SPACE March 2025 (No. 688)

I AM AN ARCHITECT

‘I am an Architect’ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

interview Chae Ahram, Yoon Zoosun Team UDTT × Kim Bokyoung

Studio UDTT + UDTT Lab. = Team UDTT

Kim Bokyoung (Kim): Thank you for the warm welcome! To start, please enlighten us as to how Studio UDTT began.

Chae Ahram (Chae): To put it briefly, it all began when I moved to Daejeon, with no connections, on the 1st of February, 2023, and founded Studio UDTT. Prior to that I had been working alongside Dr. Yoon Zoosun at the Architecture & Urban Research Institute (auri) for approximately 2.5 years on projects aimed at creating vibrant neighbourhoods and revitalising local areas.

Yoon Zoosun (Yoon): I first met Chae as part of the Gunsan Community Hall regeneration project, for which I had been put in charge. At the time, the three of us who were working on the project together planned to start a business and continue our collaboration after the completion of this project. However, one team member went on to enrol in a Ph.D. programme, and I was accepted for a faculty position – the first I had ever applied for – so Chae ended up starting the company alone. We still collaborate under the name, Team UDTT. I co-plan projects through the UDTT Lab., a research lab at Chungnam National University, as an advisor. Chae also plays an active role in field workshops for my classes.

Kim: I am also curious about what led each of you to take an interest in regional revitalisation projects.

Chae: I followed a pretty conventional path in studying the fine arts. But I was always interested in places. My curiosity focused on topics such as how people shape spaces and build narratives within them, and the public nature of old and historic places. Over time, this interest naturally grew into a desire to be more physically involved in making change, real tangible change, on the frontline of such social concerns. Eventually, I found myself drawn to the fields of local regeneration or urban design.

Yoon: Back in my undergraduate years, I had been so dedicated to design because I wanted to create fun, vibrant neighbourhoods, and I thought being good at design was the key to making that happen. However, even though I had proven my skills by winning the competition, our winning project just seemed uninteresting to me. It was then that I decided to explore a different approach. It was in my first year of the masters when I met Min Hyunsik, Chung Guyon, Joh Sungyong as team tutors at the Seoul School of Architecture (sa). They made us interview people in Suncheon from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., everyday for a week. They emphasised that understanding a city is not about data or history but about understanding the story of its people. In the last three weeks, we began developing our designs based on the stories we gathered, and it was incredibly fun. I felt like we had truly understood the city, and that realisation was so rewarding. From that moment, even though I wasn’t exactly sure what it was, I knew this was what I had been waiting for. So, I wrote my thesis on the making of a viliage, and I believe it was the first thesis in Korean architecture academia to explicitly carry the title of ‘Maulmandulgi (creating a viliage)’.

Chae Ahram

Yoon Zoosun

Making Together, Udangtangtang

Kim: For Team UDTT, there is a guiding concept of DIT (Do It Together). What exactly is this concept?

Chae: DIT adds the concept of collaboration to DIY (Do It Yourself), creating a participatory construction approach whereby multiple people work together to shape local spaces and communities. In DIT, various stakeholders – including space operators with a vision for their space, non-experts interested in DIY, and even public officials, depending on the nature of the space – collaborate with professionals to bring a space to life.

Yoon: During my studies toward a PhD in Japan, I encountered many cases of local regeneration projects that were led by small teams under the concept of DIY renovation. In my attempts to adapt these activities and implement them within the current situation in Korea, I proposed the concept of DIT in the report DIT (Do It Together) Urbanism 101 published by auri in 2019. With the involvement of various stakeholders in the building renovation process, DIT fosters a strong attachment between these stakeholders within the community, while also forging bonds between space operators and local residents. Moreover, residents who acquire construction skills can maintain and manage the space themselves, potentially leading to further repairs and renovations, ultimately contributing to the overall revitalisation of the village. The first DIT workshop was held in December of that year. At the time, no one was familiar with this concept, and even the carpenters we recruited were against it. They argued that it wouldn’t make sense to pay money to fix someone else’s house when even young professionals who are paid for this kind of work find it exhausting and quit. (laugh) But I had confidence. In the end, we had a competitive application ratio of 2.5 to 1—a success. These activities have continued as part of Team UDTT’s work ever since.

