme, they lacked a sense of the present. They were certainly interesting, but they felt like stories from the past. In contrast, North and South Korean architecture made us think about a very uncertain future. Because we don’t know how the relationship between North and South Korea will evolve, the exhibition was full of tension between the present and the future. Hence, it felt less like a story of the past and more like something emerging in a new way. The effect of the exhibition was quite special.

Bang Yukyung: What did you think of the ability of Cho Minsuk as the commissioner?

Pai Hyungmin: I worked with Cho Minsuk at the 2011 Gwangju Design Biennale, where we were both curators. Seung H-Sang and Ai Wei Wei were the directors and I was the senior curator. I formed a relation with Cho Minsuk, not as a critic of his work, but as co-members of a curatorial team. From that experience, I knew he was someone I could work with in the future. So when he proposed a collaboration in 2014, I said OK. Cho Minsuk is an excellent exhibition designer and curator. I personally think he is one of the few architects in Korea with the mindset of a curator. Architects are not curators. They can come up with a big theme but few know how to curate an exhibition. Cho Minsuk did a great job of putting together a team. He played the role of both curator and commissioner. He invited me and Ahn Changmo (professor, Kyonggi University), both older than him, to be curators. It might be a bit overwhelming to try to control the entire exhibition but he was open-minded.

Bang Yukyung: When you worked together, what kind of task in specific did you start with? Pai Hyungmin: I was asked to be a curator but I didn’t know much about North Korean architecture. It was difficult because no one in the planning team had been to North Korea. The possibility of making direct contact with North Korean officials in Beijing through Pyongyang University of Science and Technology (North Korea’s first private university) was briefly pursued. But looking back, I think it was impossible under the Park Geun-hye regime. Hence, international participants and someone like Yim Dongwoo (professor, Hongik University), a Canadian citizen, or (...)

_

1 There was an invited exhibition of Seung H-Sang, entitled ‘Culturescape: Works in Korean Modernity’, held at the Aedes Gallery in Berlin, Germany from 23 Sep. to 3 Nov. 2005. According to the previous interview with Seung H-Sang, he was originally invited to have a solo exhibition. However, the final arrangement was to have two exhibition rooms, one introducing Seung H-Sang’s own work and the other introducing the work of Korean architects built in Paju Bookcity through panels and models. The exhibition opening was attended by Florian Beigel, Joh Sungyong and members of the Korea Culture and Arts Foundation (currently Arts Council Korea). Photos of the event can be found in the online archive of the Aedes Gallery. https://www.aedes-arc.de/cms/aedes/de/ programm?id=19037536

2 ‘Kim Jongshin: Not long after I returned to Korea from studying in the U.K. in 2007, a friend asked me to film some interviews. I went there without knowing who the interviewer and interviewee were, and found myself at the scene where Pai Hyungmin, a professor at University of Seoul, was interviewing Yi Ki-ung, the chairman of Youlhwadang. I went there just as a part-time photographer, but it was so much fun. And on the way back in the car with professor Pai Hyungmin, I told him that ‘I did an MA in Screen Drama Direction at Goldsmiths College, U.K., and my wife studied Architecture and the Moving Image at the department of architecture, University of Cambridge, U.K.’ Then he told me he was working on a video to be exhibited at the Venice Biennale, and asked if I would like to work with him. That is how director Jung Dawoon came along. At that time, I didn’t know anything about architecture. Back then, we could never have imagined that, 15 years later, we would be making a documentary about Paju Bookcity.’ Excerpt from an interview published in VMSPACE, online magazine of SPACE. Source: Oh Juyeon, Kim Jongshin and Jung Dawoon, ‘Giraffe Pictures on Documenting the Life of a City: ‘Great Contract: Paju, Book, City’,’ VMSPACE, https://vmspace. com/report/report_view.html?base_seq=MjE0MA, Accessed 17 Dec. 2024.

3 The following book was published by Kimoondang Publishing in Mar. 2010 under the title of Paju Bookcity Culturescape in both Korean and English. This book, with Seung H-Sang listed as the editor, does not contain a separate collection of content related to the Biennale, such as an article on the theme of the exhibition. The first half of the book contains an introduction by Yi Ki-ung (chairman, Youlhwadang), an article by Seung H-Sang (‘Paju Bookcity and People Who Created Its Cultural Landscape’), and an article by Florian Beigel and Philip Christou (‘Paju Landscape Script’), along with the ‘Architectural and design guidelines for Paju Bookcity’. Out of a total of 470 pages, 370 pages are devoted to materials that include overviews, drawings, and photographs of buildings by type, and the second half of the book includes a critique by Pai Hyungmin, ‘The Unfamiliar Boundaries of Paju Bookcity’. This article includes the full text of the ‘Great Contract’, an informal and symbolic agreement between the publishing cooperative and the architects.

4 ‘Seungduk Kim was the commissioner, and Kimsooja was the selected artist. Both Kim’s left South Korea early in their careers, worked in the United States and France, and were perceptive of changes in the international art scene. Within the special circumstances of the Venice Biennale, anthropological and literary concepts were effectively and successfully introduced into the indoor architectural setting of the Korean Pavilion. With To Breathe: Bottari as the title of the exhibition, the architecture of the Korean Pavilion was approached as a bottari (a traditional wrapping cloth), wrapping the outer wall— the boundary between the outdoor and indoor. The bottari concept had been a regular theme for Kimsooja over three decades, and for the biennale, she used a seemingly immaterial material to expand the notion to cover the entire structure. The architecture of the Korean Pavilion was presented as-is, while the translucent film wrapped over the outer surface as a conceptual bottari offered a curious and constantly changing prismatic experience. While visitors experienced refracted and changing light, the inner space of the Korean Pavilion was filled with The Weaving Factory 2004 – 2013, a sound performance featuring the breathing of the artist herself. Meanwhile, To Breathe: Blackout created an encounter completely devoid of light and sound— an increasingly rare experience for the modern city-dwellers. The deprivation encourages thoughts on the most primitive of subjects, not least mortality. Due to space constraints, the deprivation chamber could only allow 1 – 3 entrants for 1 – 2 minutes at a time. By introducing visitors to the emptiness of space, the space itself functioned as art. Full, yet empty, boundlessly expanding inwards and outwards, not as an individual work but as the entirety of the space itself, visitors had to personally experience this piece.’ Excerpt from the exhibition brief for the To Breathe: Bottari, the Korean Pavilion at the International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale 2013. Source: Ho Kyoung-yun, ed., ‘X – 2013’, The Last Pavilion, Arts Council Korea, 2024, pp. 225 – 226.