SPACE August 2025 (No. 693)

I AM AN ARCHITECT

‘I am an Architect’ was planned to meet young architects who seek their own architecture in a variety of materials and methods. What do they like, explore, and worry about? SPACE is going to discover individual characteristics of them rather than group them into a single category. The relay interview continues when the architect who participated in the conversation calls another architect in the next turn.

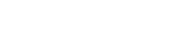

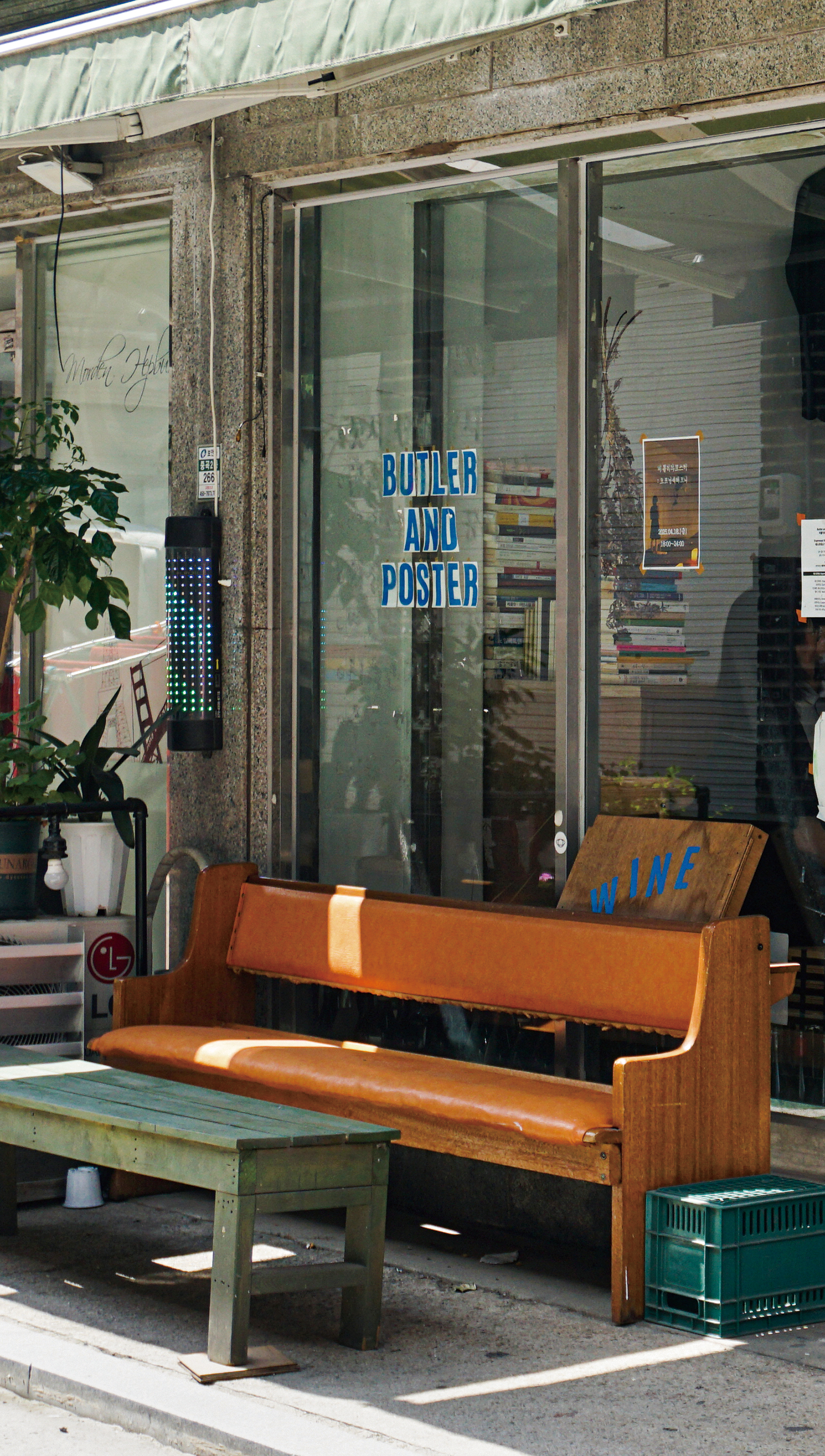

Butler and Poster: Knight lands (2023) ©Choi Yeonkeun

interview Son Minsun, Cho Hyeongjun co-principals, artist duo Mu:p × Kim Hyerin

A Platform Beyond Form: Mu:p

Kim Hyerin (Kim): Since 2013, the architect Son Minsun and choreographer Cho Hyeongjun have collaborated as the artist duo Mu:p (hereinafter Mu:p), exploring the relationship between movement and space. Could you tell us how Mu:p first came into being?

Cho Hyeongjun (Cho): After graduating from university and working as a dancer, I had the opportunity to participate as a choreographer in a project titled Theatre, Inside Out (2013), which explored the intersections between the body and architecture. At the time, I knew very little about architecture, so I turned to Son, who was then my girlfriend, and began asking her various questions. That led us to start collaborating on the piece. The idea of connecting spatial design with physical movement was genuinely fascinating. Even as a dancer, I’d always been interested in systems, the way we perceive space, and trajectories. When I began translating spatial qualities into choreographic language, it felt as though new pathways opened up, and, suddenly, the scope of what was possible expanded tremendously.

Son Minsun (Son): At the outset, we were often at sea, as neither of us was particularly familiar with the other’s discipline. Since we were creating a performance together, we needed to exchange views on architecture and dance. Initially, there were certainly moments of friction, of feeling that something wasn’t quite working. But as the project came together in time for the performance deadline, the work itself became enjoyable. From that point on, we began submitting proposals for various grants under the name Mu:p.

Kim: The name ‘Mu:p’ is quite unusual. What does it mean?

Son: ‘Mu:p (뭎)’ is the word for ‘form (폼)’ written in Hangul, turned upside down.

Cho: We wanted to move away from pretension and instead bring together the things we found meaningful—ideas that connected us or had a methodological quality. The name was conceived as a gesture towards inverting ‘form’, yet ironically, it was so unconventional that it caused issues—setting up a bank account took far longer than expected! In newspaper articles, it would often appear as question marks or even as ‘×’. (laugh) At one point, we did wonder if we’d chosen the wrong name, but in the end, it felt like an apt reflection of our identity.

Son: That’s when we began using the Romanised version, Mu:p. Later, we created a theatre-tour format performance under the name Mu:p Travel, and when I qualified as a licensed architect, I named my firm Mu:p Architects.

Kim: How do you distinguish between the activities of Mu:p and those of Mu:p Travel?

Cho: In truth, they’re essentially the same, it’s just that we apply different filters. For each project, we carefully consider the role we should assume. Much like role-playing, people perform different versions of themselves depending on the space or community they find themselves in.

Son: For instance, when we were making the educational programme, we referred to ourselves as Mu:p Education. In that sense, Mu:p functions as a platform—a locus that can continually shift in form or methodology. Ideally, we want it to remain something mutable, a site or framework open to transformation.

Son Minsun (left) and Cho Hyeongjun (right)

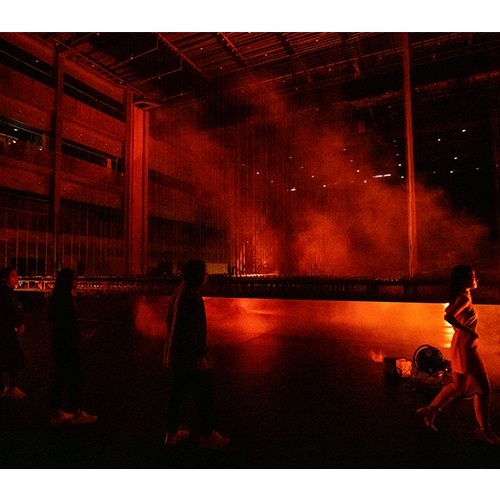

The performance cue sheet

Connecting Space and Gestures

Kim: Within Mu:p, how do your respective roles manifest?

Son: Conventionally, people may think I would design the space, and Cho would choreograph the movement. However, our process is far more porous: we leave all aspects open to discussion, engaging in a continual ping‑pong dialogue to broaden our conceptual boundaries.

Kim: The vocabulary of movement adopted by Mu:p departs from that used in conventional modern dance—it’s highly distinctive. What underpins your choreographic choices?

Cho: We came to feel that, in order for movement within a performance to carry the kind of meaning we seek in our work, it must not take the form of conventional dance. After all, few people are able to discern any precise meaning from the gestures of contemporary dance. In contrast, performative movements – rather than stylised choreography – tend to generate more precise perceptual meanings and create context more readily. Actions such as running, colliding, or falling, for instance, are intuitively legible and therefore offer a more direct register of interpretation.

Son: That said, dance gestures remain one of the many compositional elements we occasionally employ in our performances. When we regard movement as a kind of score▼1, actions such as running, falling, colliding, pushing, or carrying all become part of that score. In the same way, dance too is treated as a score, introduced selectively and positioned within specific spatial contexts when required.

Kim: What methods do you employ to integrate architecture with choreography?

Cho: Each of our works differ considerably in approach. In our earlier pieces, we often analysed movement as patterns, combining paths and gestures algorithmically, or rendering them diagrammatically. From the middle of our practice onwards, we began to examine what kinds of movement might emerge when the choreography directly responds to the physical characteristics of a given space. We also consider how existing architectural elements might be reconfigured as part of the performance. A case in point would be Cascade Passage (2020, 2023), a piece constructed around the movement of the theatre itself. In that piece, the theatre moved and people toured it, rather than dancers performing. We interpret the physical movement of objects as dance, and likewise, the audience’s movement as choreographic material.

Son: A performance comprises temporal flow, light, stage or installation, human movement, and, crucially, the presence of the audience. We tend to regard choreography as the orchestration of these elements as they shift or transform within a shared temporal frame. In this sense, our concern lies with how various layers of all the objects move in relation to one another through time, and how such movement might allow space to be perceived differently from how it is ordinarily experienced. We aim to create conditions in which these layered dynamics can be sensually apprehended. This orchestration is precisely what we call ‘choreography’.

Cho: Indeed, that is reminiscent of architectural practice: considering how light migrates within a space, and planning minute spatial configurations to sculpt sensory experience.

Kim: You prepare performance cue sheets in a similar manner to the drawing up of architectural plans.

Son: Yes; a timeline, cue sheet or score, though we call it by a different name each time. (laugh) We’ve imported architectural conventions, such as using CAD to draft what is essentially a plan with added temporality. Early on, we used tracing paper to flatten the space, mapping performer positions and circulation. Visualising pathways through a plan allows more precise spatial relationships than purely mental or embodied rehearsal.

Café & wine bar Butler and Poster. The title of the performance, Butler and Poster, refers to character names symbolising Cho Hyeongjun and Son Minsun, respectively. These characters represent two of the seven human archetypes proposed in the educational programme Forest 1.4 (2024).

Works Beyond the Work

Kim: A Blast Furnace for Initiation (2023) impressed me in the way how it invited the audience to experience the performance’s routes directly. It feels quintessentially Mu:p to draw viewers into the piece.

Cho: We never begin in a conventional proscenium theatre. Instead, we start in spaces like building lobbies where the audience is already mingling, or in occupied places. Each time, performances unfold uniquely according to the spatial conditions, not in a fixed, predictable format. We favour fluid engagement with our audiences and deliberately incorporate these audience variables into our creative simulations.

Kim: What devices do you use to integrate the audience into a performance?

Son, Cho: we experiment with new modes of entry. Whereas theatre has prescribed ingress, we propose varied portal experiences into our site‑specific time – space. For Butler and Poster: Knight lands (2023), for instance, we chose a venue with ten glass façade doors opening into an external grove. Rather than using the theatre’s main entrance, we guided audiences into the building through a series of exterior doors, of which only one, selected at random from a set of ten, was left open. Ushers remained unaware of which door, adding to the unpredictability of the situation. Audiences rode a nine‑person lift in staggered waves. In some moments, performers broke through walls after holding the audience in narrow corridors between walls until tension peaked.

Kim: You also operate the site Stage after Work or Death (2024 –), which archives both audience-experienced and non‑experienced performances. How did that come about?

Cho: The writings published in Stage after Work or Death stem from our ongoing inquiry into how performances are remembered, or, more precisely, how what has already passed might be recalled or archived within memory. The act of reflecting on a performance after it has ended is not unlike the way one remembers the dead. No matter how many photos or videos we capture, or summon them from our memory, these are only a residue of what has already passed, not an exact recreation.

Son: Unlike other art forms, a performance has a set duration. If one happens to miss a performance due to other commitments, any account gathered afterwards will inevitably differ from person to person. Recording always reflects the recorder’s perspective. It emerged out of this question: ‘How, then, are we to preserve a stage that disappears?’ From this, we began to assemble our group of contributors. Some of them had witnessed the performance firsthand, while others had not. Those who haven’t seen the show might guess from photos or videos, or they might hear about it from us. They write articles, and we give back to them with some of the transcripts from past shows.

Installation view of A Blast Furnace for Initiation (2023) ©Choi Yeonkeun

Cascade Passage (2020) ©National Asian Culture Center

Building, Reflecting, Practising

Kim: Son opened Mu:p Architects in 2021, after focusing on making artworks for a time. What led to that decision?

Son: Though I was involved in architecture, my work shifted toward performance. After leaving my job, I worked on architectural projects on a freelance basis. While working at a firm, I was largely confined to partial tasks, but after leaving, I was unexpectedly given the opportunity to design entire buildings. Naturally, I sat my architect’s licence and opened the practice.

Kim: You span multiple fields – architecture, performance, and artmaking. How do you maintain balance?

Son: I’m busy, yet not overly so. That’s partly why I opened Butler and Poster – this very space we’re in now. (laugh) I think the main reason I’m able to do this is because I don’t have a commute. As a one‑person firm, I can allocate my time freely and work at all hours.

Kim: Tell me about Butler and Poster. What kind of space is it?

Son: It’s a café and wine bar that we run, and I spend the majority of my time here. Although Mu:p Architects is nearby, we draft architectural work here and conceive Mu:p performances in this space.

Cho: We deliberately left the interior largely untouched. As we are deeply concerned about environmental issues, we have chosen not to purchase or produce anything new. Instead, the space was furnished entirely with items we already owned or acquired second-hand.

Kim: What themes are capturing your interest at present?

Cho: Lately, I’ve been drawn to flat things—paper, two‑dimensional paintings, text. Even flat objects contain built space within them, and therein lie vast temporalities. I sense there’s something to explore in that.

Son: I’m preparing the National Children’s Museum of Korea’s 2025 Summer Vacation Education Program, Fence, Family, and Beyond. We’re considering how performance‑oriented architecture and movement can positively impact children. With so many programmes aimed at young audiences, I’m asking: ‘What new insights might children derive from combining architectural practice with movement?’ Our children are growing up, too, which prompts me to consider how we might activate these points of positive stimulus.

Son Minsun and Cho Hyeongjun, our interviewees, want to be shared some stories from Kim Wonill (principal, Becban Architecture) in September 2025 issue.

1 (In dance) a unit of rules or instructions set by a choreographer to structure or guide movement.

Son Minsun and Cho Hyeongjun