Kim: To lead a DIT workshop, it seems like there’s a lot to manage beyond just planning.

Chae: DIT is a highly collaborative site in which various people work closely together and therefore requires a lot of detailed coordination in advance. Although the workshop itself is quite short, we usually spend a month or two on preparation. This stage involves a lot of discussion. The goal is to ensure that participants not only have a fulfilling experience in shaping their community but also gain a deeper understanding of their surrounding neighbourhood. The process begins with collectively shaping a design that aligns with the needs of the space’s owner or operator. Once a design is established, we need to set construction tasks that match the skill levels of participants. We also work on creating the right atmosphere for each workshop, from promotion to on-site execution. For example, all workshops start with the distribution of nametags to encourage everyone to address each other by their names on equal terms. Creating an environment of equality helps ensure that learning happens in a safe space and allows each participant to contribute their own particular strengths. This is why we invest time and energy into finding skilled construction professionals who are also excellent communicators.

Kim: The idea of safely and joyfully creating a space sounds amazing—I’d love to participate someday.

Chae: Anytime. We will keep our doors open! (laugh) Learning how to build a space and make furniture is fascinating and fun in itself, but the real charm of DIT lies in that moment when you suddenly sit back and stretch your back and look around—only to see everyone else working alongside you. Working together, you see what your strengths are and recognise the strengths of others. Through DIT, people develop a sense of attachment to a space because they built it themselves, and friendships naturally form between those working together. And this space now becomes a meaningful place where these people want to come back as visitors, wondering how others who participated in this project are doing. Looking at these relationships is what motivates us to keep DIT running.

Kim: Do you think DIT has an impact on regional revitalisation?

Chae: Some people have found DIT so enjoyable that they’ve even relocated to Daejeon to be part of it. More recently, I’ve noticed an increase in property owners who, inspired by our activities, want to try something similar in their own communities. It is also fascinating to see those in the project team, such as our carpenters and planners with whom we work closely, be influenced by the project. Craftsmen, who previously identified themselves as labourers working to tight deadlines, gain newfound confidence and vision as skilled professionals through the DIT workshops. Some even become DIT organisers themselves because they find the process so enjoyable. Everyday I witness just how many different people can become involved in shaping spaces in various ways—all it takes is the right spark.

Interior view of Studio UDTT

Scene from the DIT workshop for the Gangneung Noam Tunnel in October 2024. In a tunnel abandoned after the railway went underground, a 15-member of elder resident community from Noam-dong, Gangneung spent a day making carts for use at neighbourhood events. ©Studio UDTT & UDTT Lab., department of architecuture at Chungnam National University

Scene from the Daejeon DIT workshop in August 2023. 15 people - musicians, fans, and neighbours - came together for two days to build a stage in a complex cultural space in Daesae-dong, Jung-gu, Daejeon. A small performance was held on the newly built stage. ©Studio UDTT & UDTT Lab., department of architecuture at Chungnam National University

The Era of the Makers

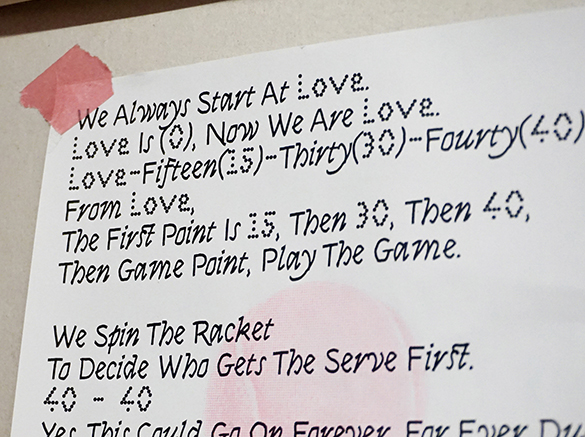

Kim: The note in gyo.musil (a bar in the Studio UDTT) is quite impressive. It said, ‘tal (means escape in Korean)- architecture = neighbourhood architect’.

Yoon: The ‘tal’ of tal-architecture is used to mean ‘expansion’ rather than ‘escape’. In fact, the concept of an architect as a profession in which a practitioner draws blueprints has only been around for about 200 years. Prior to that, carpenters, monks, painters, and sculptors built houses, cathedrals, and public buildings. With modernisation and the need for mass construction, division of labour led to the birth of architects. But we are no longer in an era in which we need to mass-produce buildings. Rather, in regional cities, the number of vacant buildings are on the increase. However, most architecture schools in Korea still focus solely on industrial-era architecture. The scope of architecture itself needs to expand to include hands-on craftsmanship like woodworking, as well as planning and operation. If we define architecture in this broader sense, then not only Ahram and myself but anyone participating in DIT could be considered ‘neighborhood architects’.

Chae: The title architect has always felt too heavy and demanding for me. If we can expand its definition to include those who create spaces and more importantly, those who build and organise places, then I think I, too, could be considered an architect. (laugh)

Through DIT and the act of place making, meeting people from various backgrounds and witnessing in person how a place is made through construction, I realised that ‘there is no single answer to creating a space.’ There were more aspects than I expected that feature in my own decisions. Of course, in new construction projects or large-scale renovations, there are well-established systems in place for safety and engineering. But in that sense, I have learned that the people involved in shaping spaces don’t necessarily have to be limited to professional groups. Most recently my thoughts have been dominated by the question, ‘Can any curious mind take part in building spaces?’

Yoon: We were all once makers of food, clothing, and buildings, until we became consumers who simply buy what others have made. Now it certainly feels like we are entering an era in which people are returning to being makers again; whether it’s food, clothing, homes, or even alcohol. (laugh)

Kim: As a maker, what are your hopes for the future?

Yoon: I’ve tried expanding the scope of architecture by running more hands-on seasonal courses and experimenting with new design studio curricula. However, most students still think, ‘That was fun, but it’s not what I hope to do in my profession,’ and end up aiming for traditional architecture firms after graduation. It would be great if we could branch out more. Specifically, I hope that at least 10% of our graduates will settle in Daejeon as ‘entrepreneurial architects’ or ‘carpenter-architects’. Many students at Chungnam National University are originally from Daejeon, yet after graduation, almost all move to architectural firms in Seoul. I often question whether if that’s truly the right path. It is frustrating to see talented individuals, who have strong local networks and a deep understanding of their hometown, departing for urban centres. Although the difficulty of making a living solely off of design is understandable, I believe that it can be made possible through a more diversified approach—by running a business, doing carpentry, interior design, or even graphic design. Just like the architects of the Renaissance era.

Chae: At first, I thought that the role of design was simply to create decent spaces. But through these activities, I’ve come to realise that making a good space is actually about nurturing it. Of course, creating something is important, but caring for it – cleaning, maintaining, and looking after it – is what truly fosters a sense of attachment to a space. In the end, it’s the people who cherish a space that make it a good and inviting place. DIT shows people how to love their spaces, no matter the neighbourhood or the size of the project. And I want to keep doing this kind of work.

If I were to think of a near-future goal, it would be to establish a space of our own—one that we can sustain over a long period of time. Up until now, we’ve been working on other people’s spaces, contributing only to a small part of a much longer timeline in different places. I think it would be great to have a space where we can observe the evolving impact of DIT over time. After completing a space, we could build a crew to run it. Wouldn’t that be an amazing next step? (laugh)

Chae Ahram and Yoon Zoosun, our interviewees, want to be shared some stories from Kim Hyebin, Ha Jingu (co-principals, Kong and Ha) in April 2025 issue